War necessarily involves abstraction. Men (and more recently women) become soldiers; soldiers become troops, armies to be deployed, positioned on maps. Human lives become casualties; if civilian, collateral damage. What would otherwise be murder becomes, somehow, something else.

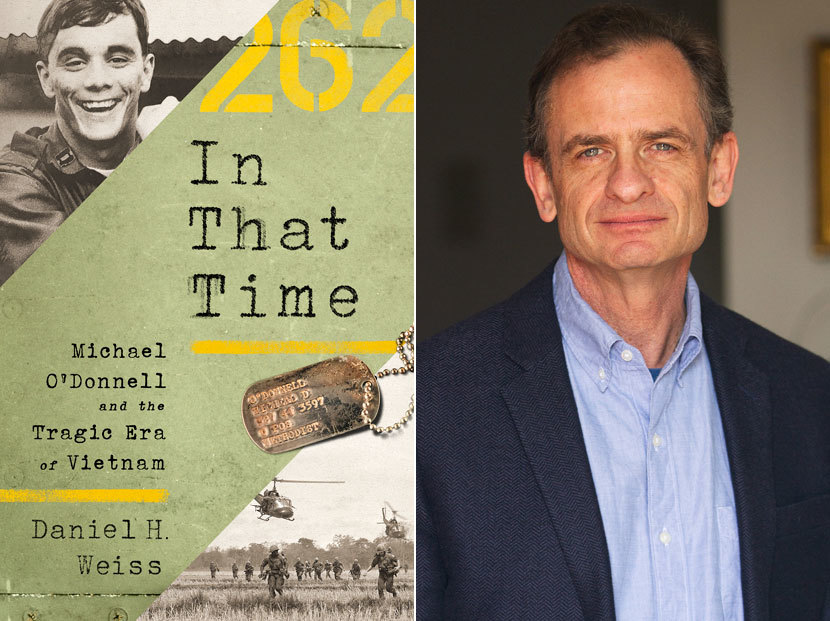

It is the power of an individual story, as Daniel H. Weiss reminds us with his remarkable new book, to cut through such abstractions, and expose the reality of war. In That Time: Michael O’Donnell and the Tragic Era of Vietnam tells the story of the American experience in Southeast Asia through the life of Michael O’Donnell, a bright young musician and poet who volunteered and became a helicopter pilot in Vietnam.

As a pilot, O’Donnell served in one of the most dangerous roles of the war, enduring long days of boredom punctuated by extreme episodes of stress and horror. Throughout, O’Donnell turned to poetry to give voice to his feelings and reflect on the tragedy unfolding around him. In 1970, during an attempt to rescue fellow soldiers stranded under heavy fire, O’Donnell’s helicopter was shot down over the jungles of Cambodia. He remained missing in action for almost three decades.

The book’s title is drawn from O’Donnell’s poem “Letters from Pleiku,” written on New Year’s Day in 1970 and discovered in his papers after his death. A poignant plea for remembrance, the poem would circulate widely and informally among soldiers and veterans in the months and years that followed and is now considered one of the most powerful literary works to have emerged from the war.

It was the encounter with this poem that led Weiss, an art historian by training, and the current president and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, on the journey to write this book.

Library of America: Can you describe how this book came to be? What was it about O’Donnell’s poem that you found so compelling?

Daniel H. Weiss: It was indeed Michael’s poetry. I first encountered his most well-known poem, “Letters from Pleiku,” in Harold Evan’s magisterial The American Century and I was deeply moved by O’Donnell’s modest request that we simply remember those who were being sacrificed for an ill-fated cause that meant so little. As I learned more about this remarkable young man, I was drawn to the idea of telling his story within the context of all that happened to America in the 1960s.

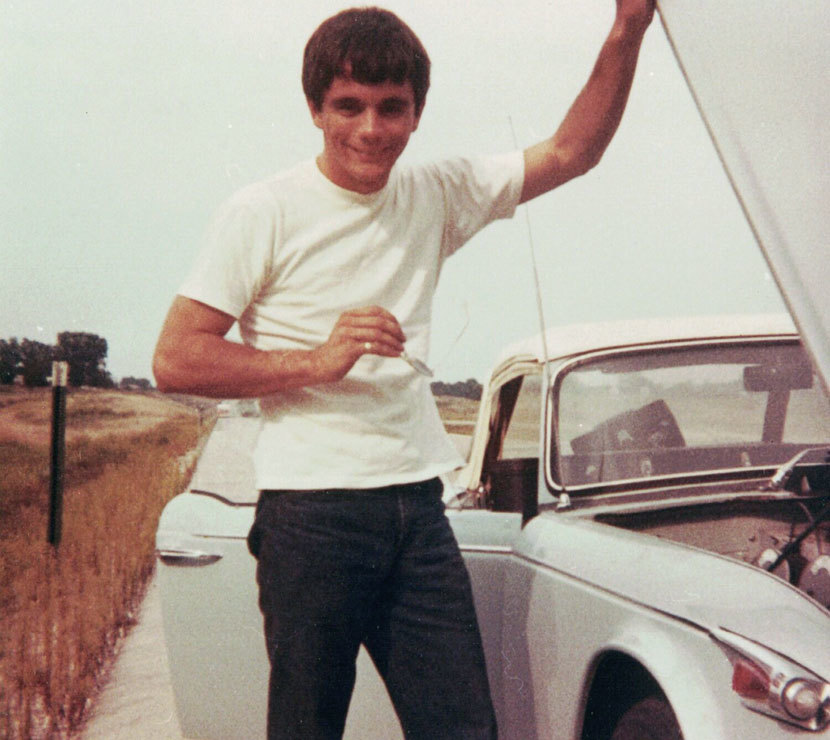

LOA:O’Donnell was clearly very talented, and you’ve very helpfully created a website where we can read his poems and listen to his songs. And yet he also emerges as a pretty ordinary young man, neither a particularly gifted student, nor especially politically active. Was this part of the appeal he held for you as a subject?

Weiss: Yes, it was. In many ways Michael O’Donnell was, like so many fellow soldiers, an ordinary American kid who became engulfed by the war, ultimately becoming one of 58,220 who never returned. In telling his story, I wanted to describe the ways in which his experience was like that of so many others while also highlighting the ways in which he was exceptional—as a poet, a songwriter, and a vibrant young man with so much talent and promise. This is part of what makes all wars such tragic events: each person lost to war loved life as we do, and each had a story. There is nothing inevitable about who is lost in war, and statistics tell us nothing about who these people were and what they lived for.

LOA: Your retelling of O’Donnell’s final mission is especially harrowing. How were you able to recreate it so vividly?

Weiss: There is a great deal of surviving evidence from this particular mission, which allowed me to get very close to the events of the day. Several of the witnesses to the battle—all helicopter and fixed wing pilots—provided written reports immediately afterwards and I was able to interview Jim Lake, the mission commander and a good friend of O’Donnell’s. With various eyewitness accounts and much recorded detail, I wanted the reader to experience the events as they unfolded and to get some sense of what trauma looks like in real time.

LOA: Braided together with your account of O’Donnell’s life is a history of the political context of the Vietnam era, in which you ask deeper questions about how a democracy goes to war. As you show, and as the recent publication of “The Afghanistan Papers” in The Washington Post reminds us, secrecy and willful misrepresentation on the part of political and military leaders presents a perennial challenge for citizens attempting to assess the causes and conduct of wars fought in their name. Have the lessons of Vietnam been learned? Can they be, given the elaborate national security structure we have built?

Weiss: It seems increasingly clear as the Vietnam debacle fades into the distance that we have not learned the lessons we should. In its own modest way, Michael O’Donnell’s poem has helped us to remember that those who do the fighting should not be confused with those who are responsible for the policies that send young people to war. We have learned that lesson and we now do more to recognize the sacrifice soldiers make on our behalf.

However, for me the greatest lesson we have not learned concerns what we should expect from our leaders. In a rapidly changing world filled with uncertainty, the most important quality leaders should have is what Emerson calls “character,” a capacity to wield power with humility, to learn from others, to operate from principle, and to be accountable. In navigating complex political and military issues—in Vietnam and thereafter—our leaders have for the most part not led with these qualities at the forefront. If my readers take nothing else from this book, I hope they have a greater appreciation for the importance of leaders, who, as Emerson wrote, “serve ultimately as the conscience of the society to which they belong.”

LOA: You bookend In That Time with vignettes of Arlington National Cemetery, perhaps the nation’s most profound exercise in collective memory, where Michael O’Donnell rests. Why was it important to frame your story in this way?

Weiss: In many ways Arlington has become the nation’s center for recognition and remembrance of those who fought our wars. I was interested in how this remarkable place became what it is today, how it has changed, and why it matters that we have such places. As we seek to understand the place or war and sacrifice in the life of our democracy, Arlington stands for something deeply and enduringly important. And of course, this is where the lives and sacrifices of Michael O’Donnell and so many others can be remembered.

Daniel H. Weiss is the president and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Formerly president of Haverford College and Lafayette College and James B. Knapp Dean and professor of art history at the Krieger School of Johns Hopkins University, he holds a PhD from Johns Hopkins and an MBA from the Yale School of Management. He has been a Library of America Trustee since 2015. In That Time is his sixth book.