By Max Rudin

President and Publisher, Library of America

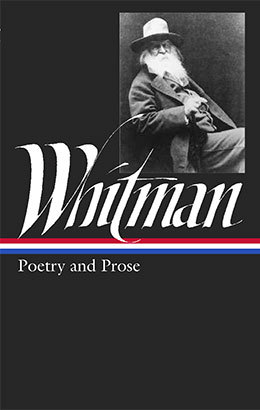

Today marks the bicentennial of Walt Whitman (1819–1892), whose Poetry and Prose was one of the first four volumes published in the Library of America series in 1982, and may still be the one closest to my heart. Looking out my office window at midtown Manhattan, I find it not too hard to imagine the streets Whitman once sauntered through, absorbing the “blab of the pave” of the great, modernizing city bustling with new immigrants, the recognizable ancestor of today’s heterogeneous America. Two hundred years on, there is fresh wonder in the thrilling and exuberant poetic vision of American democracy Whitman discovered and celebrated. Here, as my 200th birthday tribute, is a true story about the mystery of literary genius.

In 1851, Walter Whitman, then 32 years old and living with his parents and several siblings on Prince Street in Brooklyn, went into the house building business. There was a construction boom on, the city was transforming itself, and he was hoping to cash in on the rapid expansion that was changing the face of both Brooklyn and Manhattan.

Born in Huntington Township on Long Island, Whitman had grown up in a still rural Brooklyn, attending its one public school at Concord and Adams. (His teacher there, learning that Whitman had become a famous poet, remarked “We need never be discouraged over anyone.”) He went to work early, as a printer’s apprentice, a frustrated schoolteacher, and then as editor of a staggering variety of newspapers in Manhattan and Brooklyn. His longest stint was as editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the Democratic party’s organ in Kings County. His office at 30 Fulton Street had a good view of the busy Fulton ferry; after work he often took it into Manhattan, sometimes to see the opera. On warm days he went for a short swim at Gray’s Swimming Baths at the foot of Fulton St. He especially liked the East Brooklyn stages, pulled by horses, which ran southwest to Fort Greene and Greenwood Cemetery. Apart from journalism, he wrote some poems and sentimental short stories and a melodramatic novel about the evils of alcohol.

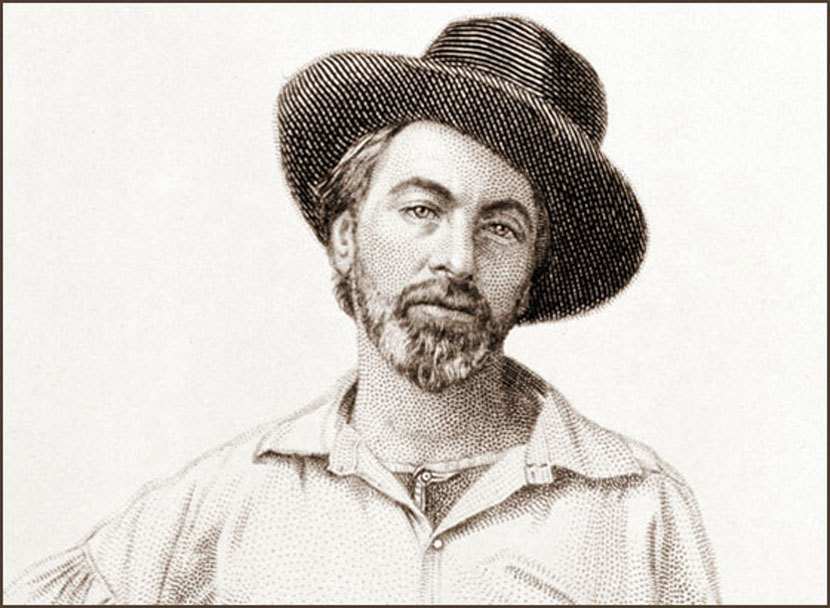

So there was nothing to prepare anyone for the astonishing metamorphosis he underwent during the four years it took his house building business to fail. Something extraordinary had happened. In early spring 1855 Whitman walked every morning to a redbrick shop on the corner of Fulton and Cranberry Streets, where he sat at a corner table as the sheets of a book he had written came off the press. Leaves of Grass, a volume that was to change American and world poetry, was published in May. In it, the failed Brooklyn journalist and carpenter Walter Whitman was himself transformed into “Walt Whitman, a kosmos, of Manhattan the son.” The startlingly beautiful, rude, extravagant, sensuous poetic lines, hewn and laid as strong and true as a carpenter’s crossbeams, delivered on a spectacular claim: “Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems.”

Whitman’s preface stated, “the United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem,” and he prophesied the coming of an American poet who would write “the great psalm of the republic.” He was echoing the literary patriotism in the air in those days, which called for an original native literature free of European influences. One of the ironies of our literary history is that when the new American literature appeared in 1855, few seemed to notice. Though discouraged, Whitman had a strong sense of mission and the support of a small circle of advocates; he continued to revise and reissue his leaves until his death. The largest royalties he ever earned from the book were $1,439 in 1882, after it was banned in Boston.

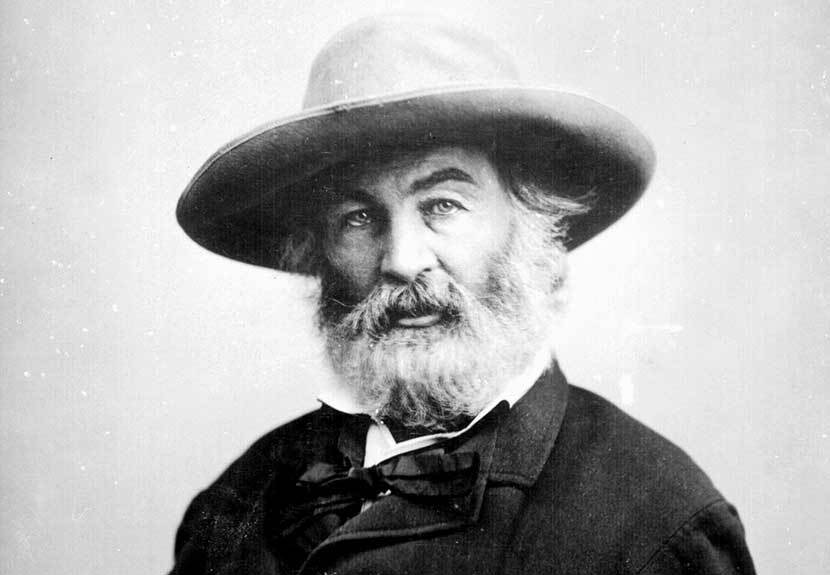

In later years, after Whitman had left New York—first for Civil War battlefields and a job in Washington, D.C., then to settle in Camden, New Jersey—he reflected on the gestation of his masterpiece: “Remember,” he said, “the book arose out of my life in Brooklyn and New York from 1838 to 1853, absorbing a million people, for fifteen years with an intimacy, an eagerness, an abandon, probably never equalled.” The energies Whitman absorbed during those years were thrown off by a city that changed in his lifetime from a Dutch Knickerbocker town into a modern commercial metropolis. When Whitman was born in 1819, two months before Herman Melville, Manhattan ran from the Battery to 14th Street and had about 120,000 people; Brooklyn had about 4,000. You could stand on Brooklyn Heights (then called Clover Hill) and look clear across Manhattan over the Hudson River to New Jersey; there were pigs and chickens in the unpaved streets which were so dark at night you had to find your way with lanterns. By his death in 1891, thanks to an enormous influx of immigrants, Brooklyn had well over a quarter million people. Thirteen ferries and a spectacular bridge connected it to Manhattan, where a million and a half people lived from the Battery to the northern tip of the island, and traveled in elevated railways.

Whitman’s imagination flirted with the West, but he’s really the poet of this new city—Broadway is more important to him than the open road, the blab of the pave, as he called it, more than the song of the broadaxe. Herman Melville brooded on the alienation and indifference he found in the great new commercial capital; Whitman, without excluding urban casualties from his sympathetic regard, celebrated its sights and sounds, its energy and streaming crowds. Leaves of Grass is filled with crowds of people, the sounds and scenes of a city still building itself, the rapidly shifting glimpses of life caught by a walker in the city streets—from Broadway stage drivers, wealthy promenaders in Central Park, political meeting and parades, the theatre and Italian opera, to opium addicts, prostitutes, and “venerealees.” City life and city dwellers test Walt’s powers of democratic sympathy and identification, and his book is a record of that experience.

And there’s the character of “Walt” himself, who owes more to nineteenth-century New York City life than we usually recognize. Contemporary reviewers noticed it at once: one called the poet “a compound of New England transcendentalist and New York rowdy.” The rowdies, also known as “roughs” or “loafers,” were gang members and street loungers who roved New York’s slums. When Walt calls himself “one of the roughs” or says “I lean and loaf at my ease,” he’s casting himself as a street tough, to assume a radically democratic street-level perspective on the new America—much as Melville did with another New York type, Ishmael the sailor. Whitman also admired another New York street subculture, the tough, proud volunteer firemen known as “Bowery b’hoys,” who were famous for their slang. “So long!” was a Bowery expression he took for a poem title.

Wicked, reckless, slangy, vigorous, independent, cocky, the Walt of Leaves of Grass is a kind of sublimated version of characters found on the uncouth, crime-haunted streets of modernizing New York. Some found this identification absurd, especially since it seemed to extend to the poet himself, who gave up his dandified vest, polished cane and beard for the open shirt, rough rumpled pants, and round cocked hat of the working man. “A poseur of truly colossal proportions,” one observer called him, “to whom playing a part had long before become so habitual that he ceased to be conscious that he was doing it.” What they didn’t see was that Whitman, “lover of populous pavements / Dweller in Mannahatta my city,” had found on the streets of Brooklyn and New York not just a “part” but a poetic identity that would forever transform American writing: a character, a subject, and new form of poetry through which to celebrate the possibilities of a new America both fiercely individualistic and electrifying collective.