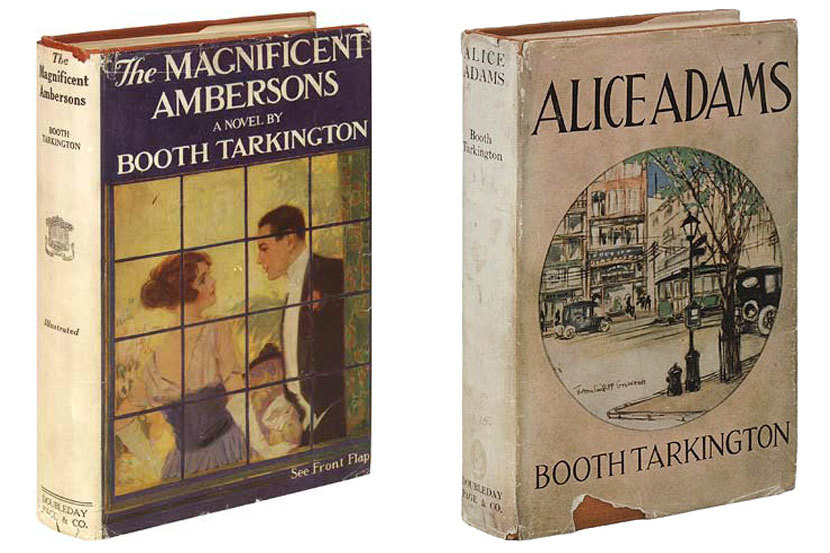

Monday, July 29, marks the 150th birthday of Booth Tarkington (1869–1946), who enters the Library of America series this summer with a volume presenting his two Pulitzer Prize–winning novels The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) and Alice Adams (1921), along with his 1905 short story collection In the Arena: Stories of Political Life, which gave President Theodore Roosevelt one of his signature phrases.

Set in the American Midwest during the throes of irreversible change at the turn of the nineteenth century, these works display a keen realism and astute sense of psychology that fully deserve to be rediscovered; as Jeffrey Frank recently wrote in his Wall Street Journal review, “One can see why readers devoured them, and other Tarkington novels. His satirical asides are perfectly modern.”

Thomas Mallon, the book’s editor, is the author of ten novels, including the recent Landfall, Watergate, Finale, and Fellow Travelers, which was turned into a well-received opera in 2016. A regular contributor to The New Yorker and The New York Times Book Review, he previously edited Library of America’s two-volume edition of Mary McCarthy’s fiction in 2017.

Library of America: Booth Tarkington won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction twice, for The Magnificent Ambersons in 1919 and Alice Adams in 1922. (Among his fellow novelists, only William Faulkner and John Updike have matched that feat.) Yet a hundred years later both books are mostly known through the classic films they inspired. What is the case for reading Tarkington today?

Thomas Mallon: There’s a large harvest of sociological and historical knowledge to be had from reading his vast oeuvre, but the wisest thing to do is to read it sparingly, concentrating on his peak achievements, in which social circumstance is nicely joined to individual psychology. Library of America is good at making judgments, at separating the best from the merely good or—as is the case with Tarkington—the wheat from the chaff. That’s what this new volume tries to do.

LOA: Tarkington’s disdain for industrialization and in particular for the automobile might seem to make him a prophet without honor in his native country. Is this theme in his writing—especially prominent in The Magnificent Ambersons—overdue for reexamination?

Mallon: Yes. Even contemporary environmentalists tend to view the Midwest’s industrial heyday—its pre–Rust Belt, full-lunchbox era—as a kind of social triumph, however unaware people may have been of the ecological price they’d be paying for it. Tarkington saw the humming assembly lines and puffing smokestacks as a bad thing even while they were pumping out prosperity. He thought industrialization was doing bad things to human nature as well as to the landscape. It’s a perspective worth entertaining.

LOA: The famously left-field ending of The Magnificent Ambersons introduces an element of the otherworldly into what is otherwise a work of fairly sober realism. How can we reconcile the ending with Tarkington’s intentions in the rest of the book—and do you think readers today might be less disconcerted by the ending?

Mallon: I think twenty-first-century readers will still have trouble with it. About fifteen years ago, in an essay on Tarkington, I noted how he “once decried unhappy endings as the means by which authors ‘cheaply’ earn a reputation for emotional power—a rationalization, actually, of his own kind of customer relations. His mentor [William Dean Howells] had said that Americans wanted tragedy with a happy ending, and in book after book Tarkington tended to take this witticism for a prescription.”

LOA: On the other hand, no one will find anything compromised or sentimental about any part of Alice Adams, the author’s most tough-minded work. Do we have any clue as to how or why Tarkington managed to transcend “the fatal eagerness to please,” as you have called it, in this remarkable novel?

Mallon: Alice Adams is a splendid, neglected work, the author’s masterpiece, an unsparing study of a little human catastrophe that’s jointly perpetrated by nature and nurture. Tarkington never goes soft in this novel. Outwriting himself, he sees things through to their bitter, true conclusion. The failure of nerve, the happy ending, came this time not from the author, but from the makers of the movie adaptation, which starred Katharine Hepburn. If I may once more quote that essay of mine: “Hollywood took Alice Adams—a great and by now largely forgotten book—and turned it into a Booth Tarkington novel.”

LOA: Tarkington’s one term in the Indiana state legislature inspired the powerful vignettes gathered in the 1905 collection In the Arena: Stories of Political Life, also included in this volume. Has the gulf between literary culture and politics only widened since Tarkington’s day, or could things be shifting in the other direction? Might his exhortations, in the opening of In the Arena, for ordinary citizens to get more involved in government reach receptive ears in 2019 and 2020?

Mallon: I’ve spent much of my career writing novels about politics, and I wish I could give you a more optimistic answer. But the sort of civic engagement that Tarkington recommended—one that prized gradualism, compromise, and the rule of law—is scorned these days in favor of populist bluster on the right and crude moral certainties on the left. A novelist’s imagination is by definition empathetic, trying as it does to make a reader imagine something from an alien or opposing point of view. I’m not sure that’s something people want at this long, bad moment in American culture. They prefer being in a fight to the death.