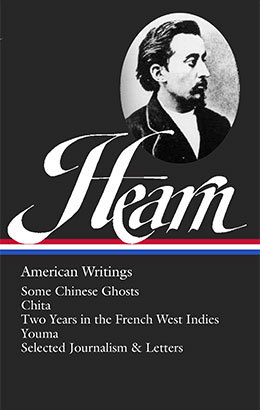

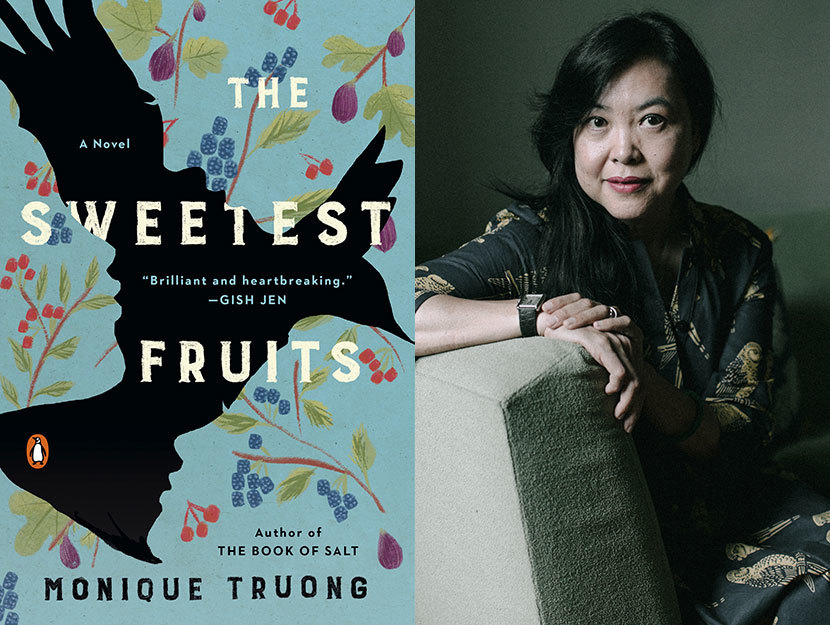

Published in 2019 and just out in paperback from Penguin Books, Monique Truong’s novel The Sweetest Fruits is a vivid fictional imagining of the life of Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904)—the peripatetic half-Greek, half-Irish journalist and novelist who made a name for himself in the United States and then in Japan.

Rather than a more straightforward rendering of Hearn’s life and career—the literary equivalent of a biopic, as it were—The Sweetest Fruits gives us a composite portrait, the writer seen through the eyes of his Greek mother, his African American first wife, and his Japanese second wife. Drawing on remarkable powers of empathy and a gift for sensual detail, Truong recreates the diverse milieus (all on different continents) that each woman came from and restores a sense of agency to three remarkable human beings whose significance has too often been overlooked. At the same time, the book humanizes the shape-shifter Hearn and enriches our understanding of his work.

We were especially eager to talk to Truong because The Sweetest Fruits is actually the second time she has approached the life of a writer in the Library of America series from an oblique angle. In her equally recommended 2003 debut novel, The Book of Salt, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas come to life from the perspective of their live-in Vietnamese cook, Binh, whose presence refreshes and enlivens the book’s depiction of high-bohemian Paris between the wars.

Via email, Monique Truong answered our questions about these novels from her home in Brooklyn.

Library of America: Lafcadio Hearn is one of the more elusive figures in American literature, and your novel is centered on three women, all real people, who are (or have been) more elusive still. How did you come to decide that theirs were the stories you wanted to tell?

Monique Truong: It’s interesting that Hearn is considered “elusive,” given his many books and essays, published during his lifetime and posthumously. Not to mention his voluminous correspondence, collected and published within two years of his passing, some of which is included in the LOA’s Lafcadio Hearn: American Writings, and the many biographies devoted to him, yes? By “elusive,” perhaps what is meant is that he’s difficult to define, given his connections, associations, and claimed authority toward multiple countries and cultures? Hearn is “elusive” because he eludes easy categories and descriptors?

It’s this multiplicity within Hearn that suggested to me that a single point of view could not fully explore nor engage with his life story.

His mother Rosa and his wives Alethea and Setsu were each travelers in their own ways. They crossed borders, whether it was the Irish Sea, the Ohio River, or the Inland Sea. To me, their lives were epic, brave, and were truly elusive in that Rosa and Alethea were denied access to the written word—I choose this phrasing purposefully, as “illiterate” doesn’t capture the lack of access to education and only the resulting state of unknowing. These women couldn’t leave behind a record of their thoughts and experiences. Everything we know about them is secondhand. Setsu was less elusive, as she wrote a brief memoir, Reminiscences of Lafcadio Hearn, which offers us a glimpse of her being as well as Hearn’s.

LOA: Hearn presents a complicated case: The prototypical transnational writer, he was undeniably prone to exoticizing and his work raises questions around cultural appropriation. On the other hand, to speak only of his U.S. phase, Deborah Baker has written on our website that “he yet saw clearly those aspects of American life that passed unseen by Gilded Age literary sensibilities, eager for London’s attention.” Comment?

Truong: Hearn’s article “Saint Malo: A Lacustrine Village in Louisiana” in the March 31, 1883, issue of Harper’s Weekly is a good example of when his attraction to the obscure and the “exotic” lead him to the “Orient at home,” as Baker noted on the LOA website.

In this instance, Hearn found the Orient one hundred miles from New Orleans in a small, isolated village of “Malay” fishermen. According to subsequent researchers, these men, more likely, had roots in the Philippines. Nonetheless, thanks to Hearn, we now have a kind of literary census of this community of “cinnamon-colored men.” Hearn chronicles their first names, sometimes their ages, and for a few he even provides a partial family history. In a characteristic Hearnian gesture, he also includes a rather detailed listing of the way that numbers are called out during their card games. The number 22 is “two ducklings,” 33 is “the age of Christ,” and so on. It’s an invaluable glimpse into these men’s imagination and the metaphorical and visual imageries that they share. It’s a rare writer of his era who recognizes not only the exterior but also the interior lives of the “exotic.”

LOA: The hardcover release of The Sweetest Fruits in 2019 happened to coincide with the publication of not one but two new editions of Hearn’s Japanese folk tales. How does your novel inform or enlarge our reading of those stories?

Truong: Setsu’s memoir wasn’t her only narrative act. She was also Hearn’s literary collaborator. She told him many of the folk tales and ghost stories that he then rewrote in English. Hearn and then his biographers obscured this fact. With rare exceptions, the biographers insisted on focusing on Setsu’s “illiteracy” in English, while ignoring that she could read and write in Japanese. They also skipped lightly over the fact that Hearn had minimal knowledge of Japanese and relied upon Setsu as well as others to translate for him during his fourteen years in Japan.

The biographers also claimed that Hearn devised a private language, consisting of simple English and Japanese words, so that he could converse with Setsu. These biographers must have never been in a domestic or romantic relationship, because otherwise they would have been more clear-eyed and credited Setsu with the co-creation of this language. Perhaps they thought of Hearn as the writer and therefore the sole “creator,” and Setsu as an “illiterate” woman and therefore merely able to parrot said language?

My novel doesn’t assume an impoverished, one-sided relationship between Hearn and Setsu. Building upon her memoir and scholarly sources from Japan, The Sweetest Fruits imagines the inception of their private language and which words are necessary to build a linguistic bridge. Also, the novel imagines how Setsu’s telling, reliant upon a vocabularic scarcity, must distill a story down to its essence, and how that distillation can then shape and enhance Hearn’s understanding of these folk tales and ghost stories. The resulting narratives are collaborative, neither Japanese nor Western, and in these ways are as emblematic of a changing Meiji Japan as they are of the “unfamiliar,” traditional Japan, which Hearn thought that he was presenting to his readers.

| LOA eBOOK CLASSIC |

|

| Lafcadio Hearn: Some Chinese Ghosts |

LOA: In an interview with Mochi last fall you suggested that The Sweetest Fruits can be read as “a Vietnamese refugee narrative, but with no Vietnamese in it.” At the risk of oversimplifying: Does this novel extend the work you began in The Book of Salt, which has a Vietnamese exile at its center?

Truong: At the core of my three novels is the characters’ search for home, which is not necessarily found on a map but rather is a state of being. For me, that search is very much informed by my experience as a Vietnamese refugee and a Vietnamese American. So, yes, absolutely The Sweetest Fruits is a continuation of the narrative project that I began with The Book of Salt and Bitter in the Mouth. As Hearn’s own life story makes clear, that search is an ongoing one.

Born in Saigon, South Vietnam, Monique Truong came to the U.S. as a refugee in 1975 and now lives in Brooklyn, New York. Her novels are The Sweetest Fruits (2019), Bitter in the Mouth (2010), and The Book of Salt (2003). She is also an essayist and librettist, working in collaboration with the composer Joan La Barbara. A Guggenheim Fellow, U.S.-Japan Creative Artists Fellow in Tokyo, Visiting Writer at the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, and Princeton University’s Hodder Fellow, she was most recently the Sidney Harman Writer-in-Residence at Baruch College in New York City. Truong received her BA in Literature from Yale University and her JD from Columbia Law School.