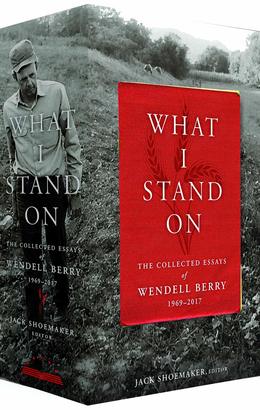

Recently released by Library of America, What I Stand On: The Collected Essays of Wendell Berry 1969-2017 is a definitive two-volume edition of the writer, farmer, and activist who has made his home in rural Kentucky for more than fifty years. What I Stand On presents such landmark Berry texts as The Unsettling of America (1977) and Life Is a Miracle (2000) in their entirety, along with generous selections from more than a dozen other books. More than any previous anthology, it reveals the full evolution of his thoughts and concerns as a social critic and ecological philosopher.

Assessing the set in a rich, laudatory review for The Nation published just this week, Jedediah Britton–Purdy writes that “Seeing [Berry’s] arc in one place highlights both his complexity and his consistency” and that “the core of his work—both writing and activism—has always been after . . . a reckoning with the wrongs of history and identity.”

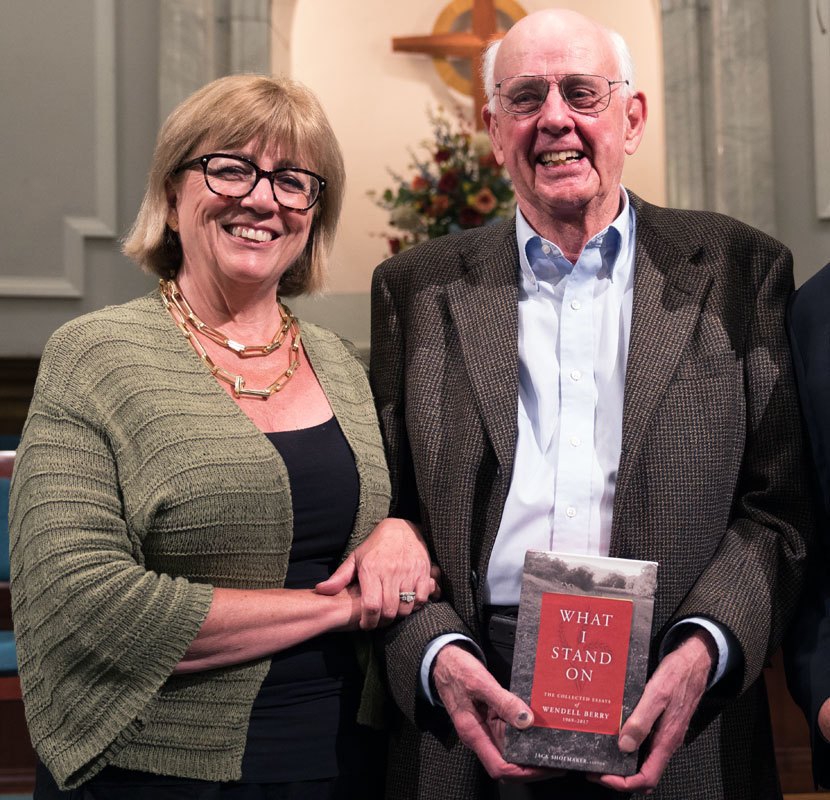

For another estimation of What I Stand On we turned to someone with a special perspective on Berry’s work: Mary Berry, who is both Wendell Berry’s daughter and Executive Director of the Berry Center in New Castle, Kentucky. Dedicated to extending the reach of Wendell Berry’s writings and putting his values into practice, the Berry Center serves an advocate for small and middle-sized farms, land conservation, and “healthy regional communities,” to use the phrase on its website.

Library of America: In practical terms, how do you see the work you do at the Berry Center extending or perpetuating your father’s legacy?

Mary Berry: I started the Berry Center in 2011 to continue the work of my family for small farmers and land conserving communities, and to improve the culture of agriculture. My father says that his father, John Marshall Berry, did the important work and he and his brother, John Marshall Berry, Jr., just took it up. We have now taken it up at the Center, advocating for ways to put a stabilizing economy under good farming and to foster a culture that will support it.

We started with an archive of my family’s papers, papers that tell the story of how the agrarian mind works when put into service of a particular place. My grandfather, John Marshall Berry, was a lawyer, farmer, and principal author of the only farm program in the history of our country (the Burley Tobacco Growers Co-Operative Association) that served the people it was supposed to serve—the small family farmer. His papers highlight the program and a way of life that he honored. We have to change the way we judge and understand the history of agriculture in this country. These papers give us a way to do that.

LOA: Do you have a favorite essay or group of essays in What I Stand On? And, for readers who might be daunted about approaching a 1,700-page collection, what’s a good place to start with Wendell Berry’s nonfiction?

Berry: I don’t think that readers should be daunted. After all, this is broken up into essays. The reader should start wherever they want to. I love the essay “A Native Hill” because it is about the place where I grew up and where my parents live now. And I love to think of my father as a young man walking the farm that would be his life’s work.

LOA: Wendell Berry has said that reform of the agricultural system is going to have to come from consumers, and the Berry Center is working to help farmers farm well. How do we get these two paths to converge?

Berry: Food is a cultural product. The growing interest in and demand for local farm products in urban places has come up against a declining culture in rural places. There has been precious little acknowledgment of this because I don’t think most people recognize it as a problem. But the problem is unsettling America. Rural places have had their raw materials stolen at the lowest possible price throughout our recent history. The bill is coming due. So, we need an urban constituency to advocate for the land and the people of the land beyond just buying local. We have a lot of rebuilding to do to get that done. But it is the most hopeful work I can think of.

LOA: Your father once stated, in a 2008 interview with The Sun, that “Industrial agriculture is an urban invention, and if agriculture is going to be reinvented, it’s going to have to be reinvented by urban people.” What do you think he meant by that? Does the idea jibe with your own experience as a farmer, and as an advocate for small farmers?

Berry: My father starts that statement with this, “When the producers—the farmers—are going broke, it’s wrong to expect them to reform the system. In fact, there are too few actual farmers left to reform anything.” He said that in 2008 and the problem has only worsened. In fact, it was the realization that forty or so years of a local food movement had not changed the culture of agriculture in this country that got me started on the idea of the Berry Center. Are we or are we not going to take care of our land and our people? The answer to those questions has so far been mostly no. We need our urban neighbors to know more about the farming and farmers close to them and become, as I said before, advocates for an economy and culture that will support sustainable small farming.

LOA: Wendell Berry has had an extraordinarily productive literary career that now stretches across six decades. Do you remember when you first started to engage with your father’s writing, and what effect it had on you? (Was it fiction, nonfiction, poetry—?)

Berry: Other than what my father read aloud to my brother and me, or maybe we were just listening when he read his work to my mother and to his friends—I had read nothing of his when I went to college. Some of my friends were reading The Memory of Old Jack (1974) in their freshman English class. I, responding to peer pressure I suppose, read it too. I thought it the most beautiful book I’d ever read. It was a story of my place, of my people. But it also terrified me. The book tells the story of Old Jack’s relationship with his daughter Clara. It is the story of estrangement. I wrote to my father and asked, “Am I Clara?” (I had been a pretty dissatisfied teenager!) He wrote me back and said that indeed I was not Clara. That Clara and her father had become strangers to each other. This, he said, would not—could not—happen to us. And it has not happened to us.

In my work at the Berry Center, whether I am writing something or in my thinking, I sometimes get stuck, and don’t know the next step. When that happens I depend on my father’s work to help me. I just open one of his books, be it poetry, essays, or fiction, and start reading and my way becomes clearer.

LOA: What it is like to come from a long line of farmers in today’s political climate? Do you see signs of the wider culture’s polarization in your community?

Berry: The urban–rural divide in this country is possibly the most ruinous of all the false separations in our culture and economy. I’ve already spoken of that but it bears repeating. I grew up in a fairly stable farming community. With the loss of a sustainable small farm economy that community is falling apart. Differences that didn’t matter much when we had a good farm economy now matter absolutely. The community I grew up in tolerated political and social differences pretty well. Now they matter.

I come from a long line of people who have a passion for farming on a particular place on earth. We are working at the Berry Center toward a culture and an economy that will once again allow people, especially young people, to nurture that same passion for the land. This is what we need in order to stop destroying the source of everything that’s necessary for our survival. It’s what people are for.