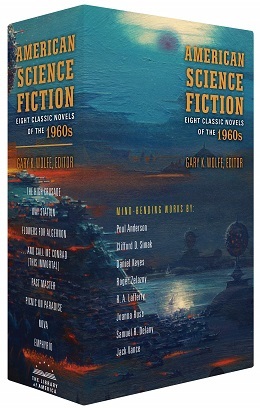

Library of America deepens and extends its commitment to classic science fiction this fall with the release of American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, a two-volume set edited by Gary K. Wolfe.

Readers may remember that back in 2012 Wolfe edited the two-volume survey American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s for Library of America. In the new collection, he brings together eight novels that embody all the creative intensities of a decade that was every bit as a tumultuous and transformative for science fiction as it was for society at large.

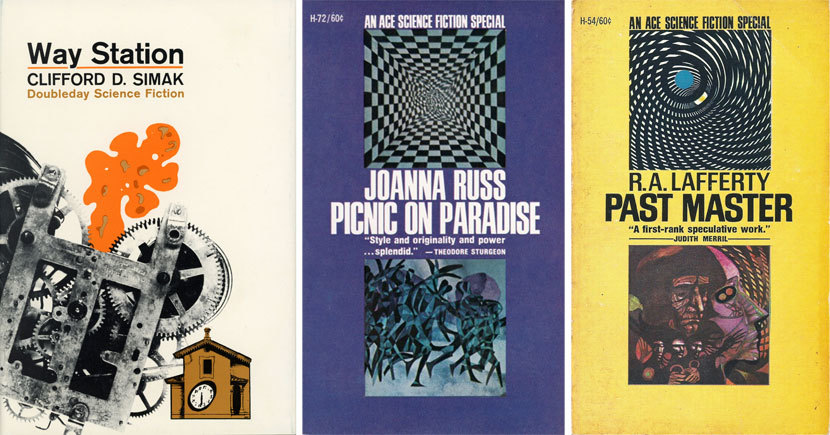

The first volume, American Science Fiction: Four Classic Novels 1960-1966, includes Poul Anderson’s madcap novel set in medieval England, The High Crusade (1960); Clifford D. Simak’s Hugo Award–winning Way Station (1963), Daniel Keyes’s beloved Flowers for Algernon (1966); and Roger Zelazny’s postapocalyptic thriller This Immortal (1966), published here under the author’s preferred title, . . . And Call Me Conrad.

American Science Fiction: Four Classic Novels 1968–1969, the companion volume, consists of Joanna Russ’s pioneering work of feminist SF, Picnic on Paradise (1968); Samuel R. Delany’s proto-cyberpunk space opera Nova (1968); R.A. Lafferty’s quirky, neglected, utterly original debut, Past Master (1968); and Jack Vance’s haunting Emphyrio (1969).

Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and the author, most recently, of Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature and Sightings: Reviews 2002–2006. He writes regular review columns for Locus magazine and the Chicago Tribune, and co-hosts the Hugo-nominated Coode Street Podcast with Jonathan Strahan. Via email, he talked to us about the tough choices he had to make for the new collection, the idiosyncrasies of the authors represented, and why these particular novels have endured for more than fifty years.

Library of America: Let’s say I’m an avid science fiction fan from 1960, and I’m teleported a decade ahead, to 1970. What would be most apparent to me about the ways the genre had evolved in those ten years?

Gary K. Wolfe: Well, if you were so inclined, you could take some comfort in seeing that favorite authors from the 1950s and earlier—Robert A. Heinlein, Poul Anderson, Clifford Simak, Arthur C. Clarke, Andre Norton, Fritz Leiber, Theodore Sturgeon, and many others—were still producing major work. But two of the prestigious Hugo Awards in 1970 went to authors unknown in 1960—Ursula K. Le Guin and Samuel R. Delany. And the Nebula Awards, voted on by the writers themselves, hadn’t even existed in 1960. The nominees in 1970 included plenty of new names—Joanna Russ, R. A. Lafferty, Thomas M. Disch, Kate Wilhelm, Gene Wolfe.

These new writers often alluded to earlier science fiction traditions such as space opera, alien invasion, planetary adventure, but sometimes with a good deal of irony and almost always with a new sense of style, character, and even worldview. This new sense had become something of a mission with the New Wave, characterized in England by Michael Moorcock’s editorship of New Worlds magazine and in the U.S. by Harlan Ellison’s massive anthologies Dangerous Visions in 1967 and Again, Dangerous Visions in 1972.

But science fiction had gained traction in other parts of the culture as well. In 1960, The Twilight Zone, which seemed to represent the first effort toward adult science fiction in network television, was still in its first season. By 1970 it had come and gone, and so had Star Trek—but they both spawned franchises that are still lively a half-century later. A science fiction movie fan in 1960 might have become resigned to endless rubber-suit monster movies, but by 1970 we had seen a genuinely philosophical film by a major director, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and another film from a science fiction novel, Charly (based on Daniel Keyes’s Flowers for Algernon), had won a Best Actor Oscar—something that would have been unthinkable in 1960.

LOA: Flowers for Algernon is in some ways the best-known novel in the set—it has sold millions of copies and inspired Charly in 1968—and also the most surprising, because many readers may be surprised to see it considered science fiction at all. Is it an anomaly in the genre?

Wolfe: I’ve seen the same reaction from students when I have taught Flowers for Algernon in my college classes, and their main argument seemed to be that since the novel focused on the character arc of Charly Gordon rather than on futuristic technology, it was somehow a real real novel and not science fiction. And indeed, Keyes wasn’t much interested in the science behind the brain surgery that enabled Charly’s transformation. But transformation had long been a central theme of science fiction—people become invisible, gain superpowers, develop telepathy, or even vastly increase their intelligence (Poul Anderson’s Brain Wave, from 1953, is an example of the latter).

And as Daniel Keyes made clear in his memoir of writing the book, Algernon, Charly, and Me, he was clearly part of the science fiction community when he was writing the story, and the first markets he wanted to sell it to were the science fiction magazines; it first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction after the editor of Galaxy had insisted on a happier ending. The story became one of the most widely anthologized in the history of science fiction, sometimes even in textbook anthologies, and the novel stayed in print continuously, no doubt helped by the popularity of the film. So I suspect that many readers encountered the story or novel not as an example of character-based science fiction, but simply as a tragic tale of a disabled young man who gets a chance to become “normal,” but learns there are unanticipated consequences—another classic science fiction theme.

LOA: A newcomer might be struck by how the four novels in Volume Two all come from a span of less than a year and a half, 1968–1969. Was there a kind of accelerated or heightened creative ferment in science fiction as the Sixties barreled toward their conclusion?

Wolfe: It certainly seemed that change was accelerating, not only in science fiction but in terms of historical events that seemed science fictional in scope; after all, the Democratic convention riots, the moon landing, and the Woodstock music festival all happened within that twelve-month period.

Actually, we could easily have filled up both volumes from these two years alone. It turned out to be fortunate that Library of America had already published novels from this period by Ursula K. Le Guin, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and Philip K. Dick, and it’s important to view American Science Fiction in the context of those separate volumes. 1968 saw Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? as well as major novels by Thomas M. Disch, Alexei Panshin, Clifford Simak and others, while 1969 saw both Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness and Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse–Five, along with important work by Piers Anthony, Harry Harrison, Anne McCaffrey, Norman Spinrad, and Robert Silverberg.

Silverberg in particular is an interesting example regarding this late 1960s flowering. He’d been a prolific writer of short fiction during the 1950s, but after the partial collapse of the magazine market late in that decade had turned somewhat towards other kinds of writing. But, perhaps influenced by editors like Moorcock and Ellison, but also Terry Carr and Frederik Pohl, science fiction became more welcoming to literary or experimental fiction, and Silverberg responded with increasingly sophisticated work, such as Dying Inside (1972). He would certainly be included in a 1970s collection, should there be one.

As the 1960s progressed, the influence of these important editors became more and more evident, and many writers, like Silverberg, may have felt that the old chains were off, and they were free to try newer things. Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, which appeared in 1974, seemed like a much more radical literary experiment than most earlier science fiction, and even old hands like Robert Heinlein tried out newer forms of narrative. This was increasingly evident from the mid-1960s onward, but by 1968 and 1969 it had begun to reach its peak.

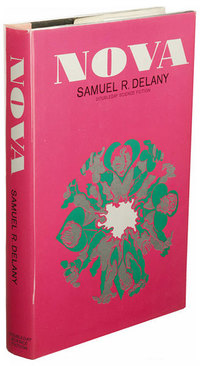

LOA: Appreciations of Delany’s Nova regularly note that it has roots in old-fashioned space opera, and in the next sentence mention how it anticipates cyberpunk. How does Nova simultaneously evoke science fiction’s past and anticipate its future?

Wolfe: As his own critical and autobiographical works make clear, Delany was a sophisticated and critical reader of science fiction from an early age, so it’s not surprising he would make use of his knowledge of the genre’s classic space opera tropes, just as he had made use of the post-nuclear apocalypse theme in The Jewels of Aptor or the generation starship theme in The Ballad of Beta-2. So while the huge planet-hopping canvas and the economic and corporate rivalries suggest classic space opera, the characters are quite different. While there are human-machine interfaces and implants in Nova, I think the more important way in which it anticipates cyberpunk has to do with these characters: racially diverse, often alienated outsiders like The Mouse or drifters like Dan.

Nova is set in a much more distant future—the thirty-second century—than novels like William Gibson’s Neuromancer, set in the reasonably near future, probably sometime in the twenty-first century. And while Nova does touch upon themes like body modifications and virtual reality, it’s less concerned with information technology, urbanization, and other earmarks of cyberpunk. But I’ve always felt that, despite the remarkable futuristic insights of Gibson, Sterling, Rucker, and others, the “punk” aspect of cyberpunk is what really gave rise to all the later variations like steampunk, dieselpunk, etc.—and that streetwise “punk” sensibility was certainly prefigured by Nova, along with a few other important works of the ’50s through the ’70s.

LOA: The new LOA anthology includes Joanna Russ’s debut novel, Picnic on Paradise, and arrives right on the heels of a major new critical study of Joanna Russ by Gwyneth Jones. Reviewing that book last month, Roz Kaveney suggested that Russ has suffered from “comparative neglect” until now—do you agree? And why might the culture in 2019 be more receptive to Russ’s work than it had been previously?

Wolfe: Thanks for mentioning the Gwyneth Jones study of Joanna Russ, which is part of the Modern Masters of Science Fiction series which, wearing another hat, I edit for the University of Illinois Press. Russ was one of the first authors I wanted to see covered in these monographs, not because I felt she was neglected, but because she wasn’t as widely read as she should be—which isn’t quite the same thing.

In her book, Jones describes Russ’s last public interview, which was conducted by phone with Samuel R. Delany at the feminist science fiction convention Wiscon in 2006. I was in the audience then, and it seemed that the mostly young listeners knew Russ’s reputation far more than they knew her fiction. Her nonfiction work, such as How to Suppress Women’s Writing, To Write Like a Woman, and What are We Fighting For? seems to find its way into the hands of each new generation of readers, and I regularly come across someone who has just discovered, and often been astonished by, her classic 1975 novel The Female Man. So it may be that Russ’s approach to feminism—direct, witty, uncompromising, often angry—is more aligned with contemporary attitudes than it was with the attitudes of the 1960s and 1970s.

But its feminism wasn’t the only reason we selected Picnic on Paradise. Russ was a first-rate science fiction writer purely on science fiction’s own terms, and her stories about Alyx—of which _Picnic on Paradise is the only novel—played with elements of genre in a way that is much more common now than in the 1960s. Elements of sword and sorcery fantasy mix with elements of planetary romance and time travel in a way that seems to prefigure much of the genre-bending speculative fiction that is being written now, and in that sense Russ’s work might seem even more relevant today than in its own time.

LOA: In his introduction to the separate Library of America paperback edition of R. A. Lafferty’s Past Master, which is also included in the anthology, Lafferty scholar Andrew Ferguson teases out a fascinating ecological theme that may resonate more for readers today than it did in 1968. Will we always be finding new ways to read Lafferty, an unclassifiable maverick even in this company?

Wolfe: It seemed clear from the original reviews of Past Master—most of which were in science fiction magazines—that indeed Lafferty seemed an unclassifiable eccentric even in the context of 1960s New Wave science fiction. But he has been consistently building a following over the decades, and one indication of how his work resonates with a wide variety of contemporary readers is The Best of R. A. Lafferty, published earlier this year by Gollancz in England. Each story is introduced by a different Lafferty enthusiast, and the contributors include Neil Gaiman, Michael Dirda, Andy Duncan, Robert Silverberg, Connie Willis, Samuel R. Delany, John Scalzi, Jeff VanderMeer, and Patton Oswalt, as well as younger writers like Gwenda Bond and Kelly Robson.

I think Lafferty will eventually be recognized as one of the great American eccentric writers, although his peculiar tall-tale style may be more evident in his short fiction, a fair amount of which remains unpublished, as Andrew Ferguson discovered in his research. Past Master has some of that tone, but also demonstrates Lafferty’s more serious philosophical concerns, his intellectual breadth, his deep Catholicism, and his terrific sense of irony.

LOA: Three of the authors included in the new anthology—Clifford D. Simak, Poul Anderson, and Jack Vance—had well-established reputations long before the 1960s. Was their inclusion an effort to recognize an older tradition in science fiction, or did they really contribute to the major changes in the field during that decade?

Wolfe: I certainly wanted to establish some sense of continuity with the earlier 1950s collection, but there were other reasons as well. Not all of the relevant and exciting science fiction is the work of sparkling new writers; there’s something to be said for veterans who have honed their skills over decades. In Simak’s case, it’s true that he published his first story as far back as 1931, but it’s also worth remembering that he won a Hugo and Nebula as late as 1981. And in its own modest way, his voice is almost as unique as Lafferty’s; he pioneered a kind of pastoral science fiction, distinctly Midwestern in flavor, but quite unlike that of his fellow Midwesterner Ray Bradbury. I thought that rather gentle tradition, still very much alive, was important to represent along with the stylistic bells and whistles of the 1960s.

Simak, like Vance (who began publishing in 1945) and Anderson (1947), benefitted from the opening up of the novel market to science fiction writers in the 1950s. All had written popular story series, such as Vance’s very influential “Dying Earth” tales, Simak’s “City” stories, or Anderson’s Time Patrol series, and all had taken advantage of the chance to develop their novel-writing skills.

It’s interesting to note that all of the Hugo Awards won by these veteran writers were won in the 1960s or later. The notion that earlier traditions of science fiction are suddenly overturned or replaced by new generations of writers is at best an oversimplification. The genre has attained the diversity it now enjoys by a process more of accretion than revolution. The older traditions remain, and sometimes, as in the case of space opera or time travel, they even serve to reinvigorate the newer writers with the challenge of reimagining classic themes.