Just published by Library of America, The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life collects thirty-two essays about Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts—the comic strip that ran daily for half a century and whose iconic status in American culture remains undiminished nearly twenty years after the end of its run in 2000.

|

| The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life |

Ranging from distinguished literary names like Umberto Eco, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Ann Patchett to contemporary comics masters Seth and Chris Ware, the contributors reflect on the experience of discovering Schulz’s work as a child, their identification with its characters and predicaments, and, for the artists in the book, the momentous effects of their encounters with the strip on their later careers. Taken together, the essays and comics of The Peanuts Papers form a varied, entertaining, and poignant set of responses to a cultural phenomenon whose like we may never see again.

The collection’s editor is Andrew Blauner, who has edited six previous anthologies, including, most recently, In Their Lives: Great Writers on Great Beatles Songs (2017), and is the co-editor, with Lee Gutkind, of For the Love of Baseball (2014). Blauner has been published in The New York Times, is a member of PEN American Center and the National Book Critics Circle, and founded Blauner Books Literary Agency in 1995. Via email, he answered our questions about compiling The Peanuts Papers and his ambitions for the book.

Library of America: The Peanuts Papers assembles an impressive and notably eclectic group of contributors. How did the roster come together?

Andrew Blauner: The word “anthology” comes from the Latin word, loosely translated, for “bouquet.” I wanted this book to be that. A love letter, really, to Peanuts. But in order for it to work, it needed a tapestry of voices, the apprehension being that it might end up—what’s the word?—homogenous, monotonous.

So, in terms of how, then, the roster came together, I reckon that I started with the archival material that I wanted to include, the pieces by Sarah Boxer, Umberto Eco, Jonathan Franzen, Maxine Hong Kingston. George Saunders. And built out from there. Some, such as Gerald Early, Adam Gopnik, and Rick Moody, have become sort of go-to people for me, as they have so much to say that’s interesting that I’d go to them for a collection on almost any subject. They always deliver, never disappoint.

Then, there was a conscious thought and effort to go to some cartoonists/illustrators who write well in addition to drawing. One of the quirks of the book is that I never intended for there to be any actual Peanuts strips in it, in part because readers see the iconic touchstones in their minds’ eyes—Linus’s blanket, Charlie Brown’s shirt, Snoopy’s doghouse, Schroeder’s piano, Pigpen’s cloud—and I liked the challenge, if there was one, the gauntlet, for the contributors to write about Peanuts without using those actual visuals. Anyway, putting the premium on including cartoonists yielded the great fortune of getting Hillary Campbell Fitzgerald, Chris Ware, Seth. . . .

I liked the idea of including some great writers, known primarily as fiction writers, so we have Ann Patchett and Mona Simpson. Then there was another group whom I went to thinking that there might be a piece on a specific aspect of Peanuts that I’d like them to write—for example, Peter Kramer on Lucy and psychiatry, Jennifer Finney Boylan on “Outsiders.” There are two poems in the book, one by Jill Bialosky and one by Jonathan Lethem, in part because there is a certain poetry to the strip. And also, there were cases when I invited one person to contribute and that person suggested someone else, who turned out to be a terrific addition—for example, Susan Cheever led me to Clifford Thompson.

LOA: In his essay here, Chuck Klosterman seems to get at something essential when he defines Peanuts as “an introduction to adult problems, explained by children.” Were you surprised by the range of grown-up, and in some cases very contemporary, concerns—depression, narcissism, and gender identity, among others—that Peanuts elicits from many of these writers?

Blauner: Yes, that is a resonant turn-of-phrase, in Chuck’s excellent piece. And to answer your question, in a word, no. There is probably some positive correlation between how well, how deeply, one knows the strip, and how surprising that would be. Peanuts was a strip—as I understand it, in part thanks to Chris Ware’s piece and a history lesson there—originally conceived by Schulz to be for grown-ups, really, and not just kids. Ironic, maybe, to some, since there are virtually no adults in Peanuts.

Perhaps part of the secret of the appeal of Peanuts is that Schulz’s children had authentic and identifiable anxieties, doubts, fears, insecurities. The characters expressed disarming, endearing and universal vulnerabilities. And we connect with, relate to that, in very personal ways.

Peanuts is at core about friendship and love, loneliness and losing, hope and happiness, faith and frustration. It embraces faith, hope, optimism in the face of adversity, cynicism. It’s about the truth, the truths of life—sometimes discomfiting truths—and children telling other children the truth. It’s so much about what it is to be alone, small, vulnerable, isn’t it? In other words, human.

LOA: To delve into these pages is to be reminded of what a polarizing figure Snoopy became among Peanuts fans. Why does a cartoon beagle provoke such divided reactions? (Do you want to declare your own allegiances?)

Blauner: Who knew?! Not me. Until I worked on this project, I had no idea how polarizing Snoopy can be. (On the other hand, I was pleasantly surprised to discover just how much affection, admiration, compassion is out there for good ol’ Charlie Brown.) Anyway, Sarah Boxer writes insightfully about Snoopy’s so-called narcissism. Daniel Mendelsohn—not in the book—has a whole rant, I think, against Snoopy. Je refuse! Personally, I love Snoopy, always did, and always will. And now my son does. Snoopy doesn’t speak, but he expresses so much, and embodies so much, so much that is joyful, independent. But he’s also a writer. And we see him suffer for that craft. . . . Snoopy Forever.

LOA: Charles M. Schulz died nearly twenty years ago, on February 12, 2000, and the last original Peanuts Sunday strip ran the following day. And yet his great creation remains ubiquitous, a touchstone for so many. Is any creative work in twenty-first-century American life likely to play such a central role in the culture?

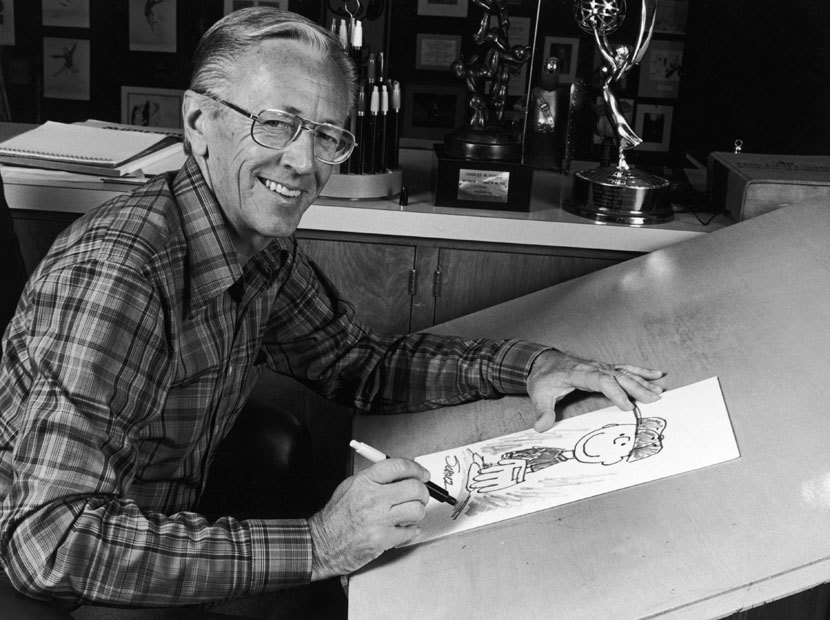

Blauner: That really bordered on something mystical, didn’t it? Schulz had long said that most anything he had to say he said through the strip, through his characters. Schulz and Peanuts are inextricably linked; he was the strip and the strip was him. So, the fact that he died within twenty-four hours of the publication of the last strip, well, you decide. . . .

Yes, Peanuts is as ubiquitous as ever if not more than ever, be it through the strip itself, still running in papers as prominent as The Washington Post, the beloved holiday specials from Halloween to Christmas, Apple TV launching a new Peanuts show and Snoopy in Space. Come the start of 2020, there will be a new national tour of the theatrical production You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, THE most produced musical in history, including, of course, school productions, now at approximately 40,000, with over 250,000 people having been in those productions.

In an era hauntingly reminiscent of the Gilded Age, it’s axiomatic that we live in a highly polarized culture. The idea of enduring cultural consensus about almost anything seems, as someone at LOA put it, “an exercise in wistful nostalgia.” And yet. . .

And yet, it’s been suggested that Peanuts may be the final example of a great American work of art loved broadly and without reservations by the masses, the elite, and everyone in the so-called middle. Peanuts ranges freely across the ideological spectrum in ways that one is hard-pressed to find anywhere else. Presidents Barack Obama and Ronald Reagan are both on record as fans. Schulz was reportedly a life-long Republican, yet his son Monte has said that one of his father’s great regrets was not voting for Kennedy.

What could rival Peanuts as a kind of secular Bible, a chapter-and-verse touchstone? Peanuts possesses and projects a critical, palpable, uncanny, if not altogether unique sense of humanity and humility.