As part of our ongoing commemoration of Walt Whitman’s 200th birthday on May 31, 2019, we present the following excerpt from our 2004 special publication American Writers at Home by J. D. McClatchy and Erica Lennard, in which McClatchy (1945–2018), a poet, educator, and the editor of several Library of America volumes of poetry, turns his attention on the row house in Camden, New Jersey, where Whitman lived from 1884 until his death in 1892.

By J. D. McClatchy

Text copyright © 2004 J. D. McClatchy. Photographs copyright © 2004 Erica Lennard.

At Whitman’s funeral, on March 30, 1892, as his disciples gathered around his coffin under a small open tent in the Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, the poet was remembered less as a poet than as a philosopher. His mourners knew, of course, that he was the great original, the poet who had swept all the stuffy traditions aside and boldly created a poetry of sublime intentions and inclusive range. He was the poet whose words, at the very start, Ralph Waldo Emerson had called “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.” He inspired writers around the world, and his influence in his own country has, happily, never diminished, even as its intense and majestic and tender monumentality have come to define the American imagination itself. And indeed a section of “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d” was read out at the service. But far more time was taken up memorializing Whitman’s messianic role as The Cosmic Democrat, the Liberator. He was recalled, in the words of one speaker that afternoon, as “arduous, contentious, undissuadable and infinitely loving. He came bearing the burden of a Gospel, the Gospel of the Individual Man; he came teaching that the soul is not more than the body, and that the body is not more than the soul; and that nothing, not God himself, is greater to one than one’s self is.” And to exemplify his universality, passages were read out from Confucius and Plato, from the Buddha and the Koran. And when a passage from the New Testament was read it was thought singularly appropriate for a man of such infinite sympathies: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

A visitor to Whitman’s house in Camden today should keep those words in mind. Camden today is a blasted city, and 328 Mickle Street is in a desolate part of town. Directly across the street is an ugly and massive county jail. The garden behind the house is fenced in with barbed wire. But the little clapboard row house stands there pluckily, and the man who once lived there had in his own day cast his poetic gaze lovingly on “the crazed, prisoners in jail, the horrible, rank, malignant.”

Whitman felt entirely at home on Mickle Street, and when he moved there in 1884, just a couple of blocks from the Camden waterfront, with a vista of Philadelphia steeples across the broad Delaware River, it might have reminded him of Brooklyn when he lived there in the 1840s and 50s, working as a printer and reporter. Camden was a working-class city, a thriving transportation hub busy with shipping, railroads, and ferries. And a photograph of Mickle Street when Whitman lived there shows it tree-lined, a neat parade of brick row houses on either side. But in fact, the poet’s friends considered it a poor choice. The rail depots made it a noisy part of town, and a guano factory across the river made it foul-smelling as well. Elizabeth Keller, who helped care for Whitman toward the end of his life, remembered the house as “sadly out of repair, and decidedly the poorest tenement on the block.” There was an “uninterrupted racket day and night,” and the new electric streetlamp, just outside the poet’s bedroom window, was an intrusive annoyance. The block “was anything but inviting, and the locality was one that few would choose to live in.” The staircase and hallways, she complained, were narrow, the kitchen more like the cabin of a ship, and Whitman’s bedroom a “hillock of débris.” Whitman himself, of course, loved it. He called it his “little old shanty” or “my nook,” and would sit all day by an open window downstairs, chatting with passersby, listening to his housekeeper’s canary. Above all, it was his, the first and only house he ever owned, a refuge from the wide world and a shrine where he could receive its homage. (A letter from England, addressed only to “Walt Whitman, America,” arrived at Mickle Street without delay.) But it was a series of bitter trials that had brought him there.

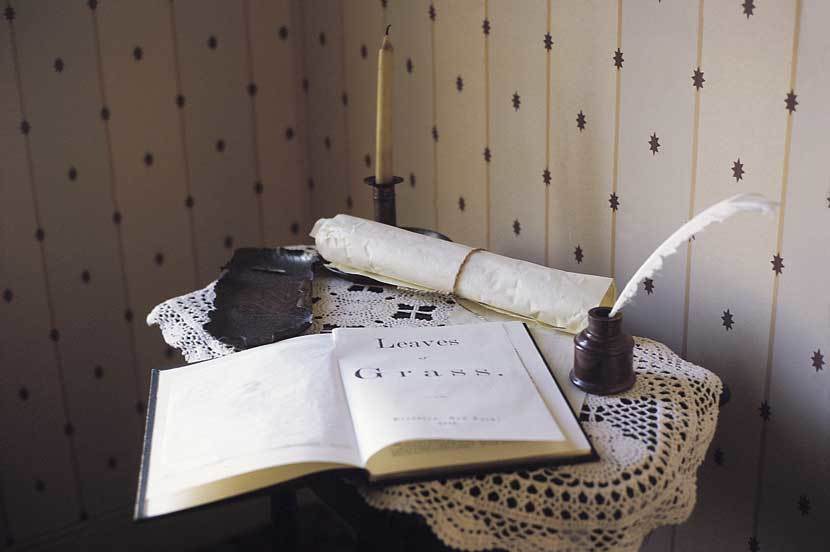

In July 1855, twelve untitled poems and a prose preface appeared in a book called Leaves of Grass. Its binding was elaborately tooled, and inside was a lithograph of the author, his head jauntily cocked above an open shirt . . . “Walt Whitman, a kosmos, one of the roughs.” There were 795 copies printed, and Whitman himself wrote three unsigned reviews of the book, all of them raves. It was a commercial failure, and a personal humiliation, but he persisted. The very next year, he published a new and expanded edition, and began to envision “the Great Construction of the New Bible,” an ideal Leaves of Grass that would inspirit the nation. But then the Civil War wrought its havoc and shattered his utopian dreams. Hearing that his brother George has been wounded in Virginia, Whitman rushed to the front to care for him. Getting off the train near Fredericksburg, the first thing he saw, as he wrote to his mother, “was a heap of feet, arms, legs, &c. under a tree in front of a hospital.” He found his brother, but much more besides: “I go around from one case to another. I do not see that I do much good to these wounded and dying; but I cannot leave them.” He eventually settled in Washington and tended to the patients in military hospitals, while supporting himself doing part-time clerical work in the Army Paymaster’s office. All the while, he wrote down his impressions of young soldiers and their fates in a book he later published as Specimen Days, the most harrowing and moving document to have emerged from those bloody years. The war shook Whitman to the core and left him a weakened man. He accepted a post at the Department of the Interior in 1865, but was fired by Secretary James Harlan, who came upon a copy of Leaves of Grass in Whitman’s office desk and considered it obscene. When his hero Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, he knew that the country’s convulsions had ruined its best hopes. Still, he kept publishing, and attracted notice from around the world for the humane power of his words. But he was stalked by illness, and in January, 1873, suffered a paralytic stroke. A few months later, hearing from his brother George, a pipe inspector in Camden, that their mother was sinking, he rushed to her side. She died three days later. He had meant to return to Washington, but he lingered. He liked his sister-in-law, Louisa, he liked the proximity to cosmopolitan Philadelphia as well as the restorative New Jersey countryside.

In 1882, not long after a new edition of Leaves of Grass was published in Boston, the city’s district attorney warned that he considered certain poems in the book to be filthy, and the publisher withdrew the book—which, predictably, so increased sales elsewhere that for the first time in his life Whitman came into some money. That year his royalties were $1439. The year before, they had amounted to just $25. The timing was fortuitous, because the next year, his brother George moved to Burlington, New Jersey, and the poet was uprooted. In March of 1884, Whitman moved into 328 Mickle Street, and a month later purchased it from Rebecca Jane Hare, a widowed dressmaker, for $1750.

The house is something of a rarity, not because of its architectural style-—a mongrel amalgamation of details from Greek Revival and Colonial Revival—but because it is constructed of wood. It was built in 1848, the first house on the block, and five years later the city of Camden enacted an ordinance forbidding new houses made of wood. So, while all its neighbors are brick, Whitman’s new house may have appealed to him—who so loved long tramps through the fields or to swim in the Jersey ponds—precisely because of its rustic appearance.

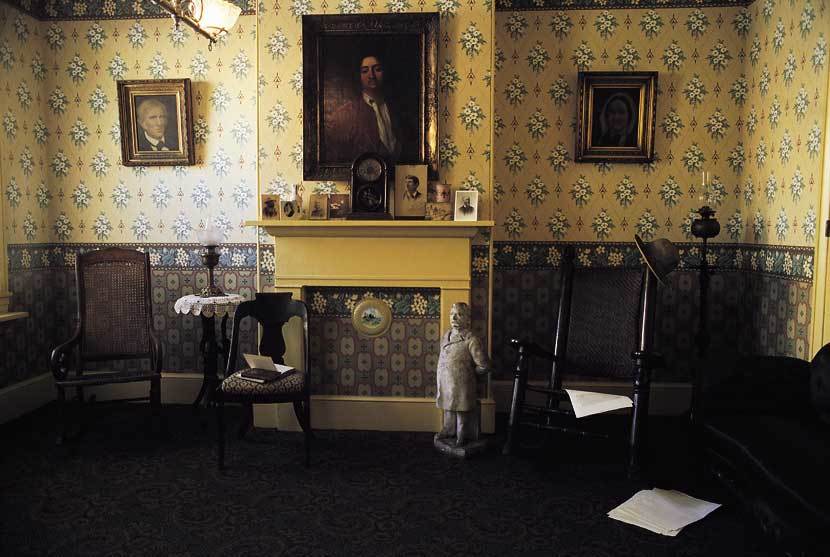

His first housekeeper, Mrs. Lay—his increasing lameness meant that he required help—came to displease him, and the next year she was replaced by the devoted Mary Davis, who fussed over him, made his shirts, and tended to his appearance. She would pick him up at the ferry and accompany him on the omnibus, and best of all, would bring him his favorite dinner of stewed oysters and toasted graham bread and beer. In his first years on Mickle Street, he would take his meals in the front parlor, where he would often spend the day at a cluttered table near the window, his coach dog, Watch, curled at the foot of his rattan rocker. The house had gas lighting and running water, and its wallpaper and carpets have the florid look of the late Victorian era. On either side of the fireplace were oil portraits of his parents, and over the mantel a genre painting of a hearty burgher Whitman always referred to as “the Hollander.” Littering the mantel were the photo-cards left by visitors and admirers. The back parlor stood on the other side of sliding doors that could be opened up for receptions. Horsehair chairs flank walnut bookcases filled with editions of Shakespeare and Scott, Dante and Emerson, George Sand and Epictetus. Beyond are the kitchen, and outside a back garden with annuals and herbs, hydrangea, a small pergola entwined with wisteria, and an outhouse. In the rear of the upper floor was Mrs. Davis’s room, and a room that contained Whitman’s copper-lined bathtub. Closer to the front was a small bedroom for Warren Fritzinger, Mary Davis’s foster son, who worked as Whitman’s nurse in the final years. And at the front of the house was Whitman’s own bedroom. When he could no longer manage the stairs, the poet would spend all his days in this room. He finished his last collections here, November Boughs (1888) and Good-Bye my Fancy (1891), and oversaw the final, so-called “deathbed” edition of Leaves of Grass, as well as his Complete Prose Works. These were the years he endeavored to put the finishing touches on his legend, and it is interesting to note that in 1890 he arranged to have a “burial house” of his own design constructed in the Harleigh Cemetery. The contract with P. Reinhalter & Co. stipulated that the platform, walls, and cap and roof all be of the best Quincy, Massachusetts, granite, and that the eight catacombs within (where later his parents, his brother George, and his wife and an infant son of theirs, plus Whitman’s mentally retarded brother Eddy were all re-interred) be made of Pennsylvania blue marble. For this mausoleum, he agreed to pay $4,678, more than double the cost of his house.

Whitman himself, in some of his very last writings, left vivid descriptions of his bedroom, where he would sit in a huge armchair, with a black and silver wolf-hide spread over its back, and poke with his cane through the “deep litter of books, papers, magazines, thrown-down letters and circulars, rejected manuscripts, memoranda, bits of light or strong twine, a bundle to be ‘express’d,’ and two or three venerable scrap books.” Against the walls were trunks of his papers, piles of books, and a strew of printer’s proofs and slips. In the center of the room were two large tables covered with papers and writing materials, along with “several glass and china vessels or jars, some with cologne-water, others with real honey, granulated sugar, a large bunch of beautiful fresh yellow chrysanthemums, some letters and envelope papers ready for the post office, many photographs and a hundred indescribable things besides.” A year before his death, he wrote that “I keep generally buoyant spirits, write often as there comes any lull in physical sufferings, get in the sun and down to the river whenever I can.” Above all, he said, “I retain my heart’s and soul’s unmitigated faith not only in their own original literary plans, but in the essential bulk of American humanity east and west, north and south, city and country, through thick and thin, to the last.” He was the poet who believed that in writing the “Song of Myself,” he could encompass all of humanity:

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. . . .Do I contradict myself?

Very well then . . . I contradict myself;

I am large . . . I contain multitudes. . . .

The last scud of day holds back for me,

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any on the shadowed wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the dusk.

I depart as air . . . . I shake my white locks at the runaway sun,

I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift in lacy jags.I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.

A few months before he died, Whitman’s friends bought for him a new bed with a handsome oak headboard, and later a water mattress to ease his pain. But he remained cheerful to the end, even joking that he could remember just enough of a thing to remind him of how much was forgotten. “Here I am,” he said, “tied up at the wharf, rotting in the sun.” But he could remember his ecstatic “poems of the morning,” his vision of a spiritual and heroic America leading mankind into a future of freedom and equality, of comrades secure in their devotion to their belief in “the divine aggregate, the People.” On his last afternoon, sinking rapidly, he clutched a friend’s hand and urged him to be strong: “Keep a firm hand—stand on your own feet. Long have I kept my road—made my road: long, long! Now I am at bay—the last mile is driven: but the book—the book is safe!”