In fall 2000, Library of America published Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Poems & Other Writings, the first comprehensive collection of his work in over twenty-five years. The distinguished poet and critic J. D. McClatchy, the volume’s editor, wrote this piece for The New York Times Book Review at the time of publication. In it, he discusses the Longfellow’s rise to fame, his literary and cultural significance, and the reasons for his enduring popularity. The piece is reprinted here for the enjoyment of our readers.

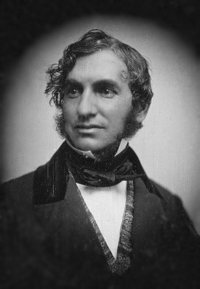

When Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was in England in 1868 to receive an honorary degree from Cambridge University, Queen Victoria invited him to tea. She was a great admirer of his work, and found his company delightful. When she then accompanied the poet to the door, and watched him walk down the long palace corridor, she witnessed something slightly disconcerting. “I noticed,” she confided to her diary that night, “an unusual interest among the attendants and servants. I could scarcely credit that they so generally understood who he was. When he took leave, they concealed themselves in places from which they could get a good look at him as he passed. I have since inquired among them, and am surprised and pleased to find that many of his poems are familiar to them. No other distinguished person has come here that has excited so peculiar an interest.”

Monarch and manservant, coolie and carpetbagger, the whole world read Longfellow. He outsold Browning and Tennyson. In the White House, Lincoln asked to have Longfellow’s poems recited to him, and wept. When the emperor of Brazil made a state visit to America, his only request was to have dinner with the great bard. The poet’s seventieth birthday, in 1877, was a day of national celebration, commemorated by parading schoolchildren around the country. It was proclaimed on that day that “there is no man living for whom there is so universal a feeling of love and gratitude, and no man who ever wore so great a fame so gently and simply.”

His popularity may seem suspicious today, but at the time it was a literary milestone in America. It could be said that Longfellow was our first professional poet. Not only was he able to make a living from his writing but he worked carefully to establish for American poetry a cultural eminence. He was both professor and balladeer. He had literary qualities that rarely coincide and from either sideline are usually sneered at. He had an authority based on learning and allusion, gaining for his work an intellectual respect. And he had a narrative gift both sweeping and canny, along with a near perfect ear, that made his work memorable and gave it an enormous popular appeal.

Longfellow had earned his considerable prestige. From the start, he held himself to the highest literary standards, and was deeply admired by Hawthorne and Emerson, by Dickens and Ruskin. For many years, he taught comparative literature at Harvard, where he introduced Dante, Goethe, and Moliere into the curriculum. He had as well the fabled energies of the Victorian man of letters. Early in his career he traveled widely, mastered eleven languages, and had the entire European literary tradition in his head. He was an indefatigable anthologist (one alone ran to thirty-one volumes), compiler, textbook author, diarist, and correspondent (so besieged was he by admirers that he eventually wrote about 1500 letters a year), and he composed in every genre: novel, romance, and short story; travel sketch, essay, and table-talk; verse play, translation, epic, sonnet, ballad, elegy, and lyric.

Even as a college senior, Longfellow knew what he wanted. In an 1824 letter to his father he wrote, “I most eagerly aspire after future eminence in literature, my whole soul burns most ardently for it, and every earthly thought centres in it.” Had he been merely brilliant, all his learning would not have helped him fulfill that ambition. But he cared too for his readers, for the language of their hearts and memories, and they responded. When The Courtship of Miles Standish and Other Poems appeared in 1858, it sold 25,000 copies in the first two months, and 10,000 copies in London the first day. There was hardly a home in America without its hearthside copy of “Evangeline.” And in the wake of “The Song of Hiawatha,” in 1855, well, the nation is still cluttered with motels and steamboats, summer camps and high schools that bear the name. It was a poem imitated in French by Baudelaire, and translated into Latin by Cardinal Newman’s brother. As “Hiawatha’s Photographing,” it was even quickly parodied by Lewis Carroll. Parody is the last form praise takes; Carroll thought Longfellow “the greatest living master of language,” but his contemporary send-up (“From his shoulder Hiawatha / Took the camera of rosewood, / Made of sliding, folding rosewood; /Neatly put it all together”) takes primitivism into the drawing room with hilarious consequences.

Longfellow himself was no mandarin. He carefully monitored his sales figures and made certain that, in addition to the morocco-bound volumes printed for the carriage trade, there were broadsides and cheap pamphlets available for the common reader. As a result, he was more widely read, more widely appreciated than any American writer of his time. One ironic token of such appreciation is that more of us, even today, can still quote at least the opening of several Longfellow poems, from “I shot an arrow into the air” to “Though the mills of God grind slowly.” In fact, so well known have many of his phrases become they have achieved the dubious status of cliche: “the patter of little feet,” for instance, or “ships that pass in the night” or “into each life some rain must fall.” Here is poem after poem that has sunk into the national consciousness, become an indelible part of the American imagination. How is that possible?

Longfellow lived at a propitious time. He was born in the wake of the Revolutionary War; his grandfather was a colleague of Washington and his father a friend of Lafayette. The great events of the century—the westward expansion, the question of slavery, the Civil War—he had as subjects. And he lived on into the modern extravagances of the Gilded Age; one of his last visitors was Oscar Wilde. His lifetime, in other words, spanned the age when America sought to define itself, and what Longfellow gave his countrymen—who spurned history—was the mythology they needed. Evangeline in the forest primeval, Hiawatha by the shores of Gitche Gumee, the midnight ride of Paul Revere, the wreck of the Hesperus, the village blacksmith under the spreading chestnut tree, the strange courtship of Miles Standish, the maiden Priscilla, and the hesitant John Alden, even the lonely striver’s footprints on the sands of time—together they form a nostalgic image of innocence, a people starting over, a muted but forceful heroism in touch with the rhythms and harmonies of the natural world. Both in his poems and in his undervalued novel Kavanagh, Longfellow creates his Great Good Place. Neither the city nor the wilderness attracts him. Neither the thronged metropolis of Whitman nor the solitary pond of Thoreau draws out his sympathies. Instead, Longfellow feels himself most at home in the village, its dimensions contained, its inhabitants known, its cozy routines established, its eccentric novelties cherished, a civilized community on the edge of the unfamiliar.

At the same time, he boldly helped American poetry welcome European influences, from Germanic legends to Nordic meters, seeking in the term “American” not a thumping, homemade vigor, but a cosmopolitan openness to foreign resources. In his appetite for the unusual, combined with his extraordinary prosodic virtuosity, he seems an unexpected precursor of W. H. Auden, another poet who sought not to defy tradition but to renovate and extend it.

And then, less than half a century after Longfellow’s death, the modernist braves circled and shot him down like a dazed buffalo. Ezra Pound (who was, by the way, Longfellow’s grandnephew) and T. S. Eliot were determined to rid the poetic landscape of mawkishness. Narrative was out, and the skewered, ego-bound lyric was in. Moralizing was out, and psychologizing was in. The elegant and delicate were derided, the fragmented and confessional applauded. Meter and rhyme were considered fustian, and the broken line or free verse effusion was all the rage. Longfellow was officially declared kitsch.

But among the many readers who privately maintained their devotion to the old poet was Robert Frost, in many ways Longfellow’s true successor. The title of Frost’s first book, A Boy’s Will, is taken from a Longfellow poem, and in 1907, to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of Longfellow’s birth, Frost wrote an affectionate poem, “The Later Minstrel,” where he gratefully acknowledges that, while under Longfellow’s spell, “You wronged the wisdom that you had, / And sighed for vanished days.” More cannily than most, Frost understood that “Song’s times and seasons are its own, / Its ways past finding out.” Put aside for a moment your sleek preferences, your ironic prowess, and the minstrel days of old emerge with a remarkable majesty.

Longfellow is not a poet of startling originality, not a Whitman or Dickinson. But he is a much better poet than is now supposed. Yes, he will seem sentimental at times, but from how many Victorian poems would we not nowadays want to snip off the last few, homilizing lines? Still, rereading his best lyrics, one is struck by the twilit, ghostly melancholy of his lost paradises. The moon glides along the damp mysterious chambers of the air, and somber houses are hearsed with plumes of smoke. And the grand narrative poems of his “Tales of a Wayside Inn” sequence have a dramatic thrust and vivid portraiture that can evoke one’s first, enthralled experiences with stories, the high adventurous romance of those books that helped shape our desires and still abide in our memories. If Longfellow has long since been consigned to your dusty top shelf, it may be time to take him down. You won’t just be opening a book. You’ll encounter a world sometimes thought lost, but actually as near as a dream.

Reprinted with permission of J. D. McClatchy.