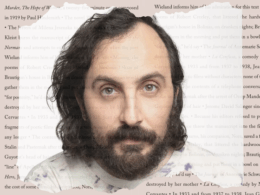

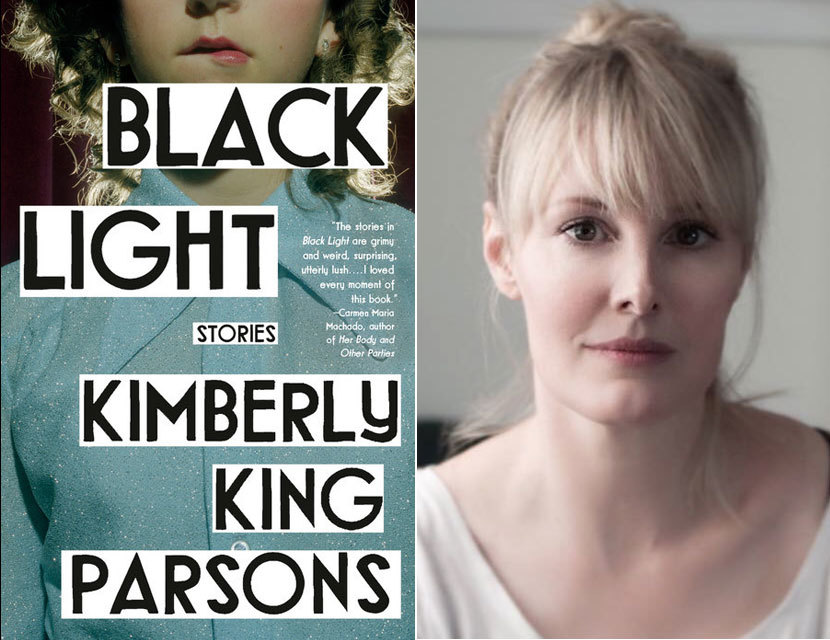

Our series of guest blog posts by contemporary American writers continues today with a contribution from Kimberly King Parsons, whose debut collection of short fiction, Black Light, lands this week from Vintage Books.

Black Light has already been named a “Staff Pick” by the Paris Review Daily, whose reviewer enthused, “Parsons is both unflinching and eloquent in her portrayals of people as they burn and rage,” and Carmen Maria Machado (whose own debut collection we featured in this space nearly two years ago) says she “loved every moment” of the book’s “grimy and weird, surprising, utterly lush” stories.

In the column below, Parsons acknowledges her own personal pantheon—the writers who all helped inspire the breakthroughs that led to Black Light.

Amy Hempel, Reasons to Live. I read this collection when I was a teenager, and it’s fair to say my life was split into everything before and everything that came after. Hempel says the ending of a story should punch you in the heart, and when I first finished “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried,” I was wrecked, but more than that, I was curious. How did she manage to destroy me in such a tight space? This book put me on a lifelong path of short story reading and writing, and it was my first lesson in urgency, compression, and an accessible, plainly affecting voice. I carry Hempel with me everywhere (I mean this quite literally—I have a line from Reasons to Live tattooed on my forearm).

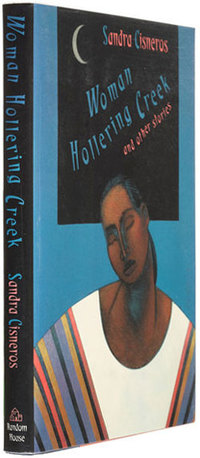

Sandra Cisneros, Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories. Told in a poet’s eloquent prose, these stories radiate heat, rendering the particular sights, smells, and tastes of San Antonio—a place very different from my own Texas experience—vivid and indelible. Cisneros gets place on the page without lengthy descriptions—a few quick, precise details and she knits a whole world. Plus, nobody writes the child perspective with as much believability and tenderness; Cisneros never leans on precocity, but instead lets her kid narrators be impulsive, stupid, wicked, and, somehow, achingly empathetic as they attempt to make sense of this beautiful, frequently unfair life.

Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son. Johnson writes headlong into the deepest, darkest recesses and manages to come out radiant, funny, and full of hope. This is a book I reread every year, and each time I get the same sick, electric feeling. Sick not because of the despicable (yet utterly endearing) narrator’s horrific struggles with addiction, but because Jesus’ Son is an excruciatingly perfect story collection—Johnson has done it, the rest of us might as well give up. But then there’s the electricity. The language hums and pulses, so celestial and alive it makes the sticky, frustrating pursuit of putting the right words in the right order feel like a holy thing, worth trying and failing at for your entire life.

Joy Williams, Taking Care. Full of failing marriages and fractured families, the stories in this collection plug you directly into Williams’s tremendous intellect and gloomy, whirring imagination. Her sentences are crystalline marvels, by turns playful and menacing. The stories tip toward the bleak and bitter, but no other book makes me laugh quite so hard. In exhilarating, unexpected prose, Williams posits glee in the face of the ridiculous, random atrocities, big and small, that befall her characters.

Barry Hannah, Airships. This was another collection that seeped into my ready, adolescent brain and changed me for the better. Hannah’s Southern gothic motifs are classically compelling—blindness, incest, the violence of war—and his impeccable craft glides under familiar, sometimes crude, voices. These stories are funny, right up until the moment they shred your heart. One of my undergraduate creative writing professors made us go through the story “Water Liars” line by line to see how each sentence “seeded” the next. This was the first time it had ever occurred to me that prose could be held up and examined, that patterns were visible, could be predicted, and, amazingly, could be replicated in our own work. My copy is marked all to hell—a treasured love letter from my younger self.

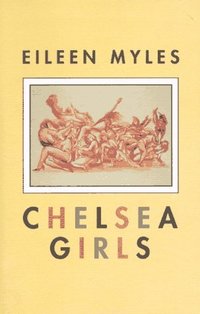

Eileen Myles, Chelsea Girls. This is the only book here that isn’t a collection, though I read it as if it were—each audacious story spit out by a charismatic, iconic character: a poet called Eileen Myles. Full of swagger and immediacy, the prose is rambling and sloppy by design (“With me sloppy has always been good, meant sexy,” Myles says). Effortlessly cool and funny, with wry, brittle observations that cut to the quick, Chelsea Girls is a case study in myth-making—a book about identity and art and the young artist, told in a voice I’d follow anywhere.

Kimberly King Parsons is the recipient of fellowships from the Sustainable Arts Foundation and Columbia University, and her fiction has been published in The Paris Review, Best Small Fictions, New South, Black Warrior Review, No Tokens, and Kenyon Review, among other outlets. Born in Lubbock, Texas, Parsons now lives with her partner and children in Portland, Oregon, where she is completing a novel about Texas, motherhood, and LSD.