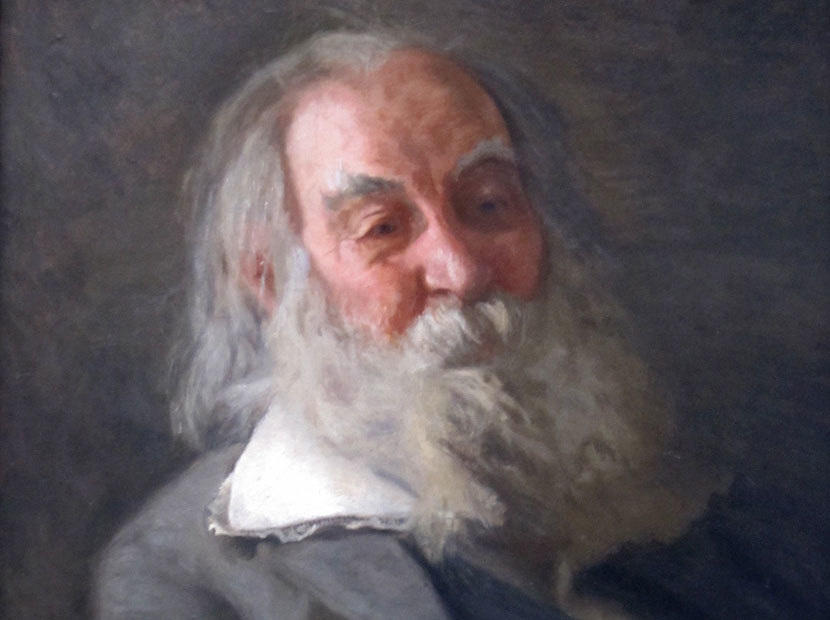

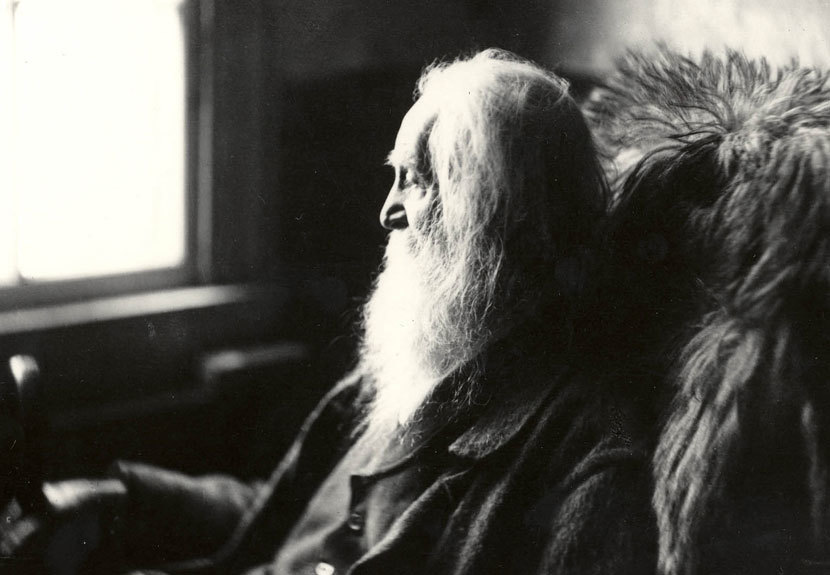

In the last few years of his life, Walt Whitman was visited almost daily at his home in Camden, New Jersey, by the young writer and social reformer Horace Traubel. Traubel transcribed his conversations with the older poet so meticulously that, when published in book form as With Walt Whitman in Camden, they came to fill nine large volumes.

Released in commemoration of Whitman’s 200th birthday on May 31 of this year, Library of America’s new special publication Walt Whitman Speaks is a one-volume “best-of” drawn from Traubel’s extensive interviews. Judicious selections by editor Brenda Wineapple convey the essence of Whitman’s late-life wit and wisdom on matters literary, political, and spiritual—in short, everything he had learned over seven decades of vigorous living.

Wineapple is the author of several works of nineteenth-century history and biography, including Ecstatic Nation, White Heat, Hawthorne: A Life, and, most recently, The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation. She previously edited John Greenleaf Whittier: Selected Poems for Library of America. Below, she discusses the editorial process behind Walt Whitman Speaks, and describes what it was like to be immersed in the company of the poet who could plausibly refer to himself as “a kosmos.”

Library of America: Walt Whitman Speaks is distilled from nine volumes, totaling several thousand pages, of original material. Did you actually work your way through all those books? What was your selection process like?

Brenda Wineapple: In order to hear Whitman’s voice, I had to read through all nine volumes even though Library of America’s wonderful editor Jim Gibbons had initially read and then highlighted what he considered the best of Whitman’s conversation. Fortunately, though, I’m an insomniac, so during many of the nights when I couldn’t sleep, I picked up the Traubel volumes and learned, as I’ve written, what excellent company Whitman can be. At the same time, and while reading the Whitman volumes during the daylight hours, I was keeping extensive notes on the sections that struck me as illuminating, witty, charming, informed, distinctive, and/or surprisingly contemporary.

I did not begin with any preconceived subjects or topics. Rather, when I finished all nine volumes, I studied my notes until I could determine how Whitman’s voice might be best served. Soon I noticed that Whitman’s recurring preoccupations—with poetry, for instance, or with other writers, or then-current events—could be gathered under various headings.

LOA: Whitman spoke knowing that Traubel was keeping a careful record of all their conversations. Do you ever have a sense, in these pages, of a writer performing for posterity?

Wineapple: Whitman was a consummate performer and his poetry—in particular his magnum opus Leaves of Grass—can be justifiably understood as an ongoing performance of the self-as-persona or protagonist. When talking with Traubel, then, Whitman seemed to be doing much the same thing: performing himself, which is not, however, an act of gimmickry or artifice. Quite the contrary: Whitman was always sincere; he was dynamic; he was unashamed and unapologetic. He wanted that recorded: the candor, the brazenness, the clarity of purpose, and of course the friendliness. So yes, he knew (or hoped) he was performing for posterity, because for him, the performance of the self was also the performance of us all and what we can be.

LOA: What most surprised you about Whitman as you rediscovered him in the Traubel conversations?

Wineapple: Perhaps what surprised me most was Whitman’s insatiable curiosity and his resilience in the face of illness and increasing infirmity. His poetry points in that direction, but to hear him interrogate Traubel about books and people and current events, I could better comprehend him as a sentient, inquiring human being, alive to experience even while confined to a closed room. Curious about the range of human experience, he sought to learn as much as he could about what various people thought, what they created, what they hoped for and sought. His interests took him to theater, which he loved; to opera, which he loved; to the great outdoors, which he loved, and to rivers and ocean and to forests but also to cities and city streets; his interests took him to novels and to politics and to science and technology, which fascinated him. He really did embrace multitudes.

And Whitman countenanced sickness and death with courage and optimism, even during his darkest days and without the consolations of institutionalized religion. He was a deeply brave man.

LOA: You’ve uncovered remarks that will strike readers as startlingly relevant to our present moment. In the section titled “America,” for instance, Whitman declares:

America must welcome all—Chinese, Irish, German, pauper or not, criminal or not—all, all, without exceptions: become an asylum for all who choose to come. We may have drifted away from this temporarily but time will bring us back. . . . Dare we deny them a home—close the doors in their face—take possession of all and fence it in and then sit down satisfied with our system—convinced that we have solved our problem? I for my part refuse to connect America with such a failure—such a tragedy, for tragedy it would be.

In interviews like this it’s customary to ask, What would historical figure X say about contemporary phenomenon Y?—but in this case it seems clear how Whitman might regard our current “national emergency.” Were you struck by other such instances?

Wineapple: Yes, definitely. Whitman is very contemporary, almost breathtakingly so. Take for instance his saying that “America means above all toleration, catholicity, welcome, freedom.” Or consider his conviction that we are part of a larger world: “I do not seem able to bring myself to love America, to desire American prosperity, at the expense of some other nation or even of all other nations.”

Or consider this: “The thing to have is the truth, not to be satisfied even with the spirit of truth, but to demand the fact itself—the divine, unaided, uncircumlocuted, unmanipulated fact, however bare, however it forbids—only in an adherence to this is the safety of history.” I could go on and on, but it’s best for readers themselves to listen to Whitman and take heed.

LOA: In the “Sex” section, Whitman boasts repeatedly of his refusal to expurgate his poetry. But a page or two later, he can seem downright coy:

I often say to myself about Calamus [i.e., the “Calamus” poems in Leaves of Grass]—perhaps it means more or less than what I thought myself—means different: perhaps I don’t know what it all means—perhaps never did know.

What do you think is going on here?

Wineapple: I think Whitman is always candid although one of his remarks may in fact contradict another one. Recall his celebrated lines in “Song of Myself”: “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself,/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.) ”

But, more seriously, it seems to me that Whitman was telling the truth to Traubel: that the “Calamus” poems could mean more or they could mean less than what he thought; they could mean different things to people who are not him. Of course, when the British writer and Whitman enthusiast John Addington Symonds urged Whitman to discuss the sexual connotation of the “Calamus” poems, Whitman responded by saying he’d fathered six children. So he knew what Symonds was asking, and he avoided answering. But avoidance is not disingenuousness. Rather, Whitman wanted to embrace multitudes as well as contain them, and in this sense, his eroticism is non-exclusive and resists—survives—overly simplistic labeling.

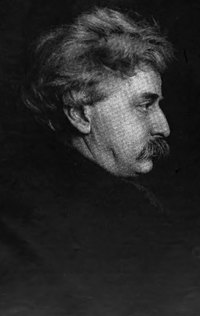

LOA: Your introduction is likely to pique readers’ interest in Whitman’s young interlocutor, Horace Traubel. What should we know about this committed socialist and humanitarian, who later won the esteem of figures like Eugene Debs, Emma Goldman, and Helen Keller?

Wineapple: Horace Traubel was an unusual man: one of Whitman’s three literary executors, he was diligent, devoted, and determined to fan the Whitman flame, which he successfully did.

But he was interesting in his own right: born in Camden, New Jersey, in youth and later, he became a committed socialist, pacifist, and activist on behalf of women’s suffrage, sexual freedom, prison reform, and animal rights. Not only did he champion Walt Whitman, whose legacy he carefully tended, but in his monthly magazine, the Conservator, he vigorously praised Zola, Upton Sinclair, Ibsen, Tolstoy, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Among his friends were Marsden Hartley, Margaret Sanger, and John Sloan. He was beloved, down-to-earth, kind, and candid. A poet whose verse echoed Whitman, he insisted that “every great artist is a partisan,” which is exactly what he was proud to be.

Read Library of America’s interview with Brenda Wineapple about her new book The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation here.