For the latest edition of Library of America’s new LOA at Home e-newsletter, LOA President and Publisher Max Rudin offered these remarks on William Carlos Williams. The entire article is also available as a streaming, downloadable audio file (.mp3 format) at SoundCloud.

Click here to sign up to receive the LOA e-newsletter.

From Library of America, this is LOA at Home, Issue #2: “A Season of Vulnerability and Hope: Thoughts on William Carlos Williams’s poem ‘Spring and All’.” Here’s the poem:

Spring and All

By William Carlos Williams

By the road to the contagious hospital

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast—a cold wind. Beyond, the

waste of broad, muddy fields

brown with dried weeds, standing and fallen

patches of standing water

the scattering of tall trees

All along the road the reddish

purplish, forked, upstanding, twiggy

stuff of bushes and small trees

with dead, brown leaves under them

leafless vines—

Lifeless in appearance, sluggish

dazed spring approaches—

They enter the new world naked,

cold, uncertain of all

save that they enter. All about them

the cold, familiar wind—

Now the grass, tomorrow

the stiff curl of wildcarrot leafOne by one objects are defined—

It quickens: clarity, outline of leafBut now the stark dignity of

entrance—Still, the profound change

has come upon them: rooted they

grip down and begin to awaken(1923)

I’ve always loved this poem, but until this spring I never felt its full force. The poem captures the inception of spring in a field in New Jersey with photographic precision—both the fragility and the strength of new life pushing up through the twiggy, weedy, stagnant landscape. William Carlos Williams was an obstetrician and pediatrician, and when he observes of the young shoots, “They enter the new world naked . . . uncertain of all save that they enter,” his language makes the connection to another kind of urgent new life.

What never really struck me before now though is the well-known first line: “By the road to the contagious hospital.” This scene of life’s rebirth is taking place along the road to a hospital for infectious disease that the speaker refers to casually as if he’s traveled it often—a hospital that only a few years earlier would have been filled with victims of the 1918 flu pandemic that killed 675,000 Americans. Dr. Williams knew that devastation firsthand, as a family doctor (we’d now call him a “first responder”) treating influenza patients: “They’d be sick one day and gone the next,” he wrote, “just like that, fill up and die.” “We doctors were making up to sixty calls a day. Several of us were knocked out, one of the younger of us died, others caught the thing, and we hadn’t a thing that was effective in checking that potent poison that was sweeping the world.”

|

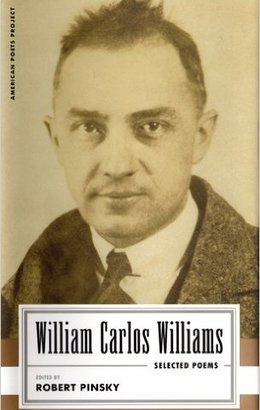

| William Carlos Williams: Selected Poems |

This is the grim world in which new beings must make their way. Its ensign is the cold wind sweeping the field in the poem’s first sentence—the word “cold” appears three times in the poem—a blighting force later invoked, with uncanny horror, as “the cold, familiar wind.” Williams’s poem holds together two nearly incompatible apprehensions: of exhilaration and celebration of the return of life after winter; of danger, and fear, grief and compassion for life’s victims.

I watch daffodils and forsythia bloom outside my window, and the buds of the lilacs and cherry trees begin to swell, and I feel hope. At the same time, I think about friends who are sick, and those we’ve lost, and how vulnerable we all are. This is our world, the world that Dr. Williams was showing us, almost one hundred years ago, in another season of vulnerability and hope.

You’ve been listening to LOA at Home, and this is Max Rudin.

Max Rudin, President & Publisher

Library of America