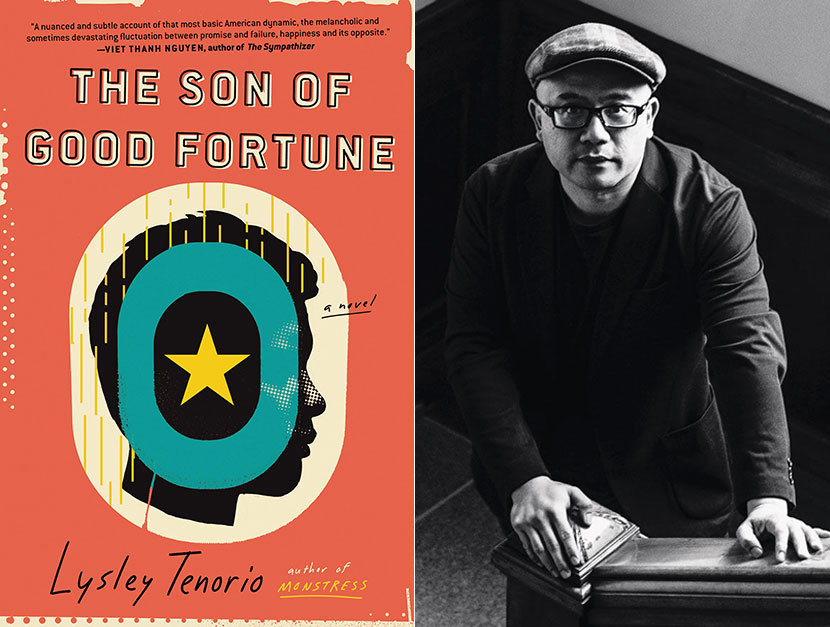

Our latest guest blog post by a contemporary writer comes from Lysley Tenorio, whose debut novel The Son of Good Fortune has just been published by Ecco.

The titular Son of Tenorio’s novel is Excel, an undocumented Filipino teenager holed up in a San Francisco suburb with his mother, a former star of action movies in the Philippines whose own marginal status leads her to begin catfishing a series of American men she meets online. Pathos and comedy intertwine in what USA Today has called “a powerful story about what it takes to uncover a sense of oneself when you’ve been forced to keep it under wraps,” while the San Francisco Chronicle says that in Tenorio’s hands, “The line between the exploited and the exploiter blurs in fascinating and uncomfortable ways.”

Below, Tenorio offers a uniquely personal tribute to a pre-eminent chronicler of the American immigrant experience.

By Lysley Tenorio

I wrote my novel, The Son of Good Fortune, in many places far from home: Manhattan, New Hampshire, Upstate New York, the Adirondacks, Point Reyes, Oxford, Italy. Given all my packing and unpacking, I had to accept that books just don’t travel well, and trust that wherever I landed, I’d find something good to read.

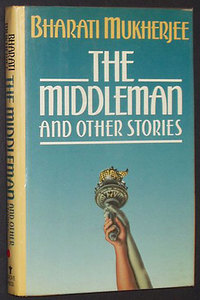

But I never left home without The Middleman and Other Stories. I crammed the book, a hardcover first edition signed by the author, Bharati Mukherjee, into the most overstuffed bag, no matter where I went.

Published in 1988, The Middleman is a collection of stories about immigrant America, and the range of narrators, voices, and subjects is staggering. “A Wife’s Story” centers on Panna, a Columbia graduate student from India, forced to play Manhattan tour guide to her visiting husband. “Loose Ends” is narrated by a white Vietnam vet who becomes a jaded killer-for-hire; “Jasmine” is told by an undocumented Trinidadian woman working as a housekeeper for married professors. Some stories build toward big-drama climactic moments (Mukherjee doesn’t shy away from violence); others pulse steadily toward small gestures equally devastating in their own way, leaving lives forever changed. In these stories, America isn’t just a setting for Mukherjee’s characters but an actual encounter, a landscape that simultaneously welcomes and denies, and is constantly made new by its recent arrivals. The idea of an America in flux, with a constantly shifting national identity, might not seem so new in 2020; our culture, our popular culture in particular, is starting—finally—to open more to artists of color from different immigrant backgrounds. But thirty years ago, the America presented in The Middleman was revolutionary, centering the lives of immigrants from Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, the Caribbean, and India. A landmark in American short fiction, the book went on to win the National Book Critics Circle Award, making Mukherjee the first naturalized citizen—and the first Indian-American writer—to receive the prize.

The emotional and dramatic range of these stories have been a vital influence on my own fiction, and a reminder that the American immigrant story is always a story of change, however huge or seemingly miniscule. The Middleman taught me to find this balance, to aim not for a happy or sad ending, but to finish every story with the truth—that every character’s life is a measure of victory against loss and culminating, in that aftermath, in the most human of questions: Where do I go from here? With every story I write, this is the ultimate goal: to give my characters a sense of possibility, even after the final page.

I first read The Middleman in college at UC Berkeley, when I took a literature course with Mukherjee, and the depth and diversity of these stories blew me away. It was also the first time that I encountered a Filipino character in contemporary fiction (Blanquita, from “Fighting for the Rebound”) and seeing her made me realize what I’d been missing in my own reading: the presence of Filipino characters—and Filipino writers—in American fiction. Though there were a few at the time—Jessica Hagedorn, thankfully, was leading the way with Dogeaters—there weren’t nearly enough, and though I didn’t think of myself as someone who might actually contribute to that literary conversation, the stories in The Middleman made me want to try.

As did Mukherjee herself. Though a writer above all else, she didn’t shy away from a political agenda in her work. In a 1997 article for Mother Jones, Mukherjee writes, “. . . my literary agenda begins by acknowledging that America has transformed me. It does not end until I show that I (along with the hundreds of thousands of immigrants like me) am minute by minute transforming America.” Her words have become, for me, a kind of rallying cry, one that energizes my work, and makes the act of creating absolutely necessary: writing fiction is my way of affirming and insisting upon the acknowledgement of the Filipino presence in America. We have been, and will continue to be, an integral part of the American reality.

I wrote part of The Son of Good Fortune in New Hampshire, during the winter of 2017, in a cabin at the MacDowell Colony. It was there that I learned Mukherjee had passed away, just weeks before. Her death hit hard; I couldn’t write for days, just slept and stared out the window, watching snow. And though I’d packed The Middleman, it felt too soon—and too sad—to re-read; I left it on the fireplace mantle instead. One evening, I found our last correspondence from years before, a reply to an e-mail I’d sent her letting her know that my first book, a story collection, was about to be published. “I’m so very proud of your many accomplishments as an American writer,” she wrote. “And I’m thrilled to have been one of many igniting sparks in your compulsion to be a fiction writer.” That wasn’t quite true: Bharati Mukherjee was the igniting spark; The Middleman was what made me want to become a writer and, after I picked it up from the mantle and set it on my desk, was the book that helped me get back to work.

Lysley Tenorio is the author of the novel The Son of Good Fortune and the story collection Monstress, named a book of the year by the San Francisco Chronicle. He is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, a Whiting Award, a Stegner fellowship, and the Rome Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, as well as residencies from the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, and the Bogliasco Foundation. His stories have appeared in The Atlantic, Zoetrope: All-Story, and Ploughshares, and have been adapted for the stage by the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco and the Ma-Yi Theater in New York City. He is a professor at Saint Mary’s College of California.