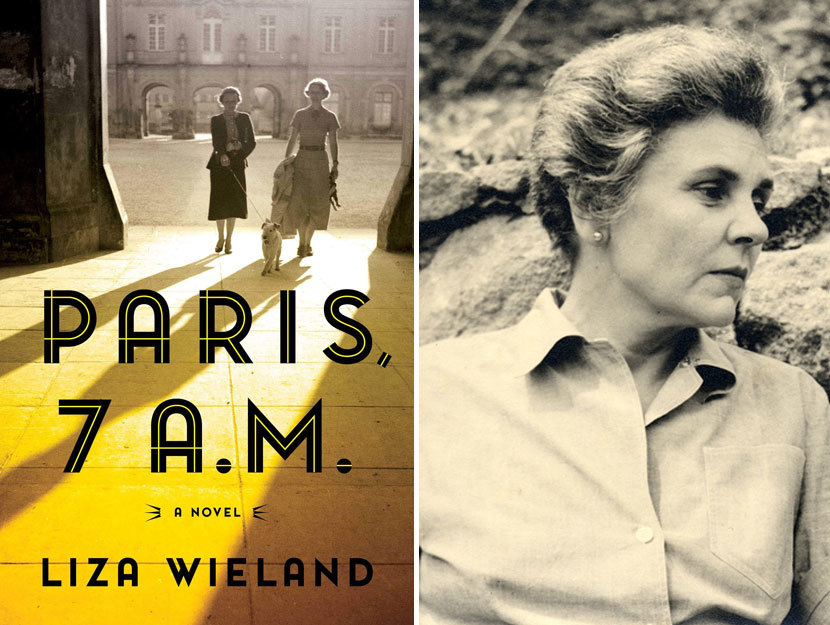

Our latest guest blog post by a contemporary writer comes to us from North Carolina–based author Liza Wieland, whose latest novel, Paris, 7 A.M., has just been published by Simon & Schuster. In Paris, 7 A.M. Wieland sets herself the dual challenge of not only writing a work of historical fiction but also of entering the sensibility of a major American poet. The novel recreates three weeks in June 1937 when the young Elizabeth Bishop was visiting Paris—a period Bishop never recorded in her journal, which means that it has remained largely a mystery to her biographers.

The novelist Madison Smart Bell says Paris, 7 A.M. “captures a sensibility that is believable as Bishop’s, complete with its sometimes acerbic lucidity, its wit, and crystalline precision of mind.”

Below, Wieland traces the complex literary lineage underlying her novel.

Paris, 7 A.M. began in earnest with my discovery that three weeks Elizabeth Bishop spent in Paris were unaccounted for in her journals. What had she been like then, in her twenties, so private and so lonely at the same time? Trying to figure out so much—how to be a writer, and what kind, whom to love, where to live—how had she navigated a foreign country and the growing threat of World War II?

Elizabeth Bishop, of course, brought me to this novel, but so did several other poets.

I discovered Bishop’s last volume of poems, Geography III, at the Rizzoli bookstore in the newly constructed CNN center in Atlanta, Georgia, where I mostly grew up. What I immediately loved about the book was the epigraph, those plain, stern quotations from what sounded to this Catholic girl like a catechism.

What is Geography?

A description of the earth’s surface.

What is the Earth?

The planet or body on which we live.

[. . .]

Of what is the Earth’s surface composed?

Land and water.

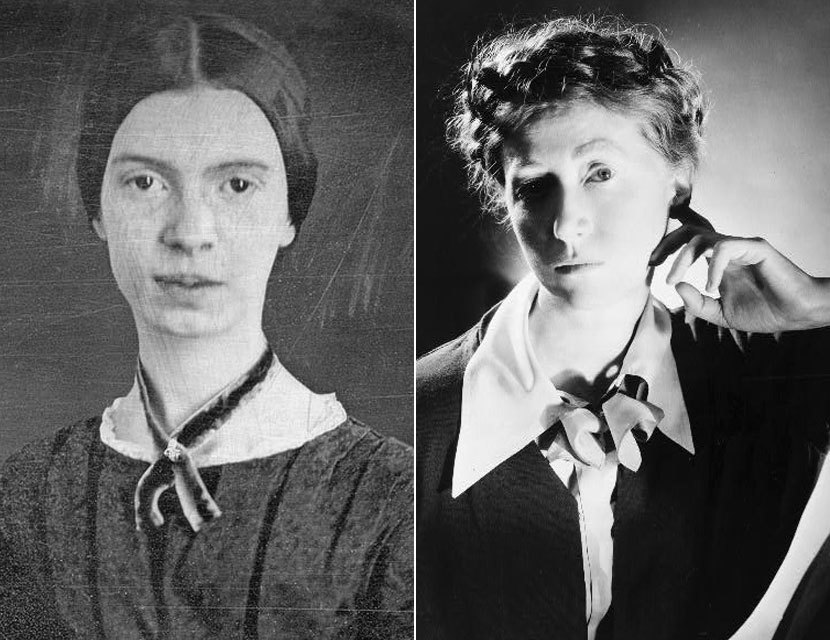

I remember that I found the book intimidating in its slightness. If poems are language that is just this side of silence, if poems are about what can barely be spoken at all, then this brevity, this restraint must be genius. “One Art,” “Crusoe in England,” and “In the Waiting Room,” poems so utterly calm about the losses and dangers they explored, frightened me deeply. But I saw in Bishop what I already loved about Emily Dickinson: a sensibility and a poetics so unusual as to be almost otherworldly.

I read Emily Dickinson for the first time in tenth grade and, as the poet herself describes feeling in the presence of poetry, the top of my head was taken off, so different and unruly were these poems (and yet they scanned perfectly!). Years later, I wrote a dissertation on the ways that Dickinson’s poems exist between the dangers of wilderness and the safety of home, and Bishop’s poems about travel became the coda. I was exploring a sort of indeterminate space—a place that is both in the world and not in the world. Some of Bishop’s poems seem to move through that same space. There’s often a feeling of disorientation and dislocation, of being a stranger in a strange land.

Ezra Pound was the first poet I ever studied in depth (though I was already deeply fascinated by Dickinson), learning a great deal about image and, particularly in The Pisan Cantos, about the intersection of history and literary art. Lines from Canto 81, written about Pound’s experience imprisoned in an open cage in Pisa, Italy, have stayed in my mind for forty years:

What thou lov’st well remains,

the rest is dross

What thou lov’st well shall not be reft from thee

What thou lov’st well is thy true heritage

Bishop’s visits to Pound in the asylum at St. Elizabeths in Washington, D.C., are memorialized in her poem “Visits to St. Elizabeths,” modeled on the children’s add-on poem “The House that Jack Built.” The elderly Pound is a character in two of the stories in my 2011 collection Quickening.

Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop were great friends and a study in contrasts, he effusive (manic during periods of illness) and sometimes so autobiographical as to be cringe-worthy, she reserved and private (I imagine them as a twentieth-century Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson in this way). The collected letters between Lowell and Bishop, Words in Air, edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton, is a deeply engaging testament to the richness and complexity of their relationship, and also a chronicle of their poetic influences.

Marianne Moore is perhaps as important as anyone in the development of Bishop’s style and perhaps Bishop’s deepest early connection to poetry, guiding the younger poet toward becoming a “literalist of the imagination.” It was interesting and instructive for me to compare Moore’s 1918 poem “The Fish” to Bishop’s poem of the same name. The letters they exchanged—collected in One Art, published in 1994 and edited by Robert Giroux—are a fascinating study of Moore’s influence on Bishop—and the limits of that influence.

Mary Oliver died this past January, as Paris, 7 A.M. was going through the last round of edits. Though they are different in style and tone, I have long imagined Elizabeth Bishop and Mary Oliver enjoying each other’s company (I recently read that Oliver somehow came to be in possession of Bishop’s handmade tea strainer from Brazil) because their poems are full of the kinds of questions they might have asked each other. In my favorite book of Oliver’s, American Primitive, I hear echoes of some of Bishop’s poems. If Elizabeth Bishop had lived into her eighties, as Mary Oliver did, I wonder whether her last book of poems might have borne a certain similarity to Oliver’s Felicity, published in 2015.

The author of seven works of fiction and a volume of poems, Liza Wieland has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Christopher Isherwood Foundation, and the North Carolina Arts Council. She is the 2017 winner of the Robert Penn Warren Prize from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. Her 2008 novel A Watch of Nightingales won the Michigan Literary Fiction Award, and her 2015 novel Land of Enchantment was a longlist finalist for the 2016 Chautauqua Prize. Wieland is a professor in the English department at East Carolina University.