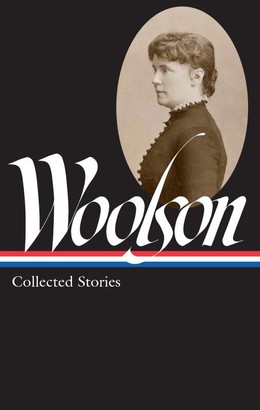

Just out from Library of America, Constance Fenimore Woolson: Collected Stories brings together twenty-one stories by a nineteenth-century writer who in her day was ranked alongside George Eliot as one of the best women fiction writers in the English language

— but whose work fell into unaccountable neglect in the twentieth century.

Whether set in the Great Lakes region, the Reconstruction–era South, or among American expatriates in Europe, these stories display Woolson as an innovator of American literary realism, a writer of deep feeling, psychological complexity, and exceptional descriptive powers.

Representing the culmination of decades of recovery work done by female scholars, Library of America’s new volume is edited by Anne Boyd Rioux, whose 2016 biography Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist has been especially instrumental in restoring and rehabilitating Woolson’s literary reputation.

Rioux is the author of several books in addition to her Woolson biography, including most recently Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters (Norton, 2018). A professor of English at the University of New Orleans, she is the recipient of two National Endowment for the Humanities Awards, one for public scholarship. Via email, she answered our questions about Woolson.

Library of America: Constance Fenimore Woolson: Collected Stories is a large volume of fiction by a writer whom many people don’t know yet. What can newcomers to Woolson look forward to in her work?

Anne Boyd Rioux: Readers can look forward to writing that seems remarkably modern, despite its having been written over a hundred years ago. Woolson participated in the realist movement of her day, drawing her scenes and characters from life. But she challenged some of realism’s tenets, most notably that of the objective observer who only examines the surface of things. Her writings can be compared most fruitfully to George Eliot’s. Woolson’s empathetic realism, like Eliot’s, asks readers to notice people who tend to be overlooked or misunderstood and to understand and feel for those on the margins of society. Yet, also like Eliot, her work was often considered in her own day as quite masculine. In fact, Woolson once wrote that she had “such a horror of ‘pretty,’ ‘sweet’ writing that I should almost prefer a style that was ugly and bitter, provided it was also strong.” The result was a decidedly unsentimental and modern style.

LOA: These twenty-three stories were written over a span of nearly a quarter-century. How does Woolson’s work evolve during that time? In particular, how are the stories written after she left the United States in 1879 different from the “American” ones?

Rioux: By the time she left the U.S. in 1879, never to return, Woolson had established herself as one of America’s most important short story writers. Her stories set in the Great Lakes region and in the Reconstruction South were considered distinctly American and participated in the craze for local color stories, or stories that showed American readers the distinct characters of the wide variety of regions that a reunited nation encompassed. After leaving for Europe, Woolson would continue to set her novels in the U.S., but her short stories were drawn from her life abroad and feature primarily American and British expatriates and travelers in Italy and Switzerland, and, in one story (“In Sloane Street”), London.

Perhaps more significant than the shift in setting, though, is the shift in style. Woolson had begun closely reading Henry James shortly before her move to Europe, and she met him in the spring of 1880, in Florence, initiating a deep friendship that would last until her death in 1894. Although they agreed to destroy their letters to each other (only four of hers to him have survived), we can see in their fiction of these years an ongoing conversation about the nature of art and the roles of women. Woolson could be said to have initiated the conversation with her story “A Florentine Experiment,” which includes many details from their first encounters with each other in Florence and was also a conscious literary experiment on Woolson’s part to try to write in the much-lauded style of James. She wasn’t particularly happy with the results, and she continued to challenge what she saw as his detached analytical realism in her novels and stories, no longer trying to imitate him but maintaining a dialogue that, in my view, carries all the way through James’s “The Beast in the Jungle” (1903), which was clearly influenced not only by their close personal friendship but also their intense artistic dialogue.

LOA: Woolson faded into obscurity for most of the twentieth century. What kind of work is required to restore a long- and unjustly neglected author to the prominence she deserves?

Rioux: First and foremost, it requires rethinking our conceptions of American literary history, particularly the stale but still-predominant view that women writers of the late-nineteenth century were not important players in the mainstream literary movement of the period, namely realism. The practice of relegating women to the literary and cultural margins as local color or regionalist writers, while male writers are lauded as realists, has reified a gender segregation that at the time didn’t really exist. Certainly male writers were still accorded greater respect than women writers, but there were many women—among them Sarah Orne Jewett, Mary Wilkins Freeman, Rebecca Harding Davis, and Harriet Prescott Spofford—who had a significant impact on the mainstream literary discussions of the period, and Woolson was one of the most important.

Woolson also needs to be acknowledged as both a peer and close friend of James’s, not the love-starved spinster and second-rate “magazineish” writer that Leon Edel portrayed her as. The influence has been assumed to go all in one direction (namely from James to Woolson), but her influence on him should be recognized. A lot of important critical work on Woolson has been done that effectively challenges Edel’s demeaning portrait of her in his highly influential five-volume biography of James. What is needed now is a reimagining of their relationship as not only personal but also literary. I hope that my biography of Woolson, in which I attempted to initiate that project, will inspire others to further examine how their friendship affected his writing as well as hers.

LOA: James’s 1887/8 essay on Woolson has been endlessly debated, but one line caught our attention:

She stays at home, and yet gives us a sense of being ‘abroad’; she has a remarkable faculty of making the new world seem ancient.

Is he, in his roundabout Jamesian way, acknowledging Woolson’s gift for rendering remote and even exotic settings in her American stories? (Exotic, that is, to readers of The Atlantic Monthly.) We’d like to hear about the importance of locale in her writing.

Rioux: Yes, but I also think he’s saying that Woolson sought out the “ancient” in America, at a time when most Americans were focused on the present and the future. While her contemporaries were so enthralled with society’s rapid changes, Woolson was intrigued by the Old World communities that had been transplanted to America, like the Zoar community featured in “Solomon” or the Minorcan community in “Miss Elisabetha.” She was also especially drawn to St. Augustine, Florida, called the “Ancient City,” which is the oldest city in America yet has been overlooked, in literature, in favor of the Puritan communities in New England. She grew up in Cleveland, which had become a bustling metropolis during her lifetime, paving over the old at a rapid rate. In response, she was drawn to the colonial remnants she found throughout the South. You might say that Woolson felt it was important to notice the overlooked and marginalized not only among people but also among places.

LOA: Today, as you note in your biography, we would diagnose Woolson as having suffered from clinical depression. Given that, is it misguided to view hers as a tragic story, rather than remarking on everything she did accomplish? (We’re thinking of her prolific literary career and also of her wide-ranging travels—especially her trip through Egypt, which must have been unusual for a single woman in that time and place.)

Rioux: Absolutely! Unfortunately, the two things people remember about Woolson, if they know of her at all, is that she was a friend of Henry James and that she committed suicide in Venice after years of suffering from depression. (Even worse, she is too often assumed—erroneously—to have killed herself out of unrequited love for James.) And if people know her work at all, they tend to know “Miss Grief,” a pretty tragic story that many see as epitomizing not only the neglect of Woolson in favor of male writers like James but the neglect of all women writers of her era.

Yes, she did suffer from depression. And yes, she was often angry at how hard it was for women writers to gain serious recognition. However, we do Woolson a disservice if this is all we remember about her. She also achieved a significant amount of critical and popular success and experienced a great deal of joy in her life. Her life was one of both great struggle (for recognition and enough money to support herself independently) and great courage.