Our “Influences” series of guest blog posts by contemporary American writers returns with a column by poet Matthew Zapruder, whose fifth book of verse, Father’s Day, has just been published by Copper Canyon Press.

“One of our funniest, most technically virtuous poets enters an intimate, new stage of work in his moving fifth collection,” LitHub says of Father’s Day, adding that the book is full of “un-celebratory anthems and disquieting odes.” In his new poems, Zapruder grapples with questions of ethics and morality in the unsettled (and unsettling) early twenty-first century; the nature of contemporary parenting, Supreme Court justices, and poetry critics are just some of the subjects he addresses with the linguistic precision and honest good humor for which his work is known.

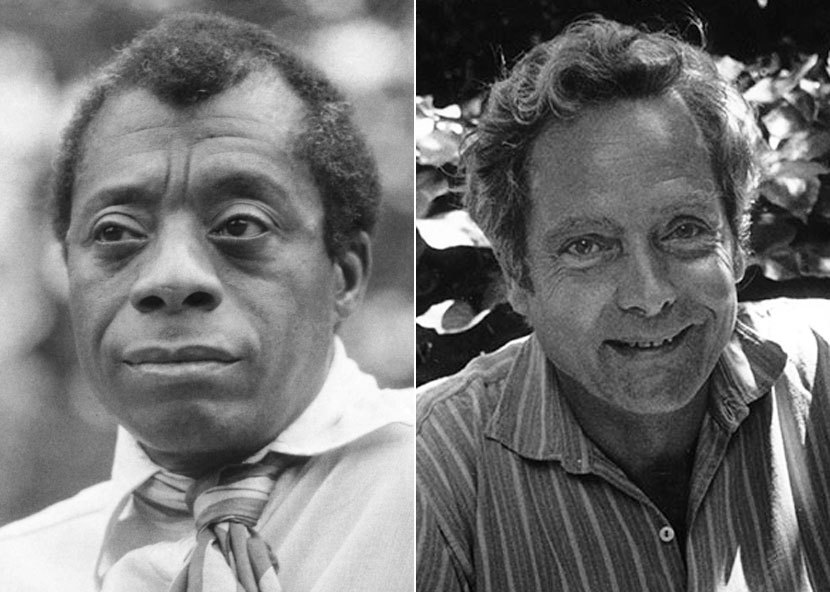

Below, Zapruder reflects on two American writers whose work inspired him in the course of writing Father’s Day.

I am embarrassed to say that before I taught Notes of a Native Son in a graduate seminar a few years ago, I had never read an entire book by James Baldwin. To be immersed in the clarity of his thinking about race and many other matters crystalized so much of my vague thinking. Many moments in these essays had a profound impact, but two in particular served as constant guides.

Writing about Richard Wright’s Native Son in “Many Thousands Gone,” Baldwin diagnoses our ability to invert what should be a catastrophic critique into self-praise:

Americans, unhappily, have the most remarkable ability to alchemize all bitter truths into an innocuous but piquant confection and to transform their moral contradictions, or public discussion of such contradictions, into a proud decoration, such as are given for heroism on the field of battle.

That is basically a description of a good amount of our social discourse. This sentence served as a reminder to me, when writing about race and privilege and difference of all kinds, not to turn my own poems into those exact sorts of little medals to be pinned on my own chest.

And here is the final sentence of “Everybody’s Protest Novel” — “The failure of the protest novel lies in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power, in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is real and cannot be transcended.” We live in a time when those we agree with and those we oppose seem equally likely to treat a person’s “categorization” as the only thing that is truly real about them, and it was bracing to see that one of our greatest and most courageous writers opposed this type of thinking.

Retyping Baldwin’s lines, I am also once again struck by his attention to language, and his ability to activate it. I adore and revere the perfect accuracy of “bitter truths,” and the wit in the selection of “alchemize,” “innocuous,” “piquant,” and “confection.” I also love how he doesn’t shy away from huge words so often emptily deployed, like “beauty,” “dread” and “power,” how he is able to bring nobility and meaning back to them. I want to do that in my poems.

During the writing of Father’s Day, I turned 50, coterminously with W. S. Merwin’s classic volume of poetry The Lice. One of my guiding poets has always been Merwin, aka the Wizard. I was asked by Copper Canyon Press to write a preface to a beautiful reissue of The Lice, which caused me to begin to reread several of his books of poems and prose, to see what has always influenced me and also new things I hadn’t noticed.

Right toward the end of the writing of Father’s Day, I had a chance to go see him on Maui, in his house in Haiku, which he built with his own hands in the middle of what he made into a palm forest, where rare species of trees are preserved. It’s a singular place, and to sit with him for a little while toward the end of his life (he died on March 15th, 2019) on the lanai overlooking the trees and the nearby Pacific was an intimate privilege. All through the writing of this book, his drifty, ghosty poems, which are somehow both abstract and specific, impersonal and intimate, plain and musical, once again kept me lonely company.

Matthew Zapruder is the author of four previous collections of poetry, most recently Sun Bear (Copper Canyon, 2014) and Come On All You Ghosts (Copper Canyon, 2010), as well as a book of prose, Why Poetry (Ecco Press, 2017). He has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, a William Carlos Williams Award, and a May Sarton Award from the Academy of American Arts and Sciences. Zapruder co-founded Verse Press in 2000 and is now editor at large at Wave Books. In 2016–17 he held the annually rotating position of Editor of the Poetry Column for the New York Times Magazine. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he is an Associate Professor at Saint Mary’s College of California.