Old, archived materials of past writers offer new insights into well-known authors and their writing. The collections of Black writers in particular have proven powerful tools for recovering important lost histories and works of art.

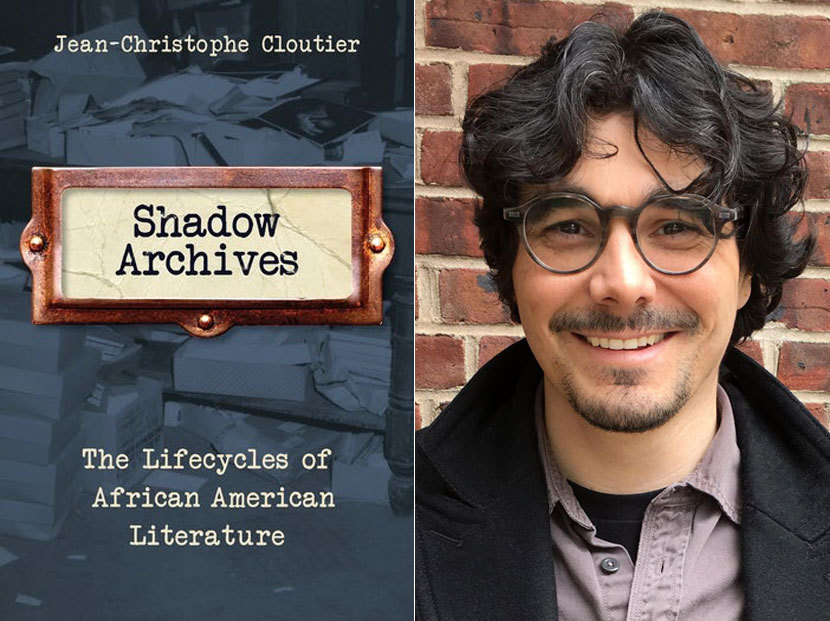

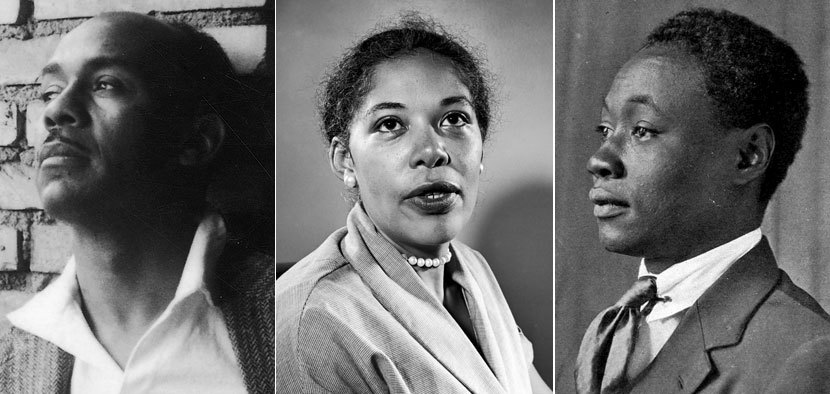

In Shadow Archives: The Lifecycles of African American Literature (Columbia University Press, 2019), Jean-Christophe Cloutier takes the reader on a fascinating expedition into the archives of leading twentieth-century Black writers like Richard Wright, Ann Petry, Claude McKay, and Ralph Ellison, uncovering lost and sometimes altogether forgotten materials that change how we think about the authors and their writing. Along the way, Cloutier poignantly illustrates the often fraught personal and professional relationships among these authors, their work, and those who sought to archive their creative genius. In doing so, he also provides an enlightening account of the unique challenges that many twentieth-century Black writers faced when trying to establish a collection.

Jean-Christophe Cloutier is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, where he teaches modern and contemporary literature, comics, cinema, and archival research methods; previously, he worked as an archivist in Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. In 2016 he edited La vie est d’hommage, a French-language volume of Jack Kerouac’s comprehensive original French manuscripts, and he was the translator of Kerouac’s French writings that appeared in the Library of America volume The Unknown Kerouac that same year. Via email, he answered our questions about Shadow Archives.

Library of America: What exactly are literary archives, what types of materials might they contain, and why is it important for the modern reader to think about them?

Jean-Christophe Cloutier: Literary archives are special collections that were usually built over the course of an author’s life and career, the accumulation of all their stuff, and they can in many ways be a reflection of a lived literary life in its own moment in time.

Literary archives can be a scholar’s Maltese Falcon: the “stuff that dreams are made of,” giving us a window into the compositional stages of a beloved novel, story, or poem. They usually contain myriad manuscript drafts in various stages of completion; personal and professional correspondence; research materials gathered by the author; drafts for aborted, undisclosed, or unpublished pieces; diaries; travel logs; notebooks; photographs; clippings; scrapbooks; daily schedules; phonographs; tape recordings; and various print matter and ephemera. Additionally, they may include first editions and foreign editions; and, if the author was a lifelong packrat, school records, childhood drawings, and mysterious little artifacts that only make sense to the child who once forged them. Sometimes there are objects, things that go with the writing business, like a typewriter or pens; or keepsakes like a special letter opener, a snow globe, a lock of hair, whatever. Or, wonderfully, even things that were lost or accidently misplaced within the filing cabinets or drawers—dentures, forgotten lunch bags, receipts—I’m sure most archivists would have many stories to tell about the kinds of unexpected finds made while processing literary papers. I did find some super-old, used-up Q-Tips once, they were surrounded by dried-up beige elastic bands that now looked like dead worms.

LOA: Shadow Archives focuses specifically on the archival collections of African American writers. Is there something unique about the relationship between archive, literature, and the African American writer that we don’t find with the records, writing, and lives of white writers? Has this changed at all over time?

Cloutier: In a way the whole argument of the book presents an affirmative answer to these important questions. Shadow Archives traces the historical development of Black special collections in the context of the sudden rise of contemporary literary papers in the United States in the mid-twentieth century. The postwar institutional love for literary papers was far from universally distributed. Unlike today, outside of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), only a few repositories—notably Yale University and the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture)—were actively interested in acquiring the papers of Black writers. More often than not, such acquisitions also had to be in the form of gifts and donations on deposit rather than purchases. In contrast, living white authors, British and American alike, enjoyed an intensifying and increasingly aggressive attention from the rare-book and manuscript market—as exemplified by the acquisition record of the University of Texas library (now the Harry Ransom Center)—marking a paradigm shift in value that turned the living writer’s waste basket into a potential goldmine.

Thankfully, the reality today is very different than it was for the writers I discuss in the book. We are in the midst of a big paradigm shift when it comes to Black special collections. For the first time, Black authors are able to fetch sums—in some cases millions—that had previously only been possible for white writers.

| *Read Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem in:* |

|

| Harlem Renaissance: Five Novels of the 1920s |

LOA: Several years ago, you unexpectedly found a lost novel by Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay, which you have since helped make available to the public. Can you describe how you felt when you first realized your discovery? How has the book changed our understanding of McKay since its recovery?

Cloutier: The discovery of McKay’s Amiable with Big Teeth was the primum movens, the first mover, so to speak, that eventually led to my writing Shadow Archives. In fact, I decided to conclude the book by recounting for the very first time the story of that manuscript’s discovery, and to do so as a way of thinking about larger questions of method, serendipity, and the disciplinary blinders that sometimes prevent us from looking in the right places.

I came upon the manuscript when I was interning as a processing archivist in Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library—I was in the early stages of processing the papers of Samuel Roth, a maverick independent publisher who in his heyday had published unauthorized excerpts from James Joyce’s Ulysses. Roth is a fascinating figure in his own right, which is what had drawn me to choose his collection for processing that summer. But the presence of a Claude McKay novel, let alone one that no one had ever heard about, in Roth’s papers was perplexing, and ultimately required years of authenticating work to prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that it was indeed a lost novel penned by Claude McKay.

These days it’s a pleasure to see how much outstanding scholarship is being produced since the novel’s recovery, as scholars around the world are teaching us new ways of seeing and appreciating McKay’s final novelistic achievement. And with the upcoming release of McKay’s other previously unpublished novel, Romance in Marseille, we will soon get the chance to read another delightful narrative tucked away in McKay’s archival sleeve.

LOA: In Shadow Archives, you discuss the concept of the “lifecycle” of literary materials—from published novels to archived ephemera. Can you explain what you mean by “lifecycle,” and can you provide an example of a famous piece of African American literature with an intriguing lifecycle?

Cloutier: “Lifecycle” is a term I learned and borrowed from archival science. It’s a means of understanding the various stages and uses that records and documents go through during their “lifespan” or time in circulation. One of my chief goals in Shadow Archives was to bring into relief the unique powers and functions of writers’ archives through meticulous excavation of previous lifecycles of key literary artifacts preserved in the papers of pioneering African American novelists.

A favorite example in the book is detailed in Chapter Three, a chapter that looks at the photographic work of Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and Gordon Parks. In the winter months of 1947–1948, Ellison and Parks collaborated on a photo-essay project that was supposed to appear in ’48: The Magazine of the Year but the magazine went bankrupt just weeks before it was set to go to the presses. Everything was ready, not only the essay itself, a text called “Harlem Is Nowhere,” but they had also finalized their selections from among the many photographs that Gordon Parks had taken to accompany the piece. Not only that, but Ellison had also composed a caption for each carefully-selected photograph. After the magazine went bankrupt, however, all that work sat unused in Ellison’s files for years—and Parks went on to include some of his photographs in the portfolio that won him a job as Life magazine’s first Black staff photographer. In 1964, when Ellison released his first book of essays, Shadow and Act, he included “Harlem Is Nowhere,” but without photographs.

What I discovered poring over the manuscript drafts of the essay and his research materials preserved at the Library of Congress is that Ellison had returned to the captions he had composed and transformed many of them into sentences that are now part of his masterpiece, the National Book Award-winning novel Invisible Man (1952). With this new evidence unearthed, some novelistic scenes now seem to emerge directly out of this past collaboration, and out of these photographs. For example, in the published novel, once the narrator has escaped the factory hospital and takes his first steps back above ground, his growing inner doubts lead him to pose the same two questions that Ellison had initially composed for one of the captions: “Who was I, how had I come to be?” he asks in the 1952 novel, while the 1948 caption reads, “Who am I? Where am I? How did I come to be?,” and was accompanied by one of Parks’ most famous and best pictures, which I reproduced in the book.

LOA: In Chapter Four, you give an engaging account of your own archival detective work in search of a missing Ann Petry collection, which you do in fact find. What makes Ann Petry such a unique and challenging case study of African American records? Based on your breakthrough finding, what are your hopes for the future of Ann Petry’s work?

Cloutier: Thank you for saying so; I’m glad you found it engaging—Chapter Four is different in style than most of the other chapters because there I was trying to convey both the thrill of literary detective work and a sense of the kind of research required before one can even begin to analyze manuscript drafts. In other words, before any kind of analysis, first you have to find the stuff!

Ann Petry presented a unique challenge in part because she was a fiercely private author who shunned literary fame and destroyed much of her own archive during her lifetime.

In life, of course, Ann Petry exerted a measure of control over what she wanted to leave behind. She concentrated on safeguarding drafts of her fiction; when it came to more personal materials, she thought it was better to destroy that stuff. Petry was also given to redacting passages, excising pages, altering facts, distorting chronologies, and so on. We can be thankful, therefore, that Petry decided to donate at least some of her archive to Boston University. But the Petry Collection at Boston University consists of nineteen boxes and is thus relatively small compared to the collections of a great number of Petry’s contemporaries housed in other major repositories. The Ralph Ellison Papers at the Library of Congress, for example, consists of well over 300 boxes.

What I didn’t expect to find during my visit to BU’s Petry Collection were letters by Carl Van Vechten haranguing Petry to donate her manuscripts to Yale for what was then called the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters. As I chronicle in the book, subsequent research proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that Petry had sent the manuscripts to Yale—a letter from Yale’s librarian acknowledging receipt of the manuscripts, a photograph that appeared in Publisher’s Weekly, commemorating the moment Van Vechten was handed the original manuscript for The Street.

I’m happy to report that since my book’s publication, Yale has at last processed the collection and these manuscripts are now available to researchers. Since Petry’s The Street is the first novel by a Black woman to sell more than a million copies, having the original notebooks and typescripts, let alone the author’s own synopsis and the manuscripts for her second novel, represents an invaluable resource for American literary history. I’m hoping these manuscripts will give us insights into Petry’s novelistic craft, her methods of composition, her motivations behind certain revisions and additions—a task that has incidentally also been made much easier by the recent publication of your Ann Petry volume wonderfully edited by Farah Griffin.

LOA: Your archival research of Ralph Ellison’s photographs, speeches, letters, and unpublished essays has shed new light on him as a writer especially invested in pop culture—comics and superheroes in particular. We were intrigued, for instance, by your analysis of Ellison’s reference in Invisible Man to cartoonist James Thurber’s work. What were your most unexpected and rewarding cartoon-related discoveries, and how do your findings change our understanding of Ellison?

Cloutier: My chapter on Ellison and comics was such a thrill to write and research. Believe it or not, it was way back in my undergraduate days was that I first attempted to write on the relation between Ellison’s novel and superhero comics. That was all simply based on my biased reading of the novel as a comics fan and on having spotted all these references to comics and cartoons like those of James Thurber in The New Yorker. At a particularly surreal moment in his life, Ellison’s narrator asks himself, “Had life suddenly become a crazy Thurber cartoon?”—which prompted me to look deeper into Thurber’s career as a cartoonist and writer. I’ve always had a soft spot for his story “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” The Thurber reference in the novel suggests that Invisible Man reads “highbrow” rags like The New Yorker, but he also makes references to other cartoons that are more “lowbrow” or populist like Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, a comic strip that was popular in the 1930s and 1940s. Invisible Man also directly refers to other cartoon, radio, and film superheroes like The Lone Ranger and Popeye. And the novel also includes more general references to “comics”—for instance the three zoot-suiters in the subway are reading a comic that they pass around to each other in the train car.

Comics were something Ellison had spent a great deal of time thinking about, especially their relation to American myths and fantasies, as new urban models of leadership, and as reading material that kids across the country were just devouring on a daily basis, especially in the days before television. In one piece he even makes direct reference to Batman—“Harlem’s little Batmen,” he says, during a speech on American outlaw fantasies.

I think for me the most rewarding find was a series of photographs taken by Gordon Parks during his 1948 collaboration with Ellison on “Harlem Is Nowhere” where we see young Harlem boys sitting outside on these wooden crates and blocks of ice—it’s winter time—and they are reading comics. I reproduce two of these images in Shadow Archives_—one is of three boys huddled together with a single comic and they appear to be in deep, serious conversation about it. The photograph seems to be a direct inspiration for the scene I mentioned earlier in _Invisible Man where the three zoot-suiters are passing a comic around in the subway car.

The chapter demonstrates how all this changes our understanding of Ellison—who historically had never been accused of reading comics—so I’d invite your readers to pick up the book if they want to learn more.

LOA: Are there any current exhibitions or publicly accessible displays of literary materials that you’d recommend to any of our readers who might be interested in seeing literary artifacts up close?

Cloutier: If you’re lucky enough to live in the New York area then you usually can’t go wrong with the 42nd Street New York Public Library, the Morgan Library & Museum, or the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. And those are just three of the main repositories that regularly display unique, wonderful, rare literary artifacts—there are plenty more depending on where your personal interests lie. The Morgan just opened its exhibit on French absurdist Alfred Jarry, inventor of ‘Pataphysics—the science of imaginary solutions. Jarry remains one of my all-time favorite authors and human beings.

If you’re interested in post–’45 radicalism and avant-garde, Johan Kugelberg’s Boo-Hooray regularly shows truly unique materials. If you’re passing through Philadelphia there will soon be some exhibitions and events celebrating Herman Melville’s bicentennial, as we did for Walt Whitman at 200. At the University of Pennsylvania, where I teach, we also recently had an outstanding exhibition showcasing some of the highlights in our Gotham Book Mart collection called Wise Men Fished Here—Penn acquired the famed bookstore’s collection and it took David McKnight, our Rare Book & Manuscript Director, and his team over a decade to process. So many treasures in there, including a trove of Edward Gorey materials.