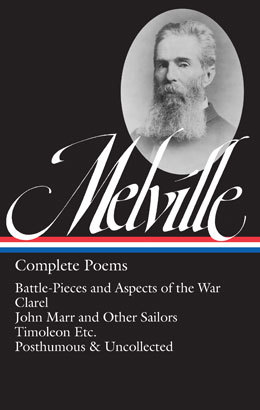

Herman Melville was born 200 years ago today, on August 1st, 1819. Library of America marks the Melville bicentennial with the publication of Herman Melville: Complete Poems, the fourth and final volume in its Melville edition, which began back in 1982 with the very first LOA title, Herman Melville: Typee, Omoo, Mardi.

Complete Poems collects, for the first time in one volume, all four books of poetry Melville published in his lifetime—Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866); Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1876); and his two late, privately published collections, John Marr and Other Sailors (1888) and Timoleon Etc (1891)—along with uncollected poems and the poems from two projected volumes left that he left unfinished at the time of his death.

Melville’s verse combines the precise physical detail and rich metaphysical speculation of Moby-Dick and his other prose classics with an unorthodox style and compressed power uniquely his own. By presenting this body of work in its entirety, Complete Poems reveals the full measure of a major nineteenth-century poet who deserves to be ranked alongside Dickinson and Whitman.

The fruit of decades of textual scholarship, the new book presents all of Melville’s verse in the authoritative texts established by the multi-volume Northwestern-Newberry Edition of The Writings of Herman Melville, and is edited by Hershel Parker, the General Editor for the final two volumes of the Northwestern-Newberry Edition.

Parker is the H. Fletcher Brown Professor Emeritus at the University of Delaware and the author of several books, including Melville: The Making of the Poet, Melville Biography: An Inside Narrative, and Herman Melville: A Biography, a finalist in 1997 for the Pulitzer Prize. Via email, he discussed the herculean labors that went into establishing authoritative editions of Melville’s writing, and his own lifelong involvement with the poetry, in particular the epic Clarel, the long-gestating fruit of a trip Melville took to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Holy Land in the mid–1850s.

Library of America: It’s extraordinary to reflect on the fact that the first one-volume edition of Melville’s poetry is making its appearance only in 2019, in the bicentenary of Melville’s birth. Can you give a brief account of the Northwestern-Newbery edition, and all the work that needed to happen to make this publication by Library of America possible?

Hershel Parker: In the early summer of 1965, the Office of Education in the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare gave Harrison Hayford, Thomas Tanselle, and me a mandate to produce the multi-volume edition The Writings of Herman Melville, headquartered at Northwestern University and the Newberry Library. Hayford was General Editor, Tanselle was the Bibliographical Editor, and I was Associate General Editor. The goal was to produce critical texts of all of Melville’s writings. 1965. Is that a long time ago? Yes, even to me. The final volume of the edition—which presented new texts of the uncompleted prose and poetry, including the extraordinary Weeds and Wildings and Parthenope—was published in 2017. Library of America’s Complete Poems had to wait for its appearance.

LOA: As you reflect on the completion of the Northwestern-Newberry edition of The Writings of Herman Melville, what were the greatest challenges you and the other editors faced?

Parker: It’s a good question—one I talked about in a new retrospective piece in Leviathan, the journal dedicated to Melville scholarship that is published under the aegis of the Melville Society. I’m repeating what I said there, but if you had asked me in the late 1960s, I would have said the hardest work on the NN volumes was seeing that collations were made accurately and that the requisite textual lists were carefully produced and the textual decisions justified. Or I might have said the hardest part was getting adequate Historical Notes. Decades later, I might have said that the hardest part for the last few volumes was Alma MacDougall’s role successively as editorial coordinator, executive editor, then simply editor.

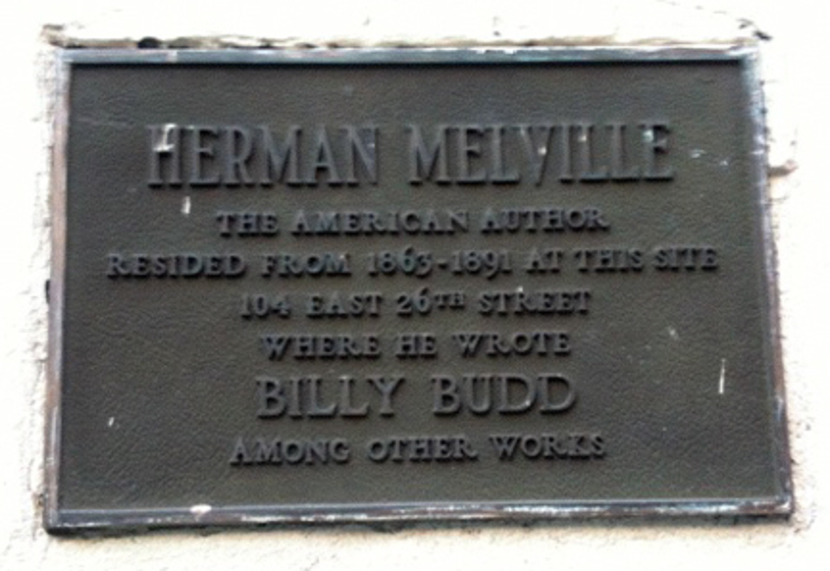

Now I would say that the hardest work was in deciphering Melville’s hand in his journals, letters, and uncompleted manuscripts—work undertaken by several of us associated with the thirteen-volume edition. Howard Horsford fought his way through the 1849 and 1856–1857 journals (he had edited the second of these in the 1950s), with the assistance of Lynn Horth. The Hayford–Sealts edition of Billy Budd (1962) had featured Hayford’s transcription; for the NN volume, Tanselle and MacDougall revised it on the basis of further study of the manuscript. Merton M. Sealts in working with Melville’s unpublished papers had thrown up his hands at one lot of apparently illegible prose leaves, but Robert Sandberg in the late 1980s found that they consisted of a previously unidentified piece, “House of the Tragic Poet.” Further revised, his transcription is in the Billy Budd volume, and the skills he had honed in the 1980s were enhanced in the 2010s as he transcribed the uncompleted poetry, and then later weighed his new transcriptions against those Hayford left in elaborate notebooks. Hayford, Horsford, and Sandberg displayed an all but superhuman capacity to read Melville manuscripts. They are in a heroic class by themselves.

For NN, my contribution to transcribing was the new trove of Melville family documents, a portion of the archive of Melville’s sister Augusta acquired by the New York Public Library in 1983. Librarians quickly pointed out the most glamorous material, anything relating to Hawthorne and letters from Melville himself, and those were seized upon, but no one undertook a systematic transcription of the documents that involved dating them, when necessary, and identifying people unknown to Melville scholars. Thanks to the letters and her correspondence log I was able to create a day-by-day (sometimes hour-by-hour) account of Melville’s meeting with Hawthorne and his subsequent writing his essay on Mosses from an Old Manse. That and much else from the Augusta Papers went into the Historical Note to the NN Moby-Dick. My transcription of previously unpublished documents went into Historical Notes not only for Moby-Dick but (very largely) the editorial sections of Correspondence. My transcriptions for The Melville Log: A Documentary Life of Herman Melville, 1819–1891 went into a Historical Supplement for Clarel, then into the Historical Notes for Published Poems and the Billy Budd volume.

LOA: Did the poetry present special difficulties? What about the two unfinished books, Weeds and Wildings and Parthenope?

Parker: The uncollected Weeds and Wildings was a mammoth job for Robert C. Ryan, at first, then for Robert Sandberg, who grappled with that book and Parthenope. Did the poetry present special difficulties? Yes, partly because many of the poems were in manuscript, calling for heroic transcriptions from Robert Sandberg as well as meticulous descriptions. Mainly, the poetry presents special difficulties because we can’t be sure of the contents of his Poems—which predates Battle-Pieces. At least two publishers rejected the manuscript in 1860. His brother Allan could have paid a few hundred dollars to have the book published after it was rejected. Or Evert Duyckinck could have paid for it, knowing what it meant to Melville and his wife. It breaks my heart that they did not do that much for Melville. Anyway, the fact is Poems wasn’t published, and the manuscript isn’t known to survive. What did his lost volume of poems contain? It can only be inferred that individual poems survived and were later reworked. It very likely included “At the Hostelry,” “An Afternoon in Naples” (without prose insertions), and “After the Pleasure Party.”

If published in 1860, Melville’s poetry might not have been praised, but it would have been readily placed by readers. Melville would have been understood as a poet of the Risorgimento like the Brownings and he could have been seen as a modern explorer of women’s place and women’s rights like Tennyson in “The Princess.” As it is, we are stuck with some late 1850s poems with interpolated prose pieces belatedly assigned to characters he invented for prose sketches toward the end of the 1870s. We do our best, but we can never recreate Poems, never fully grasp the biggest part of what Melville was doing for three years or so. Our sense of the trajectory of Melville’s working life is blurred.

I had better say something flat out. In 1857–1860 Melville was not obsessed with slavery the way Thoreau and many others were. Melville was not worrying day and night in the late 1850s about Abolitionists and the hapless President Buchanan. In The Confidence-Man, finished in 1856, Melville had portrayed his new America—where politics, society, religion, philosophy, and personal relationships were all infused with the blithe fatuity of a new country that had sold itself on the notion of a divinely manifest destiny. After his return from his Mediterranean trip in 1857 Melville had taken refuge in history, art, and poetry. This should be understandable to people in 2019 who are frightened for the future of the country (never mind the world) and are trying with all their strength to live in political denial.

LOA: How many times have you read Clarel? Tell our readers why you like it.

Parker: I got my copy of Clarel on February 17, 1962, but I may not have started it until I was in New York City in June living in a room about three times the size of the sleeping box in Wuthering Heights. I got through the first book, “Jerusalem,” and despite Walter E. Bezanson’s helpful annotations I bogged down and had to go back to the opening, and that time I made it through. Since then I have read it perhaps ten times all through and taught it in graduate classes six or seven times. I always asked the students to focus on limited aspects such as Clarel’s shifting attitude toward Vine or Rolfe’s conversations with men he saw as his peers or Melville’s dismay at what had happened to the promise of America in the century since 1776. I never taught the poem canto by canto—that would have taken weeks. The students liked the poem more than you might think and appreciated that it showed some characters shifting opinions, developing. Of course, when you write a poem section by section over several years, you do some shifting yourself along with your characters.

I always marvel at Melville’s ruthless analysis of Clarel’s changing awareness of his sexual nature, which involves Melville’s own wry, amused understanding of his own early passionate response to Hawthorne. I admire Melville’s restrained, respectful analysis of Vine’s lasting appeal, glamour remaining after intellectual powers have diminished. But what I most love is the talk in the poem. The diplomat Maunsell Fields listened raptly for hours as Melville and Oliver Wendell Holmes discussed East India religions and mythologies “with the most amazing skill and brilliancy on both sides.” He declared, “I never chanced to hear better talking in my life.” One of the Williamstown students visiting Melville in 1859, having been lectured to far too long on Plato and Aristotle, nevertheless exclaimed, “what a talk it was!” You can overhear great talk throughout Clarel, even before the journey is quite underway. Now when I read Clarel I begin to feel edgy, vaguely dodgy and sore, as I move into Part Four. That’s when I realize that I am coming to the end and pretty soon there won’t be any more. Whatever Vine and Clarel had to say, whatever Rolfe and Mortmain, or Rolfe and Ungar, had to say, that’s going to be all there is. Reading Clarel, you may echo Maunsell Fields. Whoever you are, you may never chance to hear better talking in your life.

LOA: Can you say something about Melville’s own expectations for Clarel, a poem considerably longer than Milton’s Paradise Lost?

Parker: A writer who works over the proofs of a great book always gets excited. Surely others will realize what a triumph it is! No matter how many times he had been disappointed, he knew he had written a great poem and simply could not imagine it would not be recognized by at least a few readers as great. But Melville was realistic enough in his note to “dismiss the book—content beforehand with whatever future awaits it.” Nobody could have been content three years later when Putnam’s made him agree to dispose of the remaining 224 copies out of some 330 or so printed, paid for by Melville from a legacy for that purpose from his uncle, Peter Gansevoort. He did not even stash a dozen or so to hand out to people who might some day express interest in the volume.

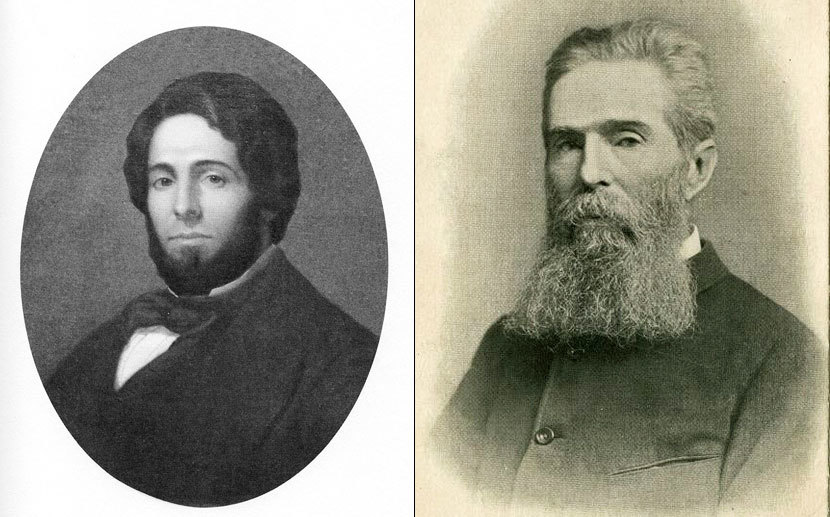

LOA: Most of our readers have some sense of the trajectory of Melville’s career: after several setbacks and disappointments Melville abandoned prose for poetry. Can you fill out or correct that picture? What motivated the change? And what ultimately do you think Melville was able to achieve as a poet?

Parker: We have not yet come to terms with the evidence. Early in 1852 the Harpers’ giving him roughly twenty cents on the dollar for Pierre (in its shorter form) rather than the usual fifty cents all but doomed his career, and the Harpers damaged it further a few months later when they bankrolled a New York Times campaign against any international copyright law (after 1851 Melville would never again receive money from England). He tried to keep going with short stories and The Confidence-Man, but he had to give up in 1857, when he returned from his trip to the Holy Land. I don’t agree with Nina Baym when she speaks of Melville’s “quarrel with fiction.” He had no quarrel with fiction at all. He had a bitter quarrel with the marketplace for fiction.

Starting in 1857, Melville made himself one of the three great American poets of the 1800s. When I read any hundred poems by Emily Dickinson, I know she is the greatest poet of the century. When I read “Song of Myself,” I know Walt Whitman is the greatest poet of the century. But when I look beyond my computer monitor and see framed there “Prelusive” from Clarel beside a Piranesi print, I know that Herman Melville is the greatest poet of the century.

LOA: You have an affinity for the poem “The New Ancient of Days.” Is that your favorite Melville poem? One of your favorites? Can you tell our readers why?

Parker: The poem became one of my favorites when I wrote the notes for the Library of America edition. Now I delight in it as Melville himself did in creating a raucous, jokey poem on great issues of his time, Science and Religion. Melville did not get enough chances to be funny in his last decades.

LOA: Is your work on Melville complete?

Parker: Who knows? In a few weeks I will be giving almost all my Melville books and research folders to the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Melville’s short poem “Suggested by Ruins” concludes:

What solace?—Old in inexhaustion,

Interred alive from storms of fortune,

The quarries be!