This June, for the seventy-fifth anniversary of D-Day, Library of America releases Cornelius Ryan: The Longest Day, A Bridge Too Far, a new collector’s edition of two classic narratives of World War II. In these books Ryan pioneered a new kind of democratic military history, combining the individual stories of top brass and ordinary soldiers, combatants and civilians, into pointillist masterpieces—novelistic epics told on a human scale.

The new volume also collects seventeen of Ryan’s wartime dispatches for the London Daily Telegraph, including his eyewitness account of D-Day as seen from an American bomber; magazine stories that supplement The Longest Day; revealing letters to publishers; and samples of the research questionnaires he sent to veterans. It restores the full-color endpaper maps from the 1959 edition of The Longest Day, and includes an introduction, a chronology of Ryan’s life and career, explanatory endnotes, eighty-eight pages of photographs, many from Ryan’s personal collection, and twelve black and white maps.

The editor of Library of America’s Ryan edition is journalist and historian Rick Atkinson, whose books include the acclaimed Liberation Trilogy about World War II: An Army at Dawn, which won the Pulitzer Prize for History, The Day of Battle, and The Guns at Last Light, as well as The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775–1777, the first volume in a planned Revolution Trilogy.

Via email, Atkinson discussed his longstanding admiration for Ryan’s work and why, out of so many histories of World War, Ryan’s have endured.

Library of America: Thousands of books have been written about World War II. Why are these two books by Cornelius Ryan classics? Why are they still worth reading?

Rick Atkinson: These two books are still illuminating, and at times electrifying, because the extraordinary research that went into Ryan’s narrative provides us with a vivid, visceral depiction of these two battles, among the greatest battles in modern warfare.

LOA: A. J. Liebling, who memorably reported on the war for The New Yorker, once wrote: “Books about war fall into two classes—those about what it was like and those about what happened.” How do Ryan’s narratives fit into this scheme?

Atkinson: With all due respect to the great Liebling, these two categories are not mutually exclusive. Cornelius Ryan proves the point. His battle narratives certainly give us a tactile, auditory, visual, and olfactory sense of what it was like, and his sleek storytelling tells us very clearly what happened. Can’t do better than that as a military historian, in my estimation.

LOA: Ryan was a war correspondent for The Daily Telegraph in 1944–45, and an editor at Collier’s magazine for much of the 1950s. How did his journalistic background influence his writing about war?

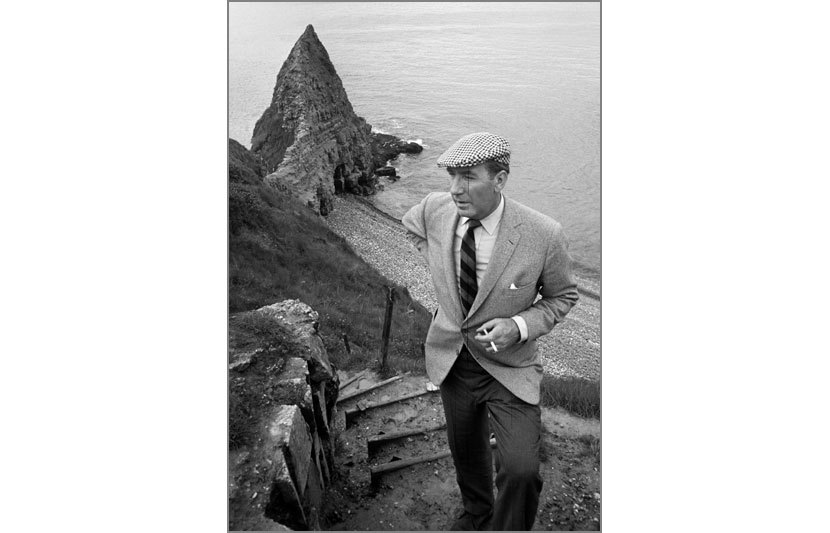

Atkinson: As a former hack myself, I can see clearly how Ryan’s long experience as a newspaper and magazine journalist informs his narrative writing. We see it in his meticulous reporting, in his commitment to accuracy, in his ability to tell the story compactly, and in his recognition that making the tale accessible to a reader is paramount. Until his death, he remained one of the great reporters, which is why the single-word epitaph on his headstone—Reporter—is apt.

LOA: Do you have a favorite scene in The Longest Day? In A Bridge Too Far? By “favorite” we mean exceptionally well-written and/or memorable—passages that really convey the essence of what he was trying to do.

Atkinson: In The Longest Day, I very much admire the way he essentially bookends the story with the camera’s lens focused on Erwin Rommel, the senior German commander at Normandy. The brushstrokes of detail in describing Rommel’s return to La Roche Guyon, his headquarters on the Seine, are masterful, and contribute to the suspense he builds as the invasion draws near. I’ve been to that chateau, with a copy of Ryan’s description in my pocket.

In A Bridge Too Far, I love the scene in the theater where General Horrocks, the senior British tactical commander, reviews the plan for Market Garden a final time. The reader feels as though he’s sitting in the audience as this magnificent, doomed moment plays out.

LOA: How has the success of Ryan’s books influenced the subsequent writing of military history?

Atkinson: Every scribbler who has tried to write narrative military history in the past half-century owes some debt to Ryan. He demonstrated that a non-academic could write riveting narratives while observing the appropriate conventions of academic history. His influence on me personally is deep and enduring.

Read Library of America’s interview with Rick Atkinson on The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775–1777 here.