In one her later poems, “Five Flights Up,” Elizabeth Bishop marvels at the insouciance with which a bird and a dog outside her window greet the new morning, unburdened by shame or regret:

—Yesterday brought to today so lightly!

(A yesterday I find almost impossible to lift.)

Bishop’s life was marked by significant tragedy, including the early loss of her parents, child abuse and chronic ill health, and the deaths of lovers and dear friends. Yet she was able not only to carry this weight but also to transmute her pain and dislocation into a brilliant body of work that would make her one of America’s most admired poets. As her friend James Merrill once observed, “Elizabeth had more talent for life—and for poetry—than anyone else I’ve known.”

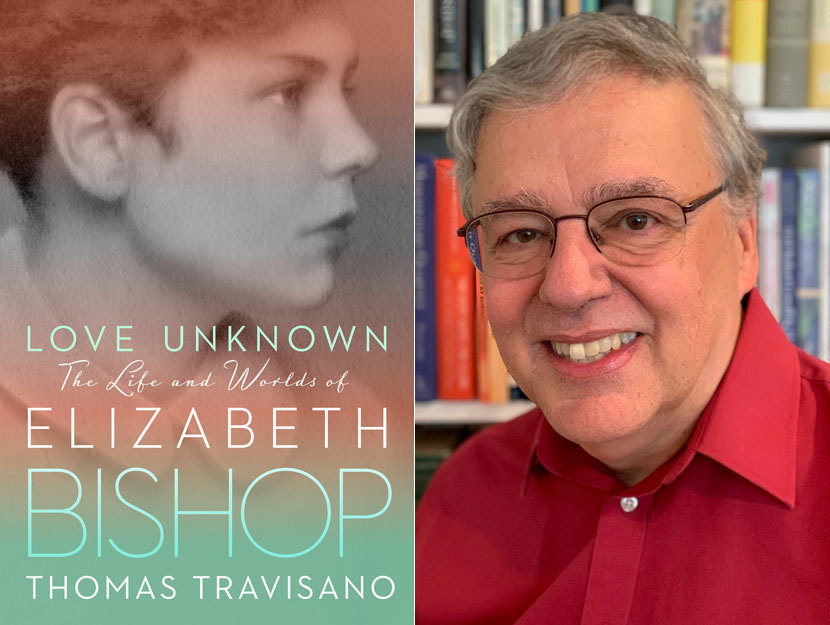

In Love Unknown: The Life and Worlds of Elizabeth Bishop, noted Bishop scholar Thomas Travisano weaves together the many strands of Bishop’s well-traveled life into what Publishers Weekly, in a starred review, calls “a definitive biography.” Travisano, who is professor emeritus of English at Hartwick College and the founding president of the Elizabeth Bishop Society, has been studying the poet for more than forty years. In this new book he draws on extensive research and new interviews and on Bishop’s correspondence with fellow poets Robert Lowell, Anne Stevenson, and May Swenson, as well as newly discovered letters to her psychiatrist—all of which provide surprising details about her life and fresh readings of her poems. We caught up with him to ask a few questions about Bishop’s extraordinary life, and why her reputation seems to continue to grow as time passes.

Library of America: What first drew you to Elizabeth Bishop’s work? Did you ever have occasion to meet or correspond with her?

Thomas Travisano: I began a doctoral thesis on Elizabeth Bishop in 1977, just after the publication of her masterful final book, Geography III. In 1978, I had the opportunity to speak with Bishop for more than an hour over breakfast following a reading she gave at the University of Virginia. During this hour she regaled me with a long stream of hilarious stories. At the same time I felt she was a little bit wary of this young scholar who likely knew things about her life and world that she was not sure that she wanted disclosed. After her death in 1979, I had the opportunity to speak repeatedly with many friends from Bishop’s final years at Harvard and elsewhere, including Lloyd Schwartz, Frank Bidart, Jane Shore, Kathleen Spivack, Emanuel Brasil, Mark Strand, Roxane Cumming, Joseph and U. T. Summers, Mildred Nash, David Staines, Alice Methfessel, and many others. I had exchanged several letters with Bishop herself, mostly about professional matters, but it was this personal contact with her and with her friends that mattered most to my biography.

LOA: You had access to material unavailable to Bishop’s earlier biographers. What was your biggest discovery?

Travisano: I was the first to see Bishop’s extraordinary 1947 letters to her psychiatrist Dr. Ruth Foster, which only became available to scholars in February 2013. These letters, which explore her traumatic experiences in early childhood, her partial emotional recovery in her teens, her growing awareness and acceptance of her lesbian sexuality from her teens through adulthood, and her exploration of the links between psychanalysis and her own emotional and artistic development form one of the most extensive and important psychosexual histories by any writer of the twentieth century. Bishop’s letters to Louise Bradley, her close friend and fellow aspiring writer, written from the age of fourteen through the age of twenty-four, rival the Foster letters in their revelatory power as a window into her early development as a person and a writer.

LOA: Bishop‘s life was unsettled from an early age, setting a pattern for what would be a lifetime on the move. She treats this peripatetic existence in one of her most famous poems, “Questions of Travel,” in which she asks “Should we have stayed at home, / wherever that may be?” Was Bishop ever able to feel truly at home at any point in her life? Was this experience of being always on the outside looking in essential to her art?

Travisano: During her early years with Lota de Macedo Soares at her Brazilian fazenda at Samambaia, from 1951–1960, Bishop had her first experience of something that felt like home. Yet she was living in a foreign country, in the midst of a construction site, while absorbing a new and very different culture in a different hemisphere while seeing “the sun the other way around.” Later, in her condominium at Lewis Wharf overlooking Boston Harbor, she again experienced something like home. In each case, she was in a committed relationship with a supportive female partner. Her time at Samambaia, however, ended in tragedy and her time at Lewis Wharf ended with her unexpected death at 68 from a cerebral aneurysm. She made numerous other attempts at establishing a home, but none of them quite worked out. Paraphrasing Adrienne Rich, one might describe her characteristic stance as that of an outsider in perpetual search for a home.

LOA: You have edited an acclaimed edition of Bishop’s complete correspondence with Robert Lowell and in your new book you write that Bishop’s “sharp and revealing letters . . . are now widely regarded as one of the most brilliant and significant bodies of correspondence of the last century.” What made Bishop such a singular correspondent? Did her letters play a role in her poetry?

Travisano: As a letter writer, Bishop was fluent, funny, gossipy, incisive, anecdotal, observant, self-exploratory—and constantly entertaining. In short, she was a unique and extraordinary verbal performer, and she evoked parallel levels of verbal performance in her fellow correspondents. Bishop’s spontaneous, freely flowing letters offer the perfect counterpoint to her exquisitely crafted poems, which achieve their own sense of spontaneity through the alchemy of art. The roots and sources of many of her greatest poems, including “The Bight,” “Cape Breton,” “At the Fishhouses,” “Questions of Travel,” “The Moose,” and “North Haven” may be traced through a reading of her correspondence.

LOA: Love Unknown is the title of a poem by George Herbert, one of Bishop’s favorites. The phrase works in several ways as a key to the life story you tell, not least as a marker of Bishop’s sexuality. How if at all does Bishop’s lesbianism figure in her work? Is her reticence on the subject a reason why she eschewed the more confessional style of her friend Lowell?

Travisano: Bishop’s lesbianism is absolutely central to her work. Far more than half of her published poems, and even a greater percentage of her posthumously published poems, deal—if only obliquely—with her sexuality, the pressures of hiding it, and the urge to explore or celebrate it. Understanding that Bishop was gay offers vital clues to the meaning of poems as diverse as “The Map,” “Love Lies Sleeping,” “The Weed,” “Paris 7 A.M.,” “Quai d’Orleans,” “Jeronimo’s House,” “Roosters,” “Late Air,” and, and, and. . . . Well, I’m still in her first book. The list could go on and on.

| BISHOP IN LOA |

|

| Elizabeth Bishop: Poems, Prose, & Letters |

LOA: Bishop’s stature seems only to have risen since her death, an ascent that shows no sign of stopping. To what do you attribute her growing appeal with readers, many of whom are discovering her work for the first time?

Travisano: In 1995 I published an essay on this theme: “The Elizabeth Bishop Phenomenon.” The gist of the essay is that all of the cultural factors working against public recognition of her work during her lifetime began to swing around in her favor in the early 1990s. The craze for confessionalism fell out of favor, and readers became more adept as reading texts that were encoded with subversive messages. During her lifetime she had carefully guarded her privacy, which made her poems seem elusive or enigmatic. As we came to know more about her life, her work suddenly seemed far more accessible—and far more self-exploratory. And while she had seemed aloof from the major issues of her day during her lifetime, virtually every important cultural and critical movement of the 1990s has shown Bishop to be, in her own quiet and individualistic way, well ahead of the curve.

These include gender studies, postcolonial studies, global studies, childhood studies, queer theory, genetic criticism, and more. Also, the sheer size, scope, and diversity of her published canon has grown by leaps and bounds. All of these factors have tended to draw readers’ attention to Bishop as a poet, prose writer, and correspondent. And once readers started paying close attention to Bishop’s mastery as an author in these many forms, the steady and seemingly permanent rise in her reputation became assured.

Thomas Travisano is the author of Elizabeth Bishop: Her Artistic Development and Midcentury Quartet: Bishop, Lowell, Jarrell, Berryman. He is principal editor of the acclaimed Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell and served as co-editor of Elizabeth Bishop in the 21st Century and the three-volume New Anthology of American Poetry. Travisano’s work on Love Unknown was supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship and awards from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the American Philosophical Society.