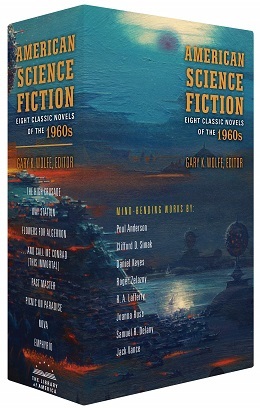

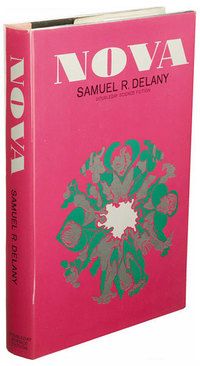

Library of America has just republished Samuel R. Delany’s 1968 novel Nova in the two-volume anthology American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, edited by Gary K. Wolfe. In the following guest column, cultural critic and Nation national affairs correspondent Jeet Heer explores the context from which Nova emerged and suggests some of the reasons for its classic status more than fifty years later.

By Jeet Heer

Like math, like music, like gymnastics, science fiction is an endeavor that attracts the energy of the young. In the summer of 1967, shortly after he had finished writing Nova, Samuel R. Delany took an inventory of the youthful prodigies of the genre. “Isaac Asimov’s first story appeared when he was eighteen,” Delany noted. “John Brunner’s first novel when he was seventeen; Theodore Sturgeon’s first story when he was twenty. The list of SF [science fiction] writers who were in print before they could vote is impressive.”

The same is true of Delany himself. The voting age in 1962 was twenty-one. That year saw the release of Delany’s first published novel, The Jewels of Aptor, written when he was nineteen and released when he was twenty. It was followed at a clip of one or two books a year, resulting in eight more novels by 1968, culminating in the best book of his youth, Nova (1968). His early novels came out in such quick succession that many in the science fiction community assumed “Samuel Delany” was a house brand used by his publisher, Ace Books, to cover a multitude of authors. This idea was bolstered by Delany’s lack of any social connections to the world of science fiction fandom.

It was only after his appearance at the 24th World Science Fiction Convention, held in Cleveland in 1966, that Delany’s existence was recognized, which led to the quick consensus that he was a leading figure in the field. In 1967, the contentious editor Harlan Ellison wrote that Delany gave “an indefinable but commanding impression that this was a young man with great work in him.” The following year, Algis Budrys, a respected novelist and at the time the sharpest critic in science fiction, hailed Nova by saying the novel proved that “right now, as of this book” Delany is “the best science-fiction writer in the world, at a time when competition for that status is intense.” Delany was all of twenty-six years old when he earned that accolade.

If Delany was celebrated by some as a wunderkind possessing (in Budrys’ words) “star quality” not everyone appreciated the future he was offering. Delany’s biography made him an anomaly in the world of science fiction, at the time an overwhelmingly white genre with a streak of political conservatism. Delany was a gay, African-American man who, at the time, lived off-and-on in an open marriage with the white poet Marilyn Hacker (who would later identify herself as a lesbian). A queer sensibility ran through much of his fiction, notably the Hugo–winning short story “Aye, and Gomorrah. . .” (1967).

Equally evident in Delany’s fiction was a desire to depict a culturally and racially heterogeneous future, a goal that distinguished his fiction in a genre where the norms of the white American middle class was often presented as a kind of default mode even when representing putatively alien cultures. To be sure, some writers made a diligent effort to present a multiracial future, notably Robert Heinlein, whose Starship Troopers (1959) impressed the teenage Delany for the casual way it handled the fact the main character was a person of color and of Filipino descent. But Heinlein’s characters, whether white or people of color, all talk the same: there is no felt sense of class or cultural diversity in his work. Delany, by contrast, never depicts a monoculture: his characters are always situated by language, history, and class.

Lorq Von Ray, the crazed space captain who serves as the anti-hero of Nova, is of Norwegian and Senegalese descent. The crew that von Ray commands is also racially mixed, with characters who, in inadequate shorthand form, can be described as African, Asian, or Romani (the Mouse, referred in the book by the then commonly used term as a Gypsy).

Before Nova was published, Delany’s agent Henry Morrison offered it for possible serialized excerpt to John W. Campbell, the editor of the best-selling American science fiction journal Analog. Although Campbell was a cranky and polarizing figure in the field, his editorship was influential and he played a key role in midwifing many classic works, notably Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, Robert Heinlein’s Future History stories, and Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Campbell told Morrison he liked Nova but didn’t think his readers would accept a black protagonist.

It’s easy to write off Campbell as an embarrassing reactionary. Analog by 1968 was well past its prime and had devolved into a magazine publishing stories of heroic engineers always besting their foes, ranging from space aliens to government bureaucrats. The fiction wasn’t enhanced by Campbell’s habit of writing contrarian editorials celebrating smoking, slavery, and the segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace.

But Delany also fared nearly as badly with an editor who was Campbell’s polar opposite, Michael Moorcock, the impresario behind England’s New Worlds magazine. In the pages of his journal, Moorcock was a leading proponent of “New Wave” science fiction, a movement to modernize the genre by bringing in the techniques of experimental fiction and a focus on pressing social and political debates.

Delany published a story in New Worlds and the capacious label of New Wave science fiction was often fixed on him. Certainly, he shared one aspect of the New Wave agenda. He had grown up reading both science fiction and modernist writers like James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, and Arthur Rimbaud. Like such indisputable New Wave masters as J. G. Ballard and Brian Aldiss, Delany eschewed slapdash pulp writing and aimed to write science fiction with the same linguistic inventiveness of the high modernists.

Yet despite this important commonality, Delany was never at ease with the New Wave movement. “Basically, during the sixties, Moorcock and the writers associated with the New Wave did not particularly enjoy my work,” Delany told anthologists Kathryn Cramer and David Hartwell in 2006. “Though we all got along well socially, Moorcock told me that the only book of mine he liked enough to publish himself was Empire Star—no doubt because the political allegory of North American slavery and the LII was so clear. But when Nova was reviewed in New Worlds by M. John Harrison, the basic thrust was: What a shame someone so talented is wasting his time with this far future space opera nonsense.”

The preferred mode of New Wave science fiction was near-future extrapolation. In Nova and Babel–17 (1966), Delany unabashedly embraced space opera, at the time a déclassé sub-genre within science fiction. Nova is set in the far future (the thirty-second century) in a universe of marvels like faster-than-light space travel, countless colonized planets, and widespread merging of humans and machines into cyborgs. (The way Delany’s characters jack into technology planted the seeds for a subgenre that would flourish in the 1980s: cyberpunk).

The narrative involves nothing less than a battle between feuding aristocratic clans for the fate of the universe. This was operatic in more ways than one: Lorq Von Ray is not a character with an internal life but a larger-than-life myth figure, part Ahab and part Prometheus.

This type of exuberant space opera was very much not in fashion in science fiction in the 1960s. Science fiction was a ghetto literature, but there was a hierarchy even in that ghetto. Readers of Campbell’s Analog prized “hard science fiction” that celebrated rationality and allegedly played by the rules of known physics. Moorcock’s New Worlds upheld the value of science fiction that savagely satirized the contemporary media-saturated world. Both Analog and New Worlds looked down on slam-bang planet-hopping space opera.

Delany has a recurring habit of picking up genres that are snobbishly dismissed by other writers and trying to write them with literary care. He’s done that not just with space opera but also sword and sorcery (in the Nevèrÿon novels), superhero comics (his abortive 1972 run on Wonder Woman) and pornography (in novels like Hogg and Mad Man). It seems to be one of Delany’s credos that no genre is beneath contempt, that a good writer can work with any material.

Delany’s recuperation of space opera was as influential as his role as a precursor to cyberpunk. Nova and another Delany novel, Babel-17 (1966), were important forerunners to the “space opera renaissance” that picked up speed in the late 1970s and continues to define the field to the present. Without Delany, it’s hard to imagine the work of Lois McMaster Bujold, Iain M. Banks, Dan Simmons, and countless others.

Nova is in part a meditation on novel writing. It’s set in a socially static world where the novel as an art form has become obsolete. Part of the promised rebirth depicted in the book is of the social conditions that make novel writing possible.

As writer D. J. Johnson points out, the word “nova” has the same etymological roots as the word “novel” (both grounded in the Latin word for new, novum). The two sides of Delany’s own artistic personality are shown in the contrasting characters of Katin Crawford, a cerebral would-be novelist, and Pontichos Provechi (a.k.a. the Mouse), a street urchin who makes money playing the “sensory syrynx” (a device that lets him conjure up sounds, smells, and 3-D images).

Like Crawford, Delany is a very deliberate writer who filled up countless pages of his journal planning out his ideas. But Delany in the early 1960s was also a street musician like the Mouse. Delany’s folk singing in the coffee houses of New York and Europe often earned him more money in the early 1960s than novel writing, and was a crucial source of income.

Part of the argument of Nova is that a novelist has to be both an intellectual like Crawford and an instinctive artist like the Mouse: the artist has to be both theoretically ambitious and alive to sensory experience.

In Nova, we see that Delany’s revitalization of space opera took place on a sentence by sentence level. Delany’s synesthetic prose achieves the same effect as the Mouse’s “sensory syrinx.” Here’s a description from the first chapter of the night sky on Triton:

The shrunken sun lay jagged gold on the mountains. Neptune, huge in the sky, dropped mottled light on the plain. The starships hulked in the repair pits half a mile away.

Delany, here and in all his best works, gives us a future we can immerse ourselves in, a future as dense, diverse, and strange as reality itself.

Jeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent at The Nation and the author of In Love with Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014). The latter book contains essays on science fiction writers Robert Heinlein, Philip K. Dick, and Stanislaw Lem.