For thirty-five years, New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof has been one of the world’s leading figures in drawing international attention to humanitarian crises—from Tiananmen Square to Darfur, from Iraq to Myanmar, and many places between. His illuminating articles, columns, and four books have earned him two Pulitzer Prizes, a Dayton Literary Peace Prize, an Anne Frank Award, and the respect and gratitude of the international community. Bill Clinton remarked that “There is no one in journalism . . . who has done anything like the work he has done,” and Joyce Barnathan, the president of the International Center for Journalists, has called him “the conscience of international journalism.”

On October 3, the United Nations Association of New York honored Kristof with its Lifetime Achievement Award, presented in recognition of the decades he has spent tirelessly bringing attention to the realities of human trafficking and modern–day slavery. Because a good chunk of Library of America’s catalog engages with the history of civil rights and slavery in America, we reached out to Kristof for his unique perspective as an influential contemporary journalist.

His answers provide insights into journalism’s role in meeting the social and political challenges of the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. He gave us a sneak peek at his new book, Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope, which goes on sale next month.

Library of America: What first drew you to crisis journalism, and why have you remained so committed to it over the course of your career as a columnist?

Nicholas Kristof: I’m not sure I’d call it “crisis” journalism because crises tend to get attention, while I aim to cast a spotlight on issues that don’t get enough attention. It’s maybe indicative of the neglect of these issues that we don’t have a good name for this kind of journalism. But the reason I do it is that the stories haunt me, and attention does make a difference.

When I made my first trip to Darfur, I never imagined I would make a second trip. But when you see survivors of massacres hiding out from militias trying to kill and rape them, it’s very hard to come back to New York and pontificate about some Washington row. And so I made another trip. And another. And so on.

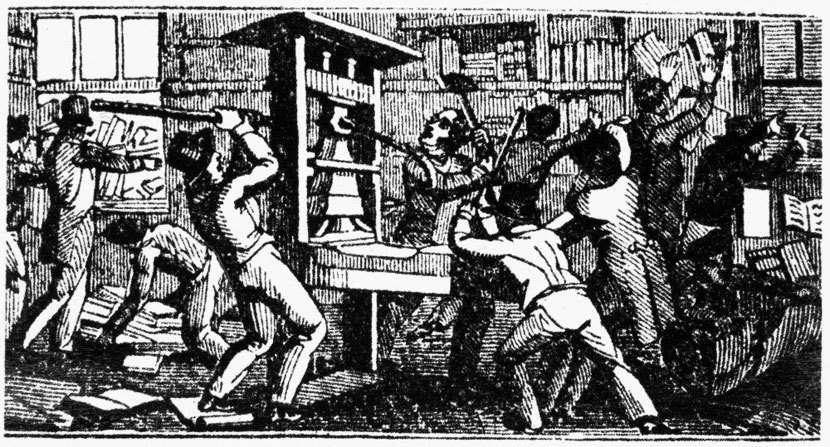

LOA: You’ve focused much of your work on human trafficking and modern slavery, contemporary crises with deep historical roots. In this regard, you follow in the footsteps of American activist-journalists like William Lloyd Garrison, Horace Greeley, and Elijah Parish Lovejoy, who were crucial in raising public awareness in the North about the horrors of slavery in the South. Have you taken inspiration from the long tradition of American antislavery writings? What might citizens of the twenty-first century stand to gain by revisiting the historical writings that laid the groundwork for the abolition of slavery in the nineteenth century?

Kristof: I’ve definitely been inspired by the writings of those American writers who took on slavery, and also by those who decades earlier raised the issue in Britain. It’s striking that throughout the millennia, everyone pretty much accepted slavery as a fact of life. Socrates doesn’t object to it, nor does Jesus, and moral philosophy was largely oblivious—or else saw slavery as sad but inevitable. Ethical behavior meant being nice to slaves, not uprooting slavery. Quakers were just about the only people who objected to the institution itself. Then a few rabble-rousers in Britain, like William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, and Olaudah Equiano, started speaking up in the 1780s, and they changed the world and our moral view. They did it in part by explaining painstakingly the brutality of slavery, and also by cultivating empathy for those who were enslaved. Until that time, mass protest movements had always been by people defending their own rights, but the Abolitionist movement was the first mass movement on behalf of others. And, yes, that is utterly inspiring!

LOA: Journalism was again a powerful tool in twentieth-century American struggles for civil rights and social justice. Are there any reporters from the civil rights era who stand out as especially influential or inspirational to you?

Kristof: There were many great reporters covering the civil rights struggle, and risking their lives to do so. People like Claude Sitton and John Herbers risked their lives to highlight the brutality and inequity of the Jim Crow South and forced Americans to pay attention. Rep. John Lewis has described how when the Freedom Rider buses reached Montgomery, mobs attacked the journalists first, to put them out of commission.

I have particular admiration for those journalists who were themselves sons of the South, and who risked their newspaper businesses and the respect of all those around them to do what they thought was right. In some sense they “betrayed” their family and friends to uphold higher moral values. It would have been so much easier to be quiet or write mushy calls for restraint on all sides; instead, they stepped up and showed physical and moral courage in pursuing heroic journalism.

LOA: With this significant history in mind, what new challenges does journalism currently face that past generations may not have had to deal with, what’s at stake, and how should we meet those challenges?

Kristof: One big challenge is the business model. The newspaper industry has lost more jobs than the coal industry, and there are large swaths of the country that no longer have a local newspaper. The New York Times and Washington Post are developing a business model for national and international coverage, but we still don’t have a good way to pay for local journalism that is the life blood of civil society.

In this challenging business environment, news organizations tend to pursue stories that will generate a reliable audience. Right now, that means President Trump. And obviously Trump is an important story that should be intensively covered, but there are other important stories as well that are being lost. I think we’ve hugely under-covered the drug epidemic, for example, and the decline in American life expectancy. It’s outrageous that American life expectancy has declined three years in a row, for the first time in a century, and that this has not happened in other countries but is a feature of American life—and policy failures.

LOA: You and your wife Sheryl WuDunn are preparing for the release of your fifth book together, Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope, which addresses working-class America’s deepening crises with addiction, economic decline, and failing government policy. It is also your first book to focus exclusively on a domestic crisis. What prompted this shift of focus, and did it have any surprising effects on your research and writing process?

Kristof: I was reporting around the world on humanitarian catastrophes, and then I would periodically return to my hometown in rural Oregon, where my mom still lives on the family farm. And I realized that my beloved hometown was a humanitarian catastrophe. A quarter of the people on my old school bus died, of drugs, alcohol, suicide, and reckless accidents. This was an area that had thrived for most of the twentieth century, and then it just collapsed when jobs went away in the 1980s. I saw this as part of a disintegration of working-class communities across America, causing enormous suffering, undermining our country’s competitiveness, and leading to the election of a president I considered a disaster. When historians look back, I think they’ll see this disintegration as one of the most important things happening in early twenty-first century America, and we wanted to call attention to it—and hopefully leverage that attention to get better policies.

So Sheryl and I wrote about this destruction of working-class America, telling the story partly through the kids on my old school bus. For example, we wrote about the Knapps, who lived nearby. There were five kids, the oldest my classmate, and they were smart and capable—and four of the five are now dead. The youngest sibling survived mostly because he spent thirteen years in prison and away from drugs.

I have to say, this has also been a much more painful book to write than our previous books. It’s one thing to write about suffering in China or in a Sudanese refugee camp; it’s another to write about your seventh-grade crush, Mary, and her struggles with meth and alcohol, or her years homeless. My old friends like Mary were so candid in telling their stories, including deeply embarrassing elements, and they did so because they wanted Americans to realize what is going on—and because they trusted us. It’s a huge responsibility, and I want to make sure that their faith was well placed.

LOA: As we’ve discussed, journalism has long played an important role in American society and politics. How does a book like Tightrope compare to the work of earlier American writers and journalists? What do you hope the book might achieve, especially considering its release in an election year?

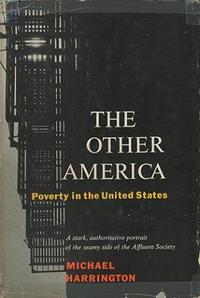

Kristof: We modeled Tightrope in part on the great Michael Harrington book, The Other America, published in the early 1960s. It opened the eyes of America to those left behind and helped inspire the War on Poverty; we would be thrilled if we could in some small way have a similar effect. The 2016 election was fought in part against the backdrop of this large population left behind, but incredibly Donald Trump was the one who won those votes. We hope Democrats will fight for those votes and speak to the betrayal of working-class voters.

One thing we admired about Michael Harrington was that he didn’t sugarcoat poverty or see some great nobility in it; he also acknowledged that self-destructive behaviors are real. We likewise are pretty frank about the capacity of people to make bad choices—but we also show that they are often propelled from childhood on a trajectory that will lead them to make bad choices. We argue strongly that if we’re going to have a conversation about personal responsibility, we also need to have one about our collective responsibility. We need to change the narrative away from personal bad choices to one of national policy to create opportunity.

LOA: One unique aspect of your journalism is that you don’t simply identify problems—you suggest thoughtful solutions to them. Many of our readers may want to know how they can contribute to the causes you champion. Can you suggest one simple way for ordinary people to help create change?

Kristof: Yes, in Tightrope we outline policies that would make a huge difference. We argue that what we lack isn’t the toolbox but the political will—and we hope candidates in 2020 will pillage these ideas for themselves!

Two areas we emphasize are jobs and early childhood. A monthly payment doesn’t compensate a person for a lost job; it doesn’t provide dignity or self-esteem, and it’s not correlated to happiness the way a job is. Likewise, we argue that the greatest bang for the buck comes from helping young children. The evidence is just overwhelming on this front, so we’d like to see more philanthropy targeting young children. Groups like Reach Out and Read and Reading Partners are terrific and need more support.

But I’d also make the point that philanthropy isn’t enough. We would never dream of building an interstate highway system with individual volunteers and donors each building a few square meters of highway. In the same sense, we can’t build a robust network of pre-schools with volunteers and charity. So I hope people will lobby their members of Congress through organizations like Results. We offer advice in Tightrope both for philanthropy and for lobbying.

One of the exciting things for us with our previous books was how often readers and book clubs finished the book and then got started doing something. We hope that will happen again with Tightrope.