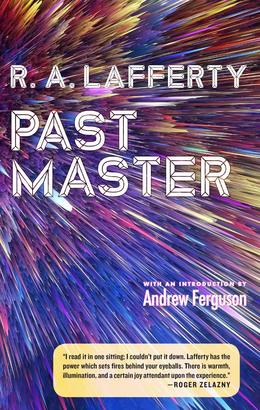

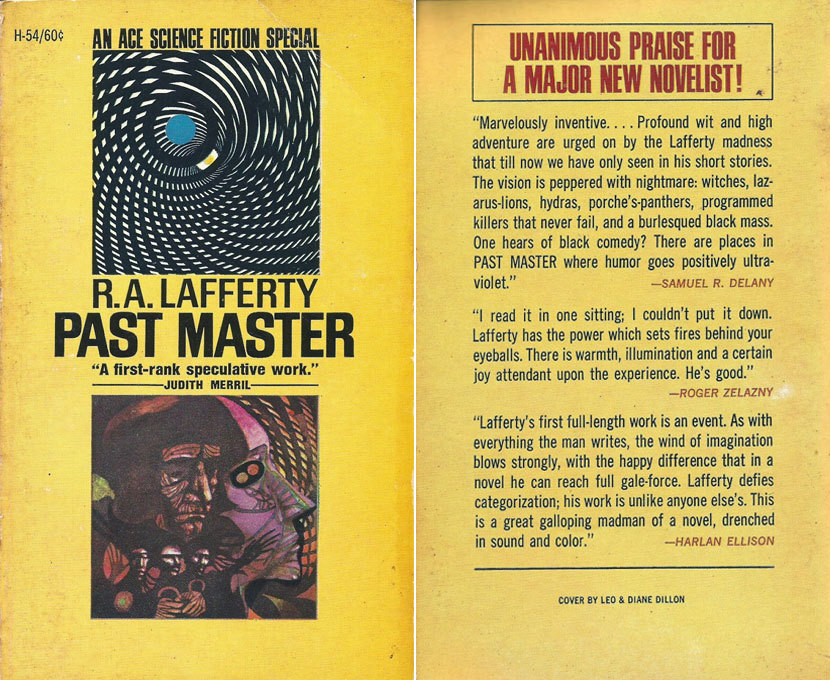

This fall, Library of America reissues R. A. Lafferty’s 1968 debut novel Past Master in two formats: Within the two-volume anthology American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, edited by Gary K. Wolfe, and in a standalone paperback edition with a new introduction by the Lafferty expert Andrew Ferguson. In the following excerpt from that essay, Ferguson offers a biographical sketch of Lafferty and suggests why Past Master “serves as an excellent introduction to the work of a writer who . . . will show you a new vantage point on this world and all the new worlds that may yet come.”

By Andrew Ferguson

In this essay I am tasked with something at once simple and impossible. That task: to introduce Lafferty’s Past Master, a work that does not brook introduction. So I say, go read Past Master! And for those of you who do so immediately, the simple part of my task is done. Only for the rest of you does the impossible remain.

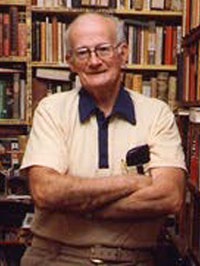

Well then, if Past Master is impossible to introduce, R. A. Lafferty is somewhat less so; let us start there. Lafferty’s was a remarkably unremarkable life. Vacations and military service aside, he spent almost all his days in Tulsa, Oklahoma, working more or less the same job at the same store counter, selling parts to electrical engineers and contractors. He never married, never had kids, never earned a college degree. During the Second World War, he saw action in the South Pacific, but apart from a few oblique references in obscure stories, he left no record of those years. Every day he went to mass, took a walk round his neighborhood, and settled in to read, watch TV, or work a little bit on his foremost hobby, the learning of languages. And then he also wrote some of the wildest, funniest, most outlandish stories ever seen in science fiction, fantasy, or whatever other genre category you’re brave enough to place him in. (Far better writers than I have thrown up their hands at this task: Theodore Sturgeon once imagined that future literary historians would simply label his works “lafferties.”)

Though Lafferty is best known today—when he is known at all—as an author of science fiction, this was as much historical accident as purposeful career choice. When he picked up writing as a hobby in the late 1950s, ostensibly as a way to fill the hours while “cutting down on drinking and fooling around,” he experimented with a variety of genres then popular on newsstands: hard-boiled detective fiction, men’s own adventures, slice-of-life domestic tales. Though he placed a handful with small-circulation literary magazines—starting with “The Wagons” in the New Mexico Quarterly—they sold poorly enough that he shelved most of them to concentrate on the one area in which he had more consistent success: science fiction. Perhaps if that field hadn’t been on the verge of its own stylistic revolution—the “New Wave,” as it was called largely in retrospect, borrowing not just the name but also the attitude, the techniques, and a host of preoccupations from French cinema—then Lafferty would have struck out there as well. But he met science fiction at a time when it was desperate for new voices and new directions, and his style—equal parts carnival barker, bar-stool raconteur, and apocalyptic prophet—was met with an eager embrace.

By the time he began publishing in SF, he was already in his mid-forties, unusual in a field where many writers cut their teeth in their teens. His tales, by turns philosophical and playful, humorous and horrific, often all within the same piece, sold steadily: he featured in many of the best outlets in science fiction, including Frederik Pohl’s (and later Ejler Jakobsson’s) Galaxy, Robert Silverberg’s New Dimensions, Terry Carr’s Universe, Damon Knight’s Orbit, and of course Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions. At one time or another he counted among his admirers Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel Delany, Roger Zelazny, Judith Merril, and Gene Wolfe. Lafferty’s stories won him, in addition to an audience, the 1973 Hugo Award for Best Short Story; many of his best were collected in the volumes Nine Hundred Grandmothers, Strange Doings, Does Anybody Else Have Something Further to Add?, and others that may be found in this book’s biographical note (they will, however, be much tougher to find on the shelves of your local bookstore). A rather easier-to-find volume, the thick Best of compilation published in early 2019 by Gollancz, offers twenty selections handpicked by authors who love them; the complete stories are being gathered for collectors by Centipede Press with an eye toward wider distribution down the line. While far from common commodities, Lafferty’s stories do still circulate, likely more today than over the past few decades. To read any of them is to at least consider the possibility that he did become, as he once asserted, “the best short story writer in the world” (in Patti Perret, The Faces of Science Fiction, 1978).

The novels are a rather different matter. Although several of them were also nominated for genre awards, they have always appealed to an even more niche audience, a niche within a niche. If the stories break many of the “rules” of writing—and they do, departing sharply at times from conventions of characterization, pacing, and plot—then they do so at a manageable length. The novels tend to sprawl, binding together episodes less through elegant plot mechanics than via other logics that are not always immediately evident. But though the novels ask much more of a reader, the rewards are consequently greater: a series of windows opened on one of the most idiosyncratic imaginations American fiction has ever seen.

Any science fiction that ceases to speak to the present moment, no matter the year of its publication, is already on the way to becoming the province of genre hounds and antiquarians. Past Master is unavoidably a product and reflection of its times: a response to what Lafferty perceives—likely in the wake of LBJ’s Great Society initiatives—as renewed support in society and popular culture for the idea of Utopia; this he considered as bad as dystopia, if it were possible even to tell the two apart. Lafferty’s Thomas More is wise to this fact, which is why his Utopia can only be construed as searing satire: an image of a world pleasant enough on its surface, but hellish to endure even if (perhaps especially if) one is a member of the privileged class with the full rights of citizenship, rather than one of the numerous slaves or nearby foreigners whose lives the Utopians “improve” by force.

As you might imagine, Lafferty’s own politics were in a class of their own; he referred to himself at times as the lone member of the “Centrist Party” without meaning anything like what we mean by that term today. But the thrust of this book is nonetheless a conservative one (even as he would, on etymological grounds, reject that term “conservative”): the revolutionary energies here are intent on preserving the Church and overthrowing an order that promises material equality, even luxury, at the cost of the soul (“the only one of the four-letter Anglo-Saxon words really out of fashion on Astrobe,” as Lafferty has Thomas say in the short-story draft). Lafferty’s targets are so diffuse as to include basically everyone; as the clockwork mass shows, the Church itself—still finding its shape after the changes of the Second Vatican Council, which Lafferty deplored—is certainly not exempt. But in the decades since, all those targets have shifted: today’s pre-Vatican II Catholics have an entirely different set of axes to grind, and I suspect Lafferty would not care for the SF to which they are drawn. Similarly, today’s most strident conservatives espouse a gospel of material prosperity for its own sake that is closer to the soulless Astrobe Dream than any of the revolutionary platforms aiming to blunt the edges of our society’s prevailing inequalities. At one point in the book, Kingmaker warns Thomas not to try to set policy because “Politics on Astrobe has become an intricate science.” To Thomas’s rejoinder that politics was intricate in his own time, Kingmaker can only laugh; fifty years on, our sympathies might well now be with him.

Still, if the foregoing decades of cultural shifts mean that Lafferty’s occasional political satire no longer cuts as deep as it once might, there are other elements in Past Master that have come more strongly to the fore—in particular, the ecocritical or even “ecomonstrous” aspects of the work. The latter term, a coinage by Lafferty scholar Daniel Otto Jack Petersen, describes the ways in which monstrosity is mapped onto the environment—not merely as compensation for and irruption of repressed psychological factors, though there’s plenty of that here too (see for instance the nightmare banned from the cities by group therapy that reappears as physical fact and, later, stock animal in the Feral Lands), but also in the wider sense of an encounter with the natural world and the nonhuman more generally “as aesthetically evoked in fiction through such monstrous modes.”

Astrobe’s wildernesses are “the psychic power-house” of the planet, filled to overflowing with terrifying libidinal energy. They have “no close Earth equivalent”; though they resemble “certain Earth rain-forests” and sustain astonishing biodiversity, they are neither picturesque nor paradisiac: fearsome rouks and “twenty other species of creatures” in the Feral Lands are “capable of slicing up a man and eating him.” This portion of the novel is often left out of summaries and descriptions of it, and it isn’t present in his short-story draft—strangely, for in book and planet alike, the Feral Lands cannot be eliminated or even much regulated without throwing off the balance of plant and animal life, and perhaps ruining the resources on which the cities of golden Astrobe depend. In fact, from the ecomonstrous point of view,

the civilized world of Astrobe is really of no consequence. . . . It is a but a thin yellow fungus growing on a part of the hide of the planet. Should this shaggy orb shiver its hide uncommonly but once, the Golden Astrobe civilization would be destroyed instantly.

All the accomplishments of the Utopian architects, all the pinnacles to which they have pushed humanity (or pushed humanity off of), are as nothing in the face of deeper ecological might. Even the great Nothingness, Ouden itself, is stalemated in the encounter with the nonhuman: the same “intense flashes of insane lightning” that reveal Ouden’s face stamped on the very sky of the world also enable Thomas to escape certain death on the mountaintop. No wonder then that it is during his encounters in the Feral Lands, and with the people whose lives have been shaped by the struggle for survival there, that Thomas first begins to question his initial embrace of the Astrobe Dream. And no wonder either that this ecocritical ethos resonates more strongly today, as new terrors daily attest to the great cost and fragility of our own accomplishments, than it did for critics back in 1968 when the U.S. environmental movement was only beginning to emerge.

So where then does Past Master fit into Lafferty’s work and legacy? For the former, it builds out the semiconsistent universe of his off-world stories, in which Astrobe takes its place among other planets such as Camiroi, Klepsis, Aranea, Hokey Planet, and so on; it also, through the unlikely figure of Thomas More, provides a bridge to the complex, spiritually unsteady protagonists of other Lafferty novels: Hannali Innominee in Okla Hannali; Dana Coscuin in The Flame Is Green; Finnegan in Archipelago, The Devil Is Dead, and elsewhere. For the latter, his legacy, Past Master brings together cutting-edge science fiction with Lafferty’s boisterous Catholicism, setting out a space or staking a claim for traditional faith within a genre that often eschews it, and without the moralizing or simplistic allegory that such efforts are prone to. It does so in a style and voice that are so immediately distinct and different from anything else in the field that it made intense fans out of many people whose philosophical preconceptions were diametrically opposed to Lafferty’s own. In all these ways, it serves as an excellent introduction to the work of a writer who, whatever your own cultural and ideological allegiances, will show you a new vantage point on this world and all the new worlds that may yet come.

Andrew Ferguson, a leading Lafferty scholar, is currently at work on a biography of the author. He serves as visiting assistant professor of English and Digital Studies at the University of Maryland.