Today we inaugurate an occasional series of guest contributions on reading during a pandemic with a dispatch from writer, antiquarian book dealer, and all-around friend of LOA Henry Wessells. Readers may remember that we interviewed Wessells in this space two years ago, when he presented an exhibition on science fiction and attendant forms of fantastic literature at The Grolier Club in New York City. (The following post is adapted from a newsletter Wessells sent out from his website The Endless Bookshelf on April 30.)

By Henry Wessells

On March 8, the last night of the New York Antiquarian Book Fair—a cosmopolitan gathering of friends, colleagues, librarians, and collectors—I took part in a Q&A for The Booksellers documentary at a New York City cinema, and went home to Montclair, New Jersey. A planned short break turned almost immediately into local sequestration. During this period of quarantine, some of my friends have written to me of losing appetite for reading. Not me.

I had earlier this year resolved to read a few more titles from William Reese’s Narratives of Personal Experience (Overland Press, 2016), and had just finished H. L. Mencken’s Happy Days (1940) in The Days Trilogy (Expanded Edition) from Library of America. I like Mencken’s portrait of Baltimore as a vibrant city, and the way he found his way into the newspaper business. The recollections of childhood are deftly summoned. Playing “something lively” on the piano at his father’s command, he speaks of his “unwitting service as a bouncer” to drive away bores and unwanted guests.

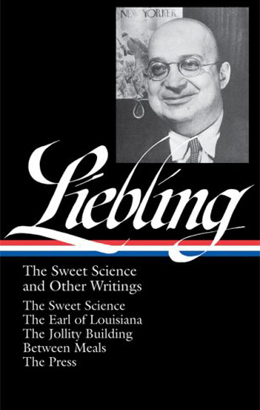

I had also intended to read A. J. Liebling, whom my friend MZ has long been quoting at me. I do not know why I hadn’t listened to him. I picked up Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris (1962), and was immediately seized by the nimble prose and the opportunity to visit an unattainable Paris of the past. I grew up in one (in the middle 1970s), but Liebling writes of the 1920s and 1950s. His world was not that of Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, nor the Paris of Elliot Paul’s madcap detective novels featuring another American expatriate, Homer Evans. Liebling writes of eating as an extreme sport, with the plain speech and scattered diamonds found in his writing about other extreme sports, boxing (which does not seize me) and American politics. The Earl of Louisiana (1961), the book which Reese praises (understandably), is a master class in political chicanery narrated by a writer who “covered the fall of France, the London blitz, American infantry advances across Africa, the Normandy invasion, and the liberation of Paris” (American National Biography), and who can equate the Louisiana patronage machine with the sectarian accommodations of Lebanese politics without missing a beat. Back Where I Came From (1938) and The Telephone Booth Indian (1942) are two delightful anthologies of pieces about New York City. It sometimes seems to me that all the low-life characters in Naked Lunch are refugees from the pages of Liebling freed by William Burroughs into a chronicle of behaviors unlikely to have found favor with Liebling’s editor.

The first half of the headline of this piece is taken from Between Meals and describes my experience during these recent months of reading as connection and communication. I have mostly (well, usually) stayed away from participation in the online fora, and have written or called friends and acquaintances, and read books: “often alone, but seldom lonely.”

I did a fair amount of re-reading, a few of the Judge Dee novels of R. H. van Gulik, and also winding up a persistent effort to re-read the Travis McGee novels of John D. MacDonald. I have only been to Florida twice (more than twenty years ago now), but his books (like Charles Willeford’s Hoke Moseley novels) describe a world of the recent past in brilliant detail and with some surprising insights. MacDonald’s environmentalism is a constant; and also the highly skilled deployment of a friend to shape the narrative delivery of information. We should all be so lucky to have a friend such as Meyer. In these novels, published between 1964 and 1985, one can read a history of America—not the only one, but an acutely observed account of the world. I have read several of the Jack Reacher novels of Lee Child (which my friend JC has read with more rigorous attention than I have). I kept wanting to find an analogous, more recent history of America, but despite hints I see more a pathology. Which may be the point. Reacher is far less closely connected to the world he inhabits than McGee ever was.

“These dreams were not confined to sleep only, and a deplorable side effect was the way I had come to enjoy them.”

—Anna Kavan, Ice (1967). With a foreword by Christopher Priest. Peter Owen Cased Classics no. 4 (2017).

I finally read this novel after multiple, frequent, and persistent recommendations. It is, quite simply, remarkable. It is a novel of the end of the world, not in drought, wind, or flood, but in ice and totalitarianism; and in the mind of a master addict of a novel drug. What struck me as a reader was the experience of a frequently shifting point of view, without transition or explanation of these dislocations from one paragraph to the next. The most striking examples are at pp. 24–25, 50–51, and 84–85 of this edition, with occasional flashes to the end of the book.

Despite the apparent first person narration, the “I” seems to recount third person activities at an objective remove, while sudden passages describing “her” in fact recount a subjective primary experience of “the girl.” The question of the existence of the girl is of course a valid one. Is she the literalization of the drug to which the narrator is addicted? I would be delighted to discuss this with other readers of the novel.

Christopher Brown, Failed State: A Novel (Harper Voyager, forthcoming August 2020).

I read the final copyedited text, courtesy of the author. It is a beautiful, moving book, with fine homegrown American villains (a billionaire dentist and an evil lumberman); a monstrous invention; a bunch of great characters, and well-placed reflections upon the meanings and misuses of past, present, future; and an indictment of the misdeeds of capitalism. Donny Kimoe (whom we met in Brown’s Rule of Capture) becomes someone deeply interesting as he lawyers a path to redemption in a messed-up world. We could all live here together.

Joanne McNeil. Lurking: How a Person Became a User (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020). Lurking is a memoir of experiencing the internet, and thinking about what is going on: gracefully written, with acute observations of the entangled state of human/digital interactions. The degree to which digital communications encode human speech and growth is manifest in her account of the shared vocabularies of teenagers in AOL chatrooms and other now dead media. She is a generation younger than I am, and her perspective is always illuminating.

I met Joanne McNeil thanks to Brendan Byrne, who enlisted me to deliver the keynote address at a Future Fictions gathering at the New School in April 2018 organized by the Virtual Futures collective (the bibliography for Writing the Futures: A Short History can be found here). I will read anything she has written.

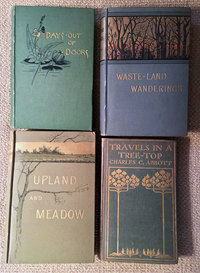

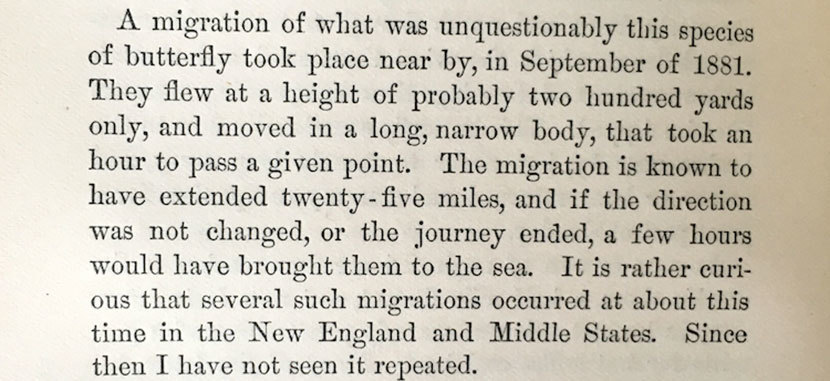

My friend CW suggested I might enjoy reading the works of nineteenth-century New Jersey nature writer and archaeologist Charles Conrad Abbott (1843–1919), a medical graduate who never practiced medicine but instead wrote about the world around his family estate, Three Beeches (south of Trenton). He published The Stone Age in New Jersey in the Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution . . . for the Year 1875 (Government Printing Office, 1876). Abbott was a witness to the disappearance of the nation’s rural character, “but the popularity of his works did not extend far beyond his lifetime” (ANB). In Waste-Land Wanderings (1887), Abbott describes a migration of “milk-weed butterflies,” which we know as the Monarch:

Other works by Abbott which I will read at include: Upland and Meadow. A Poaetquissings Chronicle (1886); Days out of Doors, A Naturalist’s Rambles about Home (1889); and Travels in a Treetop (1894).

Sometimes it is very pleasant to take a walk in the New Jersey woods of the 1880s.