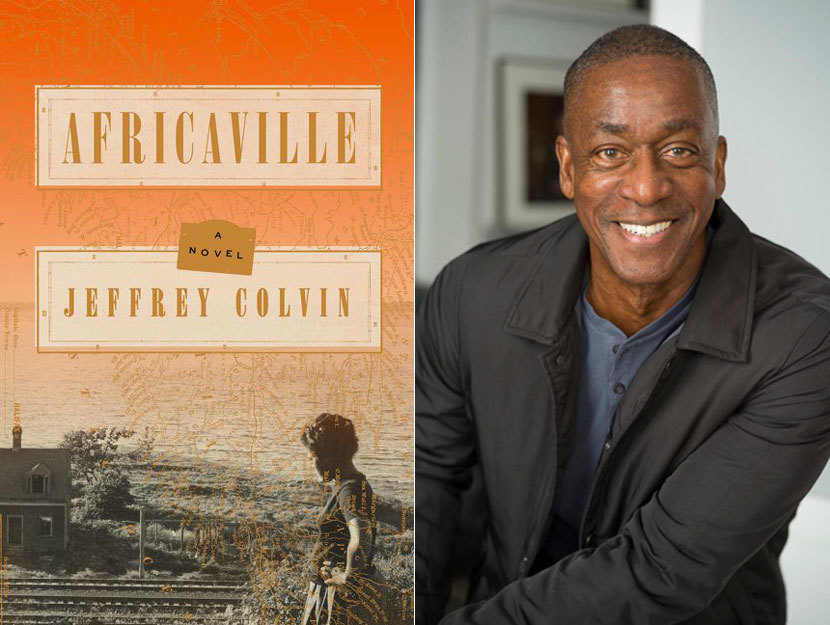

Our series of guest posts by contemporary writers resumes today with a contribution by Jeffrey Colvin, whose debut novel Africaville arrives this week from the HarperCollins imprint Amistad Books.

A first novel of unusual scope and ambition, Africaville is a multigenerational family saga that extends from Nova Scotia to Montreal and then across the U.S. border to New England and the deep South. Advance praise for the book has included favorable comparisons to the work of Edward P. Jones and E. L. Doctorow, and Publishers Weekly calls it “a penetrating, fresh look at the indomitable spirit of black pioneers and their descendants.”

Below, Colvin sheds light on two of the novels that inspired him during the long genesis of Africaville. Perhaps appropriately, given the boundary-crossing, transnational nature of his own book, he focuses on a classic of the Harlem Renaissance and a contemporary epic by an Indian-born Canadian writer.

By Jeffrey Colvin

Over the nearly twenty years I spent writing my debut novel, I have been influenced by many works. Though I read widely, my initial concerns were about how best to depict a dynamic black community. Since I had grown up in a black community, I worried that I would perhaps miss important elements because of being too close to the material. My novel benefited greatly from my reading of works by Zora Neale Hurston, including not only her widely admired, seminal work Their Eyes Were Watching God, but also her brilliant debut novel Jonah’s Gourd Vine and her engaging autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road. In attempting to depict a vibrant community with an engaging cast of characters I read many wonderful story collections, especially Dubliners by James Joyce, Lost in the City by Edward P. Jones, and The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros.

The challenges of crafting a novel with a large scope and writing about characters very different from me led me to two novels that remained close by during the entire writing process: Passing (1929) by Nella Larsen and A Fine Balance (1995) by Rohinton Mistry.

Set in 1920s Harlem, Larsen’s novel is about two friends who try to maintain their relationship amid the complications of one of the friends passing as white. When discussing my process for completing my novel, I never fail to mention how I consulted Larsen’s novel during the time I was struggling to depict how the pull of a community like Africaville—a settlement founded in the nineteenth century by formerly enslaved people from the Caribbean and U.S.—could affect a family over several generations. I knew what might pull the second and third generation of descendants of the Sebolt family toward cherishing the town where their ancestors lived, including its unique history and the continued efforts by former residents to keep the town’s memory alive.

Deciding what forces would pull subsequent generations away from Africaville turned out to be a more complicated endeavor. Kath Ella Sebolt—the matriarch of the family, who grew up in the village that became Africaville—isn’t light enough to pass for white. Her desire to improve her life leads her to distance herself from the village by moving to Montreal. Her son, Etienne, the second generation, is light enough to pass and does so, even hiding his past and his family connections from his son, Warner. Etienne’s struggle is more internal as he confronts the emotional toil this decision inflicts. Warner’s struggle is more external. After he learns as an adult that he had a black grandmother, his attempts to reconnect with the former residents of Africaville require that he overcome their reluctance to accept him as part of their community. Both kinds of struggle are dealt with powerfully in Larsen’s novel.

I was drawn to Mistry’s A Fine Balance because I had read that parts of it are set in an unnamed city by the sea. This information was both relevant to my novel about a coastal village and intriguing. I was soon immersed in the lives of powerful characters who seem to spring alive on the page. Set in the mid-nineteen-seventies and grand in its scope, the novel addresses many of the themes and issues I explore in Africaville. The often–unbridgeable gap between the British and Indians in Mistry’s novel might well be echoed in the estrangement that members of the black communities I write about feel toward the wider white world in which they struggle under poverty and oppression. The novel took me to unfamiliar terrain where Mistry brilliantly depicts the sights, sounds, and smells of public and interior spaces. I was taken with so many of the characters, whether they were under the duress of onerous health problems brought on by poverty or struggling to address family strife.

Jeffrey Colvin is a former Marine and a graduate of the United States Naval Academy, Harvard University, and Columbia University, where he received his MFA in fiction. His writing has been published in Painted Bride Quarterly, Rain Taxi Review of Books, The Millions, and The Brooklyn Rail, among other outlets. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and an assistant editor at Narrative magazine. Born and raised in Alabama, Colvin currently lives in New York City.