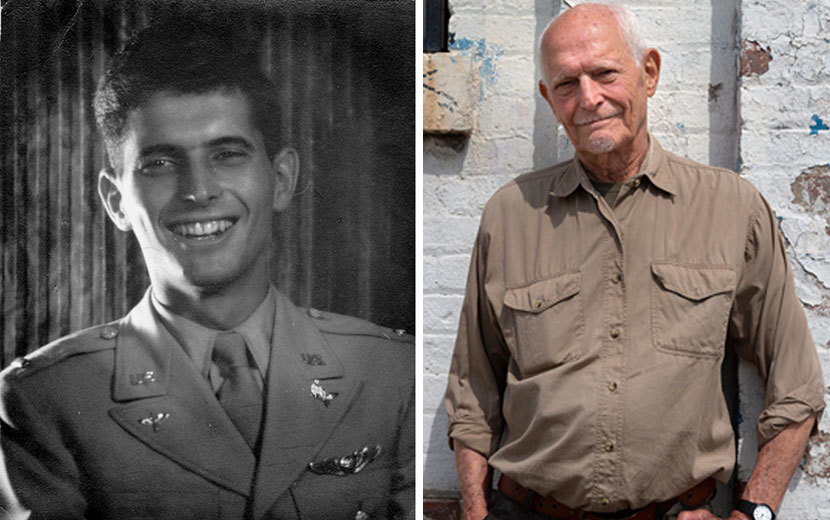

In early 1945, twenty-year-old Long Island native Edward Field was a second lieutenant in the 8th Air Force, serving as a navigator on bombing runs over northern Europe. In a raid on Berlin that February, his B-17 was crippled by flak and crash-landed in the North Sea. All ten crew members made it into the plane’s life rafts, but by the time they were picked up by a British air-sea rescue boat hours later, three of them were no longer alive. One of the dead men effectively gave his life so that Field could live.

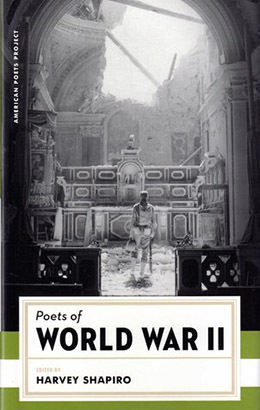

Twenty-two years later, Field turned this experience into a gripping narrative poem, “World War II,” which is collected in the Library of America anthology Poets of World War II. Now, nearly seventy-five years after the events it recounts, the poem is being turned into a short animated film, Minor Accident of War, narrated by the 95-year-old Field himself and produced by his niece, Diane Fredel–Weis.

Minor Accident of War will undoubtedly bring renewed attention to Field’s remarkable career, which began in the late 1940s and has yielded, to date, ten collections of poetry, two works of nonfiction, numerous anthologies, and several novels co-written with his late partner Neil Derrick (1931–2018). A film for which he wrote the narration, To Be Alive!, won an Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject) in 1966. Field has also been recognized as an LGBTQ pioneer: a writer and a veteran who was open about his identity as a gay Jewish man at the height of Cold War America. As he told an interviewer in 2017, “Part of the problem I had publishing my first book was my frankness about being gay, being Jewish—that was not acceptable at the time. I got twenty-five rejections before my first book was published.”

Additionally, the new film underscores what is perhaps the most poignant milestone among Field’s achievements. Of the sixty-two poets included in Poets of World War II, he’s the only one who is still alive.

Via email, we talked with Executive Producer Diane Fredel–Weis about Minor Accident of War.

Library of America: Tell us about the creative genesis of the film. When did you know you wanted to adapt your uncle’s poem, and was it always your intention to make it an animated film?

Diane Fredel–Weis: I visited my uncle Edward in November 2018 and he was struggling with the loss of his partner of almost sixty years, Neil Derrick. I was going through a difficult divorce. I thought it would be a good idea for both of us to work together on a project and was familiar with his poem “World War II.” I suggested to Edward the concept of adapting it into a short film. He loved the idea.

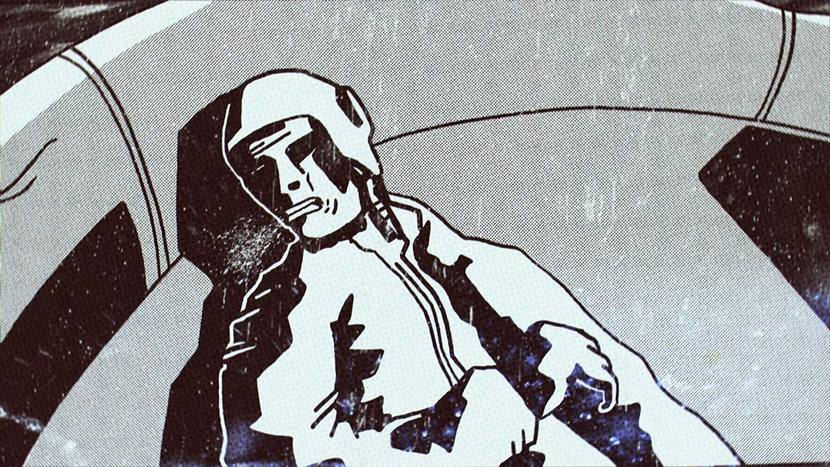

Animation seemed to me to be the best way to tell the story because we could combine a cool, contemporary style with a historical piece. As everyone will see, the animator, Piotr Kabat, did an extraordinary job. I didn’t do a traditional adaptation into a screenplay because I thought it would be powerful to have Edward narrate it. He lived it. He wrote it. He narrates it. Quite a trifecta.

Lastly, the seventy-fifth anniversary of the end of the war is next year, so I wanted to have it done in time for that.

LOA: What are your current exhibition/distribution plans for the film? Will it eventually be available via streaming or other platforms?

Fredel–Weis: We’re submitting to film festivals. We will update our website with screenings, so readers can check ww2shortfilm.com. We also plan on having screenings at history museums as well. Eventually it will be online.

LOA: How did the production come together? From the “Making Of” page on the project website, it looks as if at least part of the creative team is based in Poland, for instance.

Fredel–Weis: Yes. It’s an international labor of love, you could say. The first thing I had to do was find an animator who had good storytelling skills. My co-producer David Finch and I spent weeks looking at videos online, especially on Vimeo. When I saw Piotr Kabat’s page and his videos, it was like, Bam!—exactly the style and vibe I envisioned.

I saw he lived in Poland but that didn’t deter me. I emailed him and he loved the poem and the project and came onboard. Important to note, he is an animation filmmaker. He has great instincts as an artist and animator. Through him, we got the interest of the brilliant sound designer Michal Fojcik in Krakow. Since this was my first fully animated film as a producer, I reached out to a former colleague at Disney, Alex Kupershmidt, who is now a senior-level animator with the studio. He came on board as a consultant. For music, I reached out to a talented musician friend in New York, Alex Gimeno. Edward’s two great–nephews, Stephen Cyr and Gabriel Weis, are also part of the production. While we are a very small team, everyone is incredibly dedicated and passionate about making the film the best it can be and honoring Edward.

Because of the logistics, we worked together mostly through Zoom video sessions, emails, and phone calls. Edward provided incredible details from almost seventy-five years ago to help us make the film as authentic as possible. On the website, you can see others who have supported the project. I am just so grateful for how everyone and everything came together, and excited about getting the film out there in front of audiences.

LOA: “World War II” appeared in 1967, twenty-two years after the events described. What has Edward shared with you about the poem’s gestation? Did he need the distance of intervening decades in order to be able to capture the experience in words?

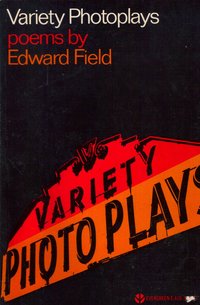

Fredel–Weis: Edward has said he needed the time between the events of February 3, 1945, the day of the fateful mission, and 1965 to mature as a poet and learn how to write a narrative poem. The book this poem appeared in, Variety Photoplays, is focused on old movie plots, so it’s appropriate that “World War II” should also become a movie.

LOA: Did Edward ever hear from any of his fellow crew members after he published “World War II?” What about family members of the men who died on the return?

Fredel–Weis: As far as Edward knows, no members of the crew are still alive, and he didn’t keep in touch with their family members either. The daughter of a pilot from the war, Cindy Farrar Bryan, tracked down the family of the ball turret gunner, Jack Coleman Cook, who gave his life for my uncle on that mission. She worked to get him recognized. She and Edward both were in D.C. last year when Congressman Bruce Westerman of Arkansas spoke on the floor and honored Cook. Cindy has been a research consultant as well on this film.

LOA: Edward Field’s life and long career have been distinguished by several kinds of heroism. There’s the kind we read about in “World War II,” obviously, but he also contended with anti-Semitism as a child and adult and with homophobic prejudice in the early years of his writing career. Is it your hope that your film might help educate contemporary LGBTQ audiences about his achievements?

Fredel–Weis: Edward does not consider himself a hero but he is in my opinion and others’. Edward and his siblings, including my mom, endured horrible anti-Semitism growing up in Lynbrook, New York, in the 1920s and ’30s. Edward says he was treated worse for being Jewish than being gay. My other uncle, Richard Field, who is 91, says a teacher would punch him in the face just because he was Jewish. When Edward joined the military, he says he was accepted like he had never been. He lived a gay life in the Air Force in the 1940s. He has told me no one ever gave him a difficult time and has often said it was one of the best experiences of his life.

Edward is sort of already a rock star. He has lots of fans, me included. I am hoping that people see the film, learn more about Edward’s service, and think about being more tolerant and understanding about LGBTQ people wanting to serve our country in the armed forces. (I’d also like to say thanks to Library of America for raising awareness of Edward and our film.)