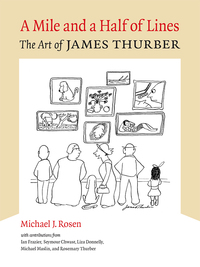

The 125th anniversary of James Thurber’s birth arrives on Sunday, December 8, and this year fans of the legendary humorist have extra reason to celebrate. Launched earlier this fall, A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber is a two-pronged presentation of Thurber’s drawings, both in an exhibition at the Columbus Museum of Art and as a lavish accompanying book by Thurber expert Michael J. Rosen, published by Ohio State University Press.

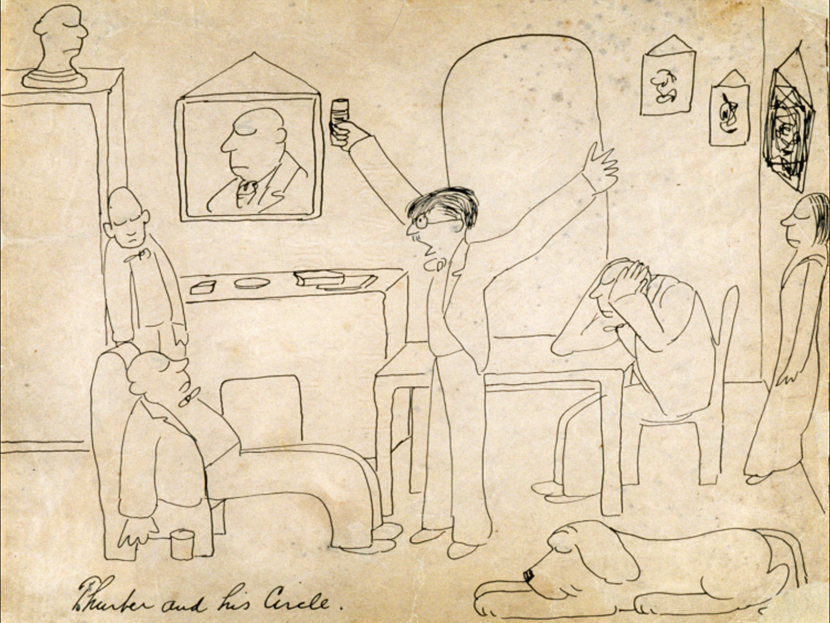

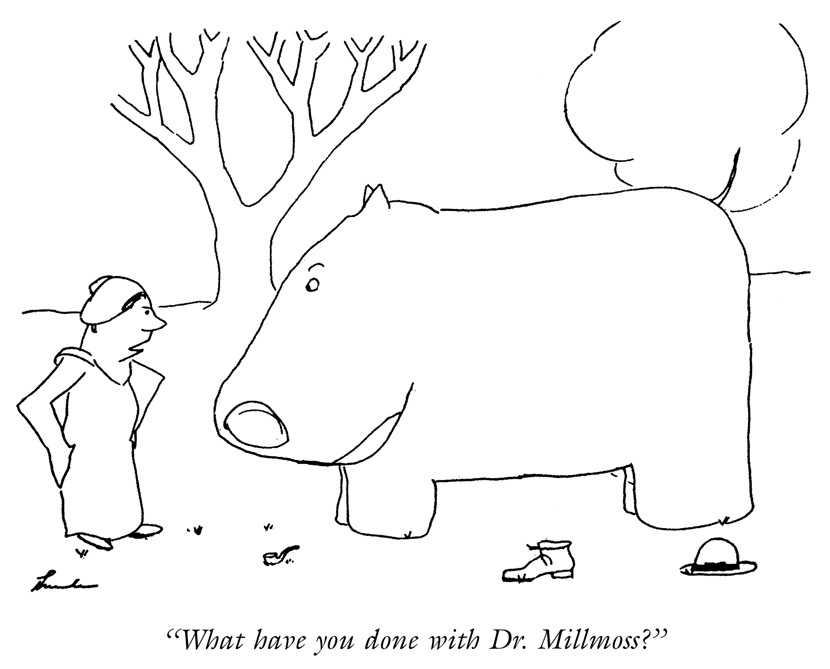

Both the exhibition and the book attest to the validity of Dorothy Parker’s observation that where this artist is concerned, “it is necessary really to show the picture. A Thurber must be seen to be believed.” Accordingly, each iteration of A Mile and a Half of Lines offers a comprehensive tour through the unforgettable Thurber universe. Beloved classics like the seal in the bedroom, Touché!, and What have you done with Dr. Millmoss? are all accounted for, along with a host of less familiar artworks that range from children’s book illustrations and advertisements to doodles he made on the walls of the New Yorker office.

(Library of America readers may especially enjoy the illustrations Thurber did for Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” and Ernest Hemingway’s Green Hills of Africa—the latter of which, once glimpsed, may make it difficult for anyone to think of Hemingway’s hairy-chested hunting opus in quite the same way ever again.)

Thurber’s writing hasn’t lacked for advocates in recent years, what with high-profile media names like Keith Olbermann and Michael McKean lending their support. But as Michael J. Rosen acknowledges in his introduction to A Mile and a Half of Lines, the visual art may have faded somewhat from public consciousness. Rosen consequently pitches the book as a “rallying cry” in which prominent contemporary writers and cartoonists make the case for why Thurber’s art—with its mixture of skewed comic sensibility and rudimentary yet strangely perfect draftsmanship—still has the power to amuse and enchant in the twenty-first century.

Via email, Rosen shared his thoughts on all things Thurber—men, women, and dogs—with Library of America.

|

| A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber by Michael J. Rosen (Ohio State University Press, 2019) |

Library of America: As you note in your introduction, A Mile and a Half of Lines is the first book dedicated to Thurber’s art, and the Columbus Museum of Art show is the first time his art is the subject of a full-scale exhibition. Together, they add up to a major argument for his stature as a visual artist. Why has it taken until now for this to happen?

Michael J. Rosen: To varying degrees, various reasons. First, Thurber never considered himself an artist and never engaged in the art business. While he was part of many group exhibits, and did have several one-person shows in the Thirties and Forties, he had no gallery representation or commitment to “fine art.” He created illustrations for ad agencies. He illustrated friends’ books. But that was the extent of his ambition given that he proclaimed himself to be a writer who agonizes over his words . . . and relaxes by drawing.

His medium, nearly always black ink or pencil, was confined to typing paper, hotel stationery, cardboard, walls, menus—Thurber didn’t think of preserving or archiving his art. And he gave away art like thank-you notes and party favors. The provenance of many of the most popular drawings remains unknown. So the potential curator or art historian is left with a yawning void happily populated by donations from family and friends.

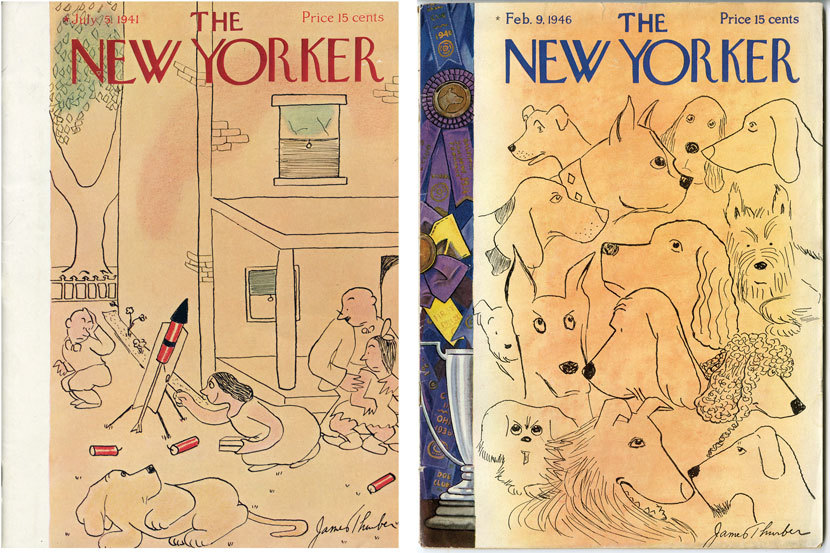

But even more profoundly, it’s key to remember that his entire output as an illustrator or cartoonist lasted a very short time: between his first drawings in The New Yorker in 1927 and the last drawings he was able to do with partial sight in 1941. Yes, he tried a variety of methods to draw larger, in white chalk on black paper, etc., but as Thurber’s artwork burst onto the scene, readers couldn’t get enough of it. And, in a very short time, they couldn’t get any.

LOA: The book and the exhibition make the case that Thurber permanently changed the nature of cartoons in the United States. Just how did he do that?

Rosen: In two ways. First, he drew without training. Without sketching. Without a particular idea in mind. “Pre-intentionalist,” he called it. As the philosopher Karl Kraus noted, words are the mother of thought, not the handmaid. So, too, were Thurber’s spontaneous lines.

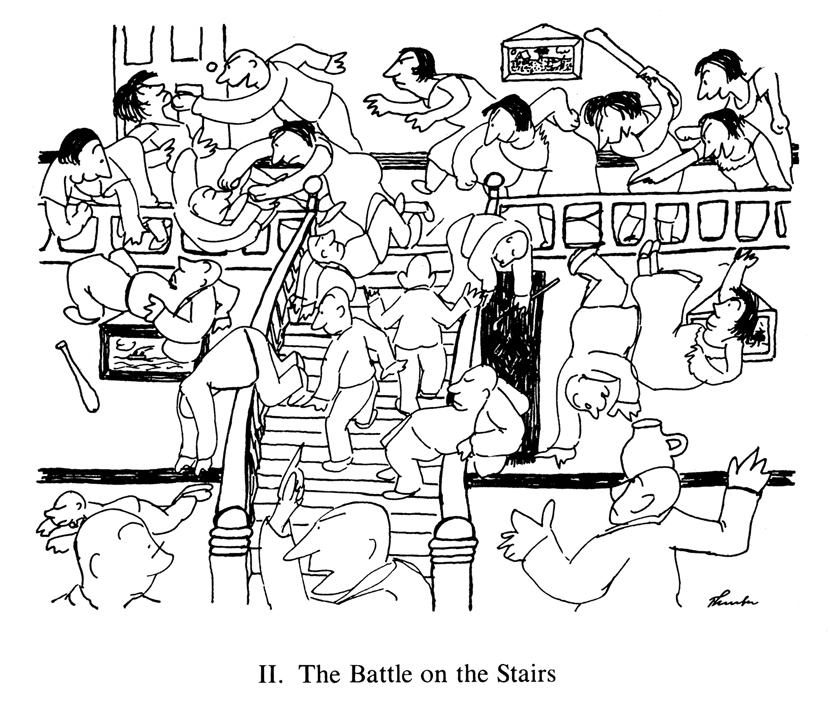

Not only were the few lines scrawled across the page executed in a matter of seconds, the accompanying caption was a part of the problem-solving: his mind at high idle, revved up to resolve the scene as it fell into place. Now, we think nothing of the spontaneous line, the undraftsman-like execution. But his work came as a shock. It was met with contempt, envy, dismissal, derision. But his cartoons were as fundamental a shift as Mark Rothko’s colored canvases, de Kooning’s abstractions, Warhol’s appropriations of common objects, Duchamp’s claiming a snow shovel was art.

Just as profound is the fact that Thurber drew images that were, in and of themselves, funny. Prior to his cartoons, artwork was handsomely drawn, perhaps wryly diverting, but rarely humorous. That was the role of the caption. And, until Thurber, most every caption offered a brief narrative. A snippet of dialogue. An explanation. So a reader/viewer would see the image, nod, read the caption, and come away with a tidy punchline. With Thurber’s cartoons, it was “humor at first sight”—an inexplicable situation, a misfired moment, an unlikely juxtaposition—that was not cinched by the caption, but let run loose . . . straight into the middle . . . or muddle of things.

And I’d claim that’s another reason the work endures and continues to entertain. We’re all still invited into the unlikely happenstance on the page.

LOA: Fraught relations between the sexes are of course a major theme in Thurber’s art. How does this material read in today’s climate? Is it possible that newcomers to his work might not see the humor in the series of sketches he titled “The War Between Men and Women,” for instance?

Rosen: Let’s say “newcomers” are those who come after Thurber’s death in 1961. Haven’t these viewers witnessed or suffered “fraught relations” in ways that Thurber couldn’t have imagined? The sexual liberation of the Sixties. Interracial marriages. Divorce and extramarital affairs and open relationships. The LGBTQ’s ongoing fights for equality and recognition.

So it would be tempting to say that today’s viewers would find something quaint about Thurber’s husbands and wives’ battles. (Battles? As his daughter Rosemary often replies, bafflements!) It’s easy to lose Thurber’s motives or perspective. Jung, Freud, nudism, women’s changing roles, psychiatry, self-help books: Along with enduring two World Wars, the Great Depression, Prohibition, and the dawn of the Machine Age: Thurber’s cartoons roosted in these very realms of discomfort. It’s humor’s stock and trade to take up the plight of fear and mistrust, frustration and outrage.

| *ENTER THURBER’S WORLD* |

|

| James Thurber: Writings and Drawings |

LOA: Summing up what makes Thurber’s best work so distinctive, Wilfred Sheed wrote that “It seemed as though Thurber’s embattled little man had opened the wrong door and stumbled upon a modernist breakthrough”—and in fact modernists across disciplines, like T. S. Eliot and the British painter Paul Nash, were avowed Thurber fans. What was it in these dashed-off drawings that they were responding to?

Rosen: Permit me a broader ramble for a moment. Velcro, microwaves, saccharine, penicillin, Viagra, superglue—these are all happy accidents—results the “inventor” never intended—that have changed our lives. Some more than others.

And look how we have grown accustomed to life with such breakthroughs. We hardly think twice about Teflon, pacemakers, Play-Doh, or X-rays. (More accidents.)

James Thurber intended to draw a rock upon which a seal was to be resting, but the perspective was off, so he quickly turned it into a bedstead. Two quickly drawn people and two pillows later, a caption read: “All right, have it your way, you heard a seal bark.”

Thurber started a drawing of men gathered at a bar, but one’s head was accidentally drawn a bit too high and small. Rather than including a nine-foot drinking companion, Thurber drew another man shouldering the other gent between the knees. And, as he comments, in a matter of thirty seconds, a caption arrived: “For the last time—you and your horsie get away from me and stay away!”

Many of Thurber’s cartoons, by his own admission, were happy accidents. The “scrawls” before the idea. The picture before the punchline.

Ah, but, as Louie Pasteur notes, “Chance favors the prepared mind.”

Thurber was no trained plein air painter. He didn’t painstakingly create representations of real life. No, Thurber was a plain-old draw-er, recording from really?, not reality. His cartoons show us as the deer in the headlights we are, at the wrong place and the wrong time, befuddled by both the rock and the hard place. Profoundly sensitive to the intrusions and confusions of the era, Thurber’s deft (some would say “daft”) lines were pearls encasing the irritating grittiness of life.

Back to Pasteur. His discovery of vaccines was taken up by the field of medicine and, today, our lives depend on all the uses of his happy accident. And I say it’s no small leap to believe that Thurber’s art—initially accidents but, surely along the way, intentional acts—provided an antidote to the mental state in which his generation persevered. Nash and Eliot, as well as humorists and writers and cartoonists today, have taken up Thurber’s inventions and our lives depend on what his happy accidents have provided.

LOA: Over the years Thurber’s famous dogs have prompted no end of speculation, praise, and wonder, plain and simple. Given your long involvement with all things Thurber, would you like to share any observations on the role dogs play in his art?

Rosen: Many works in Thurber’s canon—children’s books, cartoon collections, memories, essays, stories, and, to be sure, his inimitable fables—frequently focus on other creatures that share our world. Real or imaginary, domestic or wild, the animal kingdom offered Thurber a sort of pastoral for his overly complicated times. Animals exhibit grace and clarity and beauty . . . uncompromised by the human “gift” of reason. So his creatures—the unique breed, “the Thurber hybrid,” in particular—present a cooler perspective on the whirlwind in which we find—or have lost—ourselves.

At first, Thurber used that dog to balance a composition: lamp on one side of the couch, hound dog on the other. But increasingly he saw that the presence of the dog, mostly non-participatory, was offering a calmer, steadier focus on the whole. Serenity. A signpost. A reality check.

And the dog—at least the dog’s head—was an image he could draw from memory until his last days . . . a contour line that his wife or daughter would finish by “dotting” the eye.

Writer, illustrator, and editor Michael J. Rosen has collaborated with the Thurber Estate and written about the works of James Thurber for almost forty years. The founding literary director of the Thurber House in Columbus, Ohio, he has edited six volumes of Thurber’s work, the most recent of which was the Collected Fables (Harper Perennial, 2019), and oversees jamesthurber.org, the official (and comprehensive) website dedicated to the writer and artist.

A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber is on view at the Columbus Museum of Art in Columbus, Ohio, through March 15, 2020. Visit the museum website for complete exhibition details.

Works from A Mile and a Half of Lines: The Art of James Thurber, published by Ohio State University Press, are copyright © 2019 by Rosemary A. Thurber. Reprinted by permission of Rosemary A. Thurber and the Barbara Hogenson Agency, Inc. Drawings courtesy Ohio State University Libraries.