In 1785, frustrated with the slow pace of reform in his native state, Thomas Jefferson cast his hopes on the next generation of leaders to fulfill his dreams of a revitalized, prosperous Virginia free from the curse of slavery: “It is to them I look, to the rising generation, and not to the one now in power, for these great reformations.” As historian Alan Taylor makes clear in his newest book, Jefferson had a lot to learn.

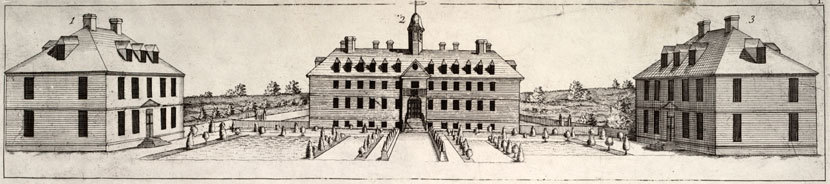

Thomas Jefferson’s Education traces the origins and abortive implementation of Jefferson’s strategy for establishing a democratized system of education in the Old Dominion, one that would cultivate “moral sense” in its future leaders. This complex structure’s capstone was to be a new magnet university that would eclipse the instate rival, Jefferson’s beleaguered alma mater, the College of William and Mary, and offer a Southern counterpoint to the venerable colleges of the North. But Virginia’s small government, low-tax ethos would preclude the full funding of Jefferson’s ambitious plan and ensure that tuition at the flagship university, the only part of the plan to be realized, would be so high that only the sons of the wealthy planter class could attend, prickly, headstrong young men deeply enmeshed in the emerging honor culture of the postwar South. Brought together in bucolic Charlottesville, they proved an unruly lot. In time, many of these students would become key figures in the sectional disputes leading to the Civil War. Designed to remodel Virginia’s slave society, Jefferson’s idealized university—built and operated on slave labor—would in fact help to perpetuate it.

For more than thirty years Alan Taylor has been transforming our understanding of the nation’s founding era, restoring a sense of its extraordinary complexity and endemic conflict. He has twice won the Pulitzer Prize, most recently for The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772–1832, which was also a finalist for the National Book Award. We’re very grateful that he could take time out to answer a few questions about his new book and the state of early American history today.

Library of America: Nearly two hundred years after his death, Jefferson remains a controversial figure, perhaps increasingly so, if the volume of recent scholarship about him is any indication. What led you to want to write this book? What do we learn about Jefferson by focusing on his education, and educational philosophy?

Alan Taylor: I came across Jefferson’s correspondence with his political lieutenant, Joseph Cabell, concerning their efforts to fund a new university and to defund their alma mater, the College of William and Mary. From the 1810s and early 1820s, this political struggle revealed a shift in power within Virginia, as a consequence of the American Revolution. That shift favored the Piedmont region of the state, where Jefferson and Cabell lived, at the expense of the older Tidewater, which included Williamsburg, the site of the older College. Such an exploration fit with my longstanding interest in assessing the impact of the American Revolution on society and politics.

I also thought that exploring Jefferson’s attempts to reform education could speak to our own time of controversy over the structure, goals, and funding for public education, including higher education. We tend to take Jefferson’s ideas out of the context of his own time, to read him as a prophet of a more democratic education in the future. But that interpretation misses the limits that he confronted in a Virginia society committed to many forms of inequality: class, race, and gender. By seeing his own inability to confront those inequalities directly, we can recognize the extent of our own challenges today.

LOA: Thomas Jefferson’s Education is published on the bicentennial of the University of Virginia, where you are the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor of History. Jefferson regarded the University as one of his signature achievements and generations of Wahoos have cultivated a reverential pride in their association with the famous founder. And yet the picture you paint of the school’s origins and early years is a sordid and sobering one. What kind of reception do you anticipate on campus? Any alumni club talks lined up?

Taylor: I greatly admire the university and am in awe of the loyalty and support of the alumni, who have fond memories of their years on the grounds. But I don’t think that such loyalty requires distorting the distant past of the university’s origins. On the contrary, I admire a university that has over the past fifty years done so much to overcome the limits of its origins. By no means do I (or the leadership of the university today) consider that work done. But the determination that I see to improve the university and make it more welcoming to the broadest array of students gives me great hope. And yes, I regularly give talks to alumni groups—where I have always found a warm welcome and a deep desire to know more about the history of the institution.

LOA: You include vivid accounts of the boisterous parties, fights, duels, and even riots that occurred at William and Mary and the University of Virginia in Jefferson’s lifetime—accounts that would make Animal House seem tame. Were you surprised by the scale and frequency of this unrest? Can you talk about your research into these episodes? Had any effort been made to suppress this history?

Taylor: I was taken aback at the depth and extent of violence perpetrated by students—on townspeople, enslaved people, faculty, and one another. This turmoil affected every university in the early republic—but it was most violent and frequent in southern institutions, including the universities of Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina—all of them older than UVA. The evidence comes from newspapers, private correspondence, and especially from the disciplinary records of these universities. It reveals a pervasive culture of honor sustained by the sons of slaveholders who felt that their mastery over others required them to resent any insult, any slight, and any effort to exercise control over them. These episodes are well known to specialists on the histories of particular universities. I hoped to contribute by showing the links between these different universities in the shared culture of elite young men in a slave society.

LOA: Your book comes at a time when many older universities are reckoning with the legacy of slavery in their early history. Do you see it as a contribution to that larger conversation? Do these centuries-old moral compromises bear on the way we think about higher education today?

Taylor: I have greatly benefited from the revelations of other scholars, working with the support of university administrations, seeking a fuller accounting of the origins of their institutions. I hope to contribute by embedding early universities in their broader societies, when and where slavery was the tragic norm, and a norm that distorted every aspect of life and culture. So while the book does attend to abuses at universities, it also explores why the students arrived so poorly prepared, for want of public support for primary education and academies (what we call high schools today). Universities reflect the societies that sustain them—for better and too often for worse. If we want to improve our societies in any way, it may be necessary to reform education—but that will not be sufficient.

LOA: One of the ironies of your book is that Jefferson was more successful in imparting his educational vision to his daughters and granddaughters, who could have no public role in charting Virginia’s future, than to the boys and young men at his university. How did Jefferson understand the role of female education in society?

Taylor: Jefferson is a fascinating, compelling character because he had such a searing intellect but he wanted acceptance within a society that he found so troubling. So he made many compromises with what was then conventional wisdom, including the notions that only elite women warranted anything more than primary education—and that their education should only prepare them to become ornamental wives and instructors for their own children. Virginians did not want to educate women to pursue careers outside of the home. So it is striking that so many young men made so little of their educational opportunities while Jefferson’s grand-daughters made the most of theirs and some of them did achieve careers as teachers, something that their grandfather never anticipated. But they had to do so, in part, because his estate collapsed, leaving them with no inheritance except for the special, loving education that they had received from him.

LOA: There was a dramatic difference between the way the nation marked the centennial of the Civil War in the early 1960s and the sesquicentennial earlier this decade, a measure of how much the country had changed in the intervening decades. Do you anticipate a comparable evolution with respect to the coming 250th anniversary of Independence, as compared to the Bicentennial? How would you assess the state of public understanding of the founding era today? Is there any one misconception about the period you would most like to dispel?

Taylor: I recall experiencing, as a child, the Civil War centennial and, as an adolescent, the bicentennial of the American Revolution. Both were simpler times with celebratory central narratives that enjoyed robust public funding. That funding has dried up for subsequent anniversaries because our narratives have become more contested. Legislators don’t want to invest in remembering Reconstruction if it shines attention on how the KKK destroyed the political rights of millions and killed hundreds. Having written on the American Revolution and discovered the deep and violent divisions among Americans of that generation, I suspect that the 250th will be a much more muted and underfunded affair.

We have such an ingrained cultural reflex to divide people into “good guys” and “bad guys” that it becomes virtually impossible to come up with a more nuanced understanding of the past, filled with the interplay of light and dark in institutions and individuals. We could reach a deeper understanding of our origins if we stopped casting the leaders there as either heroes or villains, but instead placed them within the world that they lived in.

So while we should examine the distorting power of slavery, and the failure of most of the founders to confront it, we should not do so simply to dismiss or demonize them. On the contrary, we should seek a sobering sense of how difficult it is for people in any time to do the right thing when it contradicts powerful economic interests and engrained prejudices. If we dismiss and demonize (or celebrate uncritically) leaders of the past, we gain a false sense of our own superior virtue and risk overlooking what we ought to be doing now—and the difficulties that we face.

Alan Taylor is Thomas Jefferson Chair in American History at the University of Virginia and the recipient of two Pulitzer Prizes and a Bancroft Prize. His many books include American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies, and William Cooper’s Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic. For Library of America he has edited James Fenimore Cooper: Two Novels of the American Revolution.