Are we ready to reconsider all our assumptions about American culture in the 1940s? Published last year by Columbia University Press, George Hutchinson’s Facing the Abyss: American Literature and Culture in the 1940s is a sweeping, revelatory, and bracingly argumentative survey of the tumultuous decade that begins with America finally emerging from the Depression and ends with it rent by Cold War paranoia and poised on the brink of new foreign conflicts.

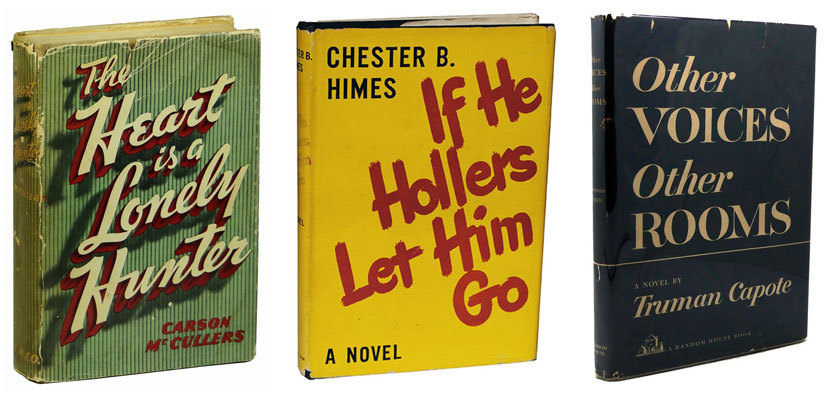

This is an overview of the 1940s that dispenses with any catchphrases about “the good war” or “the greatest generation.” In Hutchinson’s telling, the era of the atom bomb and the concentration camp gives rise to an American literature whose “dominant emotion is a new sense of dread, a haunting sensation of evil both without and within.” But it is also a literature that offers an unprecedented prominence to hitherto ignored or obscured minority viewpoints, thanks to the emergence of talents who are as different from one another as Carson McCullers and Chester Himes, Ann Petry and Muriel Rukeyser—writers who share, at the same time, a universalizing impulse that insists on the validity of individual experience.

Hutchinson’s generous, wide-angle approach can accommodate, within the space of a few pages, the thinking of émigré Frankfurt School intellectuals and the graphic impact of Bob Kane’s Batman comics. A long late chapter, “Ecology and Culture,” is especially illuminating as it traces the development of a new ecological consciousness not only in writers commonly associated with wilderness, such as the conservationist Aldo Leopold and the William Faulkner who gave us “The Bear,” but also those focused on urban settings, like Richard Wright and Lewis Mumford.

George Hutchison is the Newton C. Farr Professor of American Culture in the Department of English at Cornell University and the author of The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White (1996) and In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line (2006).

Via email, Hutchison answered a few questions we had after reading Facing the Abyss.

Library of America: In your opening pages, you write that “a fundamental and paradoxical finding of this book is that . . . cultural forms tend toward recurrence, despite previously unimaginable changes.” The implication is that the phenomena you describe both manifested themselves earlier in American culture and would also come back, however altered, in later decades. Can you elaborate on that idea?

George Hutchinson: My point here has to do with the recursiveness of cultural history, how certain forms and intellectual emphases never fully disappear but remain embedded in habit, memory, and social life even when they have gone out of favor or been submerged. Under certain circumstances, they regain their prior force, though with a difference. Think of Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction, for example, and how they seem to be echoed in more recent American cultural history, the reactionary strains of American culture that never die.

I am struck by how certain central energies of what used to be called the American Renaissance—its experimentalism, its emphasis on process, for example—have recurred through American history. It’s not a coincidence that F. O. Matthiessen’s magisterial work on that period came out on the verge of World War II and that many strains of the culture of the 1850s can be found playing out in the 1940s, as I believe they also did in the 1910s and 1920s, when the work of Melville was revived and Whitman gained status outside the academy as a poet and, to some, a prophet. Too often we are impressed by the drama of radical change and thus miss the tidal quality of cultural history, its convective energies, so to speak.

LOA: One of the major themes in Facing the Abyss is how many writers of one marginalized group—whether they were African American, Jewish, gay, lesbian, or “queer”—found common cause with members of the other marginalized groups. How successful were they in reaching across social categories, and do any of these attempted alliances have consequences for later generations?

Hutchinson: This was one of the real discoveries for me in the process of researching the book. Certainly, within the literary culture the authors did succeed in reaching across social categories, and I hope this finding comes across in the book. They spoke to each other, and within their work often dealt with multiple forms of subjection and oppression simultaneously. It is also striking how often, say, African American authors wrote work not focused on “black experience” (though this work is rarely discussed today), and how many white authors attacked racism and “whiteness” itself—that is, the unexamined presumptions of white “identity” as the model of human identity. These authors often supported one another.

The anti-communist hysteria of the 1950s broke up a lot of these interconnections. Many of the currents of critique of American culture today associated with identity politics (for instance, “whiteness studies,” critiques of “heteronormativity”) are fully present in the 1940s, but they are presented in the form of an aspiration to universalism rather than the particularist identity politics we see today, which is outmatched by the identity politics of our current president and his most devoted supporters. As I point out in the book, the heroes of identity politics in the 1940s were Hitler, Hirohito, Mussolini, southern senators, and the “America First” movement with its celebrity mouthpiece Charles Lindbergh. The writers I find most compelling in the 1940s are those who are conscious of their own tendencies toward magnification of the self and reduction of the other to an abstraction. As Marianne Moore wrote, “There never was a war that was not inward.”

LOA: You focus on a handful of 1940s novels by African American writers that feature white protagonists—Ann Petry’s Country Place (1947), Willard Motley’s Knock on Any Door (1947), and Zora Neale Hurston’s Seraph on the Suwanee (1948). Motley’s novel was a best seller (and even became a Hollywood movie starring Humphrey Bogart), but these books simply aren’t that well known today. Are we still not sure what to make of these fictions that cross the lines of identity?

Hutchinson: Yes. There just isn’t much interest in them. It seems that we want black artists to “represent” or “perform” blackness. Toni Morrison has complained about this in a recent essay; she asked that an interviewer not focus on race in the interview, as she wanted to talk more about the how of her writing, so to speak—the formal and stylistic choices, and so on—but the interview nonetheless went straight to questions of blackness.

One factor here, in the academy, is the job market. There is little to no encouragement to address such work, unless one devises ingenious theories to account for it in a way that fits it back into the categories we take for granted. My eldest son is an African American artist. He majored in sound at the Art Institute of Chicago and was deeply engaged in electronic music, which was actually pioneered by African Americans but soon became identified as primarily “white.” In his visual art, similarly, he was most moved by abstraction and little of his work dealt in any definable way with “black” subject matter or a distinctively racial visual vocabulary. He found it very difficult to gain attention until he started producing more recognizably black art that could be included in exhibits focused on such.

Conversely, white artists get pilloried when suspected of “appropriating” black subject matter or styles. If the work is bad, if it rehashes old stereotypes and so forth, or is disrespectful, it should of course be criticized on those grounds, but the discourse of appropriation can become simply a matter of protecting turf and is symptomatic of the larger problem rather than a movement toward a solution.

LOA: Facing the Abyss makes it clear that many of the liberating creative energies set loose in 1940s American culture were tamed, actively suppressed, or otherwise dispelled by the early 1950s. How do you account for this apparent triumph of reaction? Could that be a subject for another book?

Hutchinson: This brings us back to my notion of the recursiveness of cultural history. My sense is that the fear inspired by the Cold War, which became frigid with Mao’s triumph in China, the start of the Korean War, the USSR’s detonation of an atomic bomb, and so forth, allowed the reactionary tendencies in American society (which are ever-present) to resurface. In an atmosphere of near-hysteria, following upon the trauma of the Depression and the war, they took control of the national narrative. The pressures for normativity seem to have functioned as a security blanket for many Americans even as they had the opposite effect for national minorities, including political minorities such as Marxists and so-called fellow-travelers.

As for another book, I think there is a lot of scholarship about the Cold War; in fact, one of the instigations for my book was the sense that the late 1940s had been too hastily folded into the Cold War narrative by scholars, while the culture of the early 1940s had been overshadowed by the dramatic military history and treatments of popular films. I was interested in exploring the liminality of the period precisely because twentieth-century cultural history had been so firmly divided between pre-1945 and post-1945, leaving the ’40s in limbo.

For my next book, I’ve been talking to an editor about a more wide-ranging treatment of American literature drawing out the implications of my last three books, about how the great variety of social positions from which American writers have entered the literary sphere, which distinguishes American literature for most of its history, has repeatedly inspired literary invention. The racial culture peculiar to the United States, particularly its black-white divide, has likewise been a major factor, even an identifying thread. But that culture paradoxically assimilates even as it divides. Through its very divisions it also instigates fetishization and transgression. Authors meet in the sphere of the literary, which—as I write in Facing the Abyss—cannot be so easily mapped, because authors are drawn to boundaries, to express the inexpressible; in seeking new resources of language, they encounter and respond to one another.

In recent years, this emphasis on the cultural ecology of the United States has been lost in the academy as an emphasis on diaspora and transnationalism has been all the rage; but that direction (which was salutary) has about exhausted its formative energy at this point. Besides, we can see clearly how the “national” never went away in the general culture, nor even in the very way diasporas were defined according to contemporary American cultural assumptions. It behooves us to pay attention to the resources at hand. We might inevitably categorize authors in separate boxes so that we can analyze particular features of their work, but these boxes should never be more than provisional. In high school, you might be taught to dissect a frog to find out how each aspect of its anatomy works, but in the process you lose the frog.