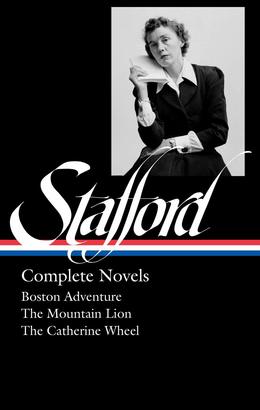

Published late last fall, Library of America’s Jean Stafford: Complete Novels gathers all three novels—Boston Adventure (1944), The Mountain Lion (1947), and The Catherine Wheel (1952)—by the writer whose collected short stories won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1970.

The volume is winning acclaim for its recovery of a major twentieth-century American author. “There is a new opportunity to ask why work of such originality could ever be forgotten,” wrote Parul Sehgal in her New York Times review; “It is not a case of ordinary neglect.” “Jean Stafford’s novels are a revelation for anyone who knows her only from her many short stories,” said Maureen Corrigan in The Wall Street Journal, singling out _Boston Adventure as “one of the most haunting depictions of female isolation in fiction.”

Jean Stafford: Complete Novels is edited by Kathryn Davis, currently the Hurst Writer in Residence at Washington University in St. Louis. The author of eight novels, including Labrador (1988), The Walking Tour (2000), Duplex (2013), and most recently The Silk Road (2019), Davis has received the Katherine Anne Porter Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Lannan Literary Award for Fiction. Via email, she talked to us about Jean Stafford: Complete Novels.

Library of America: One of the first things to be noted about Jean Stafford’s fiction is the variety of her settings. These three novels unfold in three distinct worlds: the North Shore of Massachusetts and the Beacon Hill section of Boston; southern California and the Colorado mountains; and coastal Maine. How was she able to render such distinct milieus so persuasively?

Kathryn Davis: For Jean Stafford, place equals psyche. “I had only to say ‘Miss Pride’s room,’” says Sonia Marburg at the outset of A Boston Adventure, “and at once my feet stood on the tawny rug with its huge faded peonies, and before me was the window seat covered with flat, flowered cushions, at one end of which was a folded afghan, at the other, three big soft pillows on which cherubs floated amongst blue daisies, holding up in their dimpled hands a misty picture of a castle.”

The Mountain Lion begins with Molly and Ralph Fawcett heading home, released from school early due to shared, chronic nosebleeds. “It was a narrow, winding country road they walked along. On either side ran clear small ditches, making a mouth-like sound.” The Catherine Wheel starts on the first day of summer: “Between the marriage elms at the foot of the broad lawn, there hung a scarlet canvas hammock where Andrew Shipley squandered the changeless afternoons of early June.” For Jean Stafford, without place there are no characters, there is no narrative. For Jean Stafford, without place, there is no novel.

LOA: In your afterword to a paperback printing of The Mountain Lion, you have suggested that readers and critics misconstrue the novel as the work of a realist. Do you think the same is true of Boston Adventure and The Catherine Wheel?

Davis: The occult—more specifically the unheimlich, the hidden thing that should have remained hidden but somehow gets released—is crucial to all three of Stafford’s novels, though perhaps most fundamentally to The Mountain Lion. Its presence governs the entire book, and accounts for my sense of the work as uncanny; despite Stafford’s meticulous attention to external, physical detail, an essential truth lies buried, erupting at last in that devastating final scene with Molly on the back seat of the car “propped up like a person” as her brother watches “the road being devoured by the car like an endless red noodle.” Stafford’s descriptive language, which we’ve come to count on for its rendering of the real world, turns strange, but because of the way she has seemed to be proceeding literally all along, the metaphors feel less figurative and more like objective depictions of reality. A Boston Adventure ends with a similarly uncanny—monstrous even, praying mantis-like—image of Miss Pride: “She looked again as she had done when I was five years old in Chichester; her flat, omniscient eyes seized mine, grappled with my brain, extracted what was there. . .”

LOA: Readers trying to account for why these novels aren’t better known have speculated that Stafford’s utter lack of sentimentality about children and childhood has kept her from entering the mainstream. Would you agree?

Davis: It’s certainly true that Jean Stafford never sentimentalized children or childhood. She never sentimentalized anything, as far as I can tell, more or less in the spirit of Henry James, one of her obvious literary progenitors, with whom she also shared a love of complex sentences conveying complex patterns of thought, in direct opposition to our current preference for swift-moving syntax. James, though, wasn’t primarily interested in the subject of childhood—except insofar as a child might serve as a kind of objective correlative for unexpressed adult needs and desires—whereas all three of Stafford’s novels take children, in various stages of development, as their primary focus. Maternal expectations abound when a woman writes about children, and those expectations were abounding more aggressively back when Stafford was writing and publishing. She herself had no children and, to make things worse, the one time she fastened her eagle eye, exclusively, on a mother (A Mother in History, 1966), it was on the mother of Lee Harvey Oswald.

LOA: As the author of eight novels yourself, are there particular things Stafford accomplishes in these works that you especially envy or admire?

Davis: Jean Stafford was an early influence on my work. I read The Mountain Lion around the time I was writing Labrador; at that time her elision of place and psyche proved reassuring to me, essential to my project. I also remain reassured by a quality of tone in her voice, a product of the disconcerting eruption of surreal imagery (that red noodle road, those mantis eyes) within what purports to be the real world, that contributes, finally, to a sense of there being something humorous—albeit sharp as a blade—about even the most serious of circumstances. Following Grandpa Kenyon’s death, Ralph stands in the room with the dead body, listening. “The ladies were in the dining room talking. He could not hear what they said, but he could imagine the shape of their mouths and the kind of thing they would be repeating over and over again in that strange belief all grown-ups seemed to have that no one heard the first time.”

LOA: Stafford is still best known as a short story writer, although we hope this present volume will help start to change that impression. How are the stories different from her novels?

Davis: Generalizing about the stories is difficult. The stories are, needless to say, shorter—hence the material in them is more condensed. I found myself feeling, rereading them, a strong sense of being deeply lodged inside Stafford’s head—and not just in “The Interior Castle,” where it’s her project to make this happen. Another way of saying this would be that the sense of place in the stories is less about geography and more about pure psyche, even though she took pains to arrange the table of contents geographically.

A Library of America volume of Jean Stafford’s short stories, edited by Kathryn Davis, will be published in early 2021.