April 15, 1865: Just hours after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson becomes the nation’s “Accidental President.” The Unionist Democrat of Tennessee who had been vice president for just five-and-a-half weeks faces a war-torn, fractured country and four million people, recently enslaved, still without their full rights as citizens. How will he lead the nation forward? Will he hew close to Lincoln’s vision of “malice toward none” and “charity for all?” What will be the mechanism for reintegrating the secessionist South in the Union, and who will control that mechanism, the president or Congress?

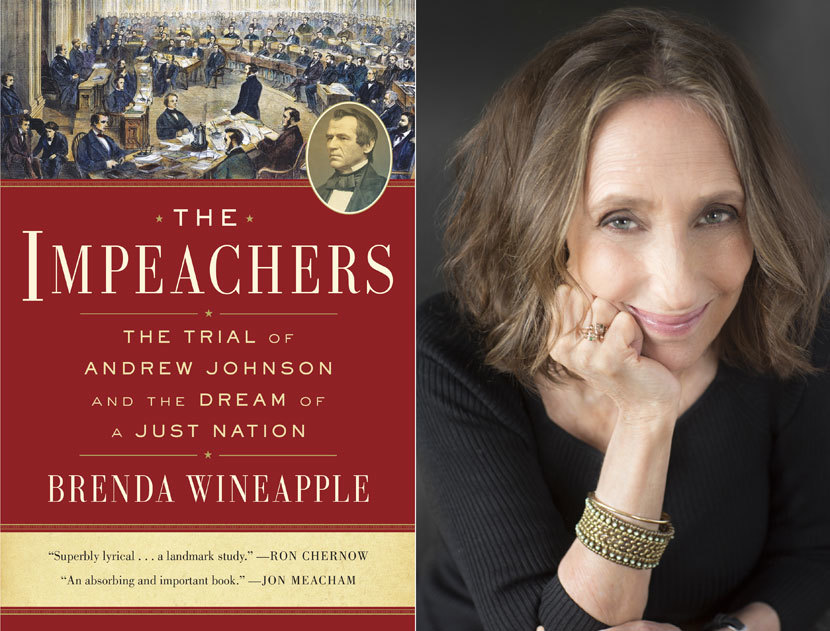

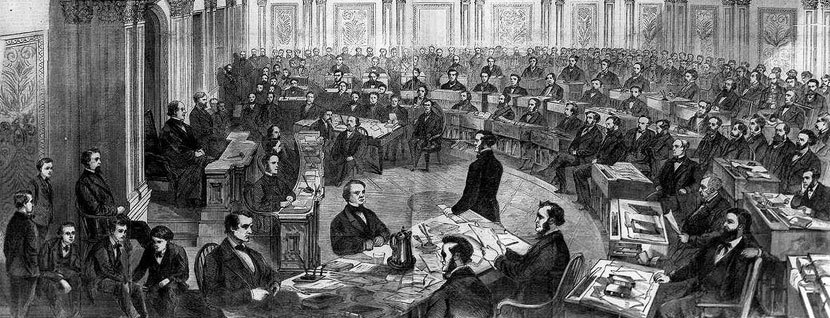

About this last question, Brenda Wineapple shows in her new book The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation, Johnson had no doubt. He would refuse to call Congress back into session after the assassination, preferring to manage Reconstruction from the White House and then, when the calendar finally brought Congress’s return eight months later, to wield the presidential veto as no one had before, thwarting Republican efforts to ensure that former Confederates be punished and that the rights of freed blacks be respected. (Johnson was unabashed in his defense of the United States as “a white man’s country.”) Finally, in February 1868, Congress had had enough, and voted for the first time to impeach a president, a momentous decision that led to one of the most remarkable trials in our nation’s history.

Few authors are as well-equipped to tell this story as well as Wineapple. An acclaimed historian whose books include Ecstatic Nation: Confidence, Crisis, and Compromise, 1848–1877 (a New York Times Notable Book) and White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson (a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award), she is one of our leading experts on nineteenth-century politics and culture. We’re grateful that she could sit down with us for a few questions as her new book goes on sale.

Library of America: Unlike the many instant books dealing with impeachment that have popped up since the election of Donald Trump, The Impeachers is clearly the work of several years’ research and writing. What, in the absence of some special precognition, initially led you to want to tell this story?

Brenda Wineapple: I’d like to think I was prescient, but the fact is that I began researching The Impeachers six years ago—deep into the Obama presidency—when the word “impeachment” didn’t roll off everyone’s tongue as it does today. And yet interestingly, no one seems to know much about the impeachment of Andrew Johnson or the reasons behind it. That’s what initially drew me to this story: Why don’t more people know about the first-ever presidential impeachment, a completely unprecedented event in American history? Why did it fall by the wayside? After all, the impeachment of Andrew Johnson occurred in the aftermath of a brutal war, a presidential assassination, and the struggle not just to end slavery but to create a fair, equal and just republic at last. In that significant context, what did impeachment imply—what did it hope to accomplish, and why was it undertaken at this historical crossroads?

For years, the decision to impeach Johnson seemed to be waved away as a truly preposterous mistake, as some commentators still say. So when I finished writing my previous book, Ecstatic Nation, I realized that I wanted to delve into these issues. And the more I researched Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, the more I came to learn that it represented something truly significant: the attempt to ensure and enshrine equal citizenship for all people and to protect them from anyone who sought to deny those rights.

LOA: Johnson’s trial is one of those rare moments when fundamental constitutional questions become the stuff of daily headlines. What made it so significant? What was at stake?

Wineapple: From the time of the country’s founding, the question of Congressional representation has been a contested issue—and never more so than right after the Civil War, for it wasn’t clear how or when or even if the states in the former Confederacy could or should be allowed back into the Union, all rights restored. Plus, remember that notorious provision in the Constitution that counted slaves as three-fifths of a person in order to inflate the slave states’ apportionment in the House. What now, then, after the Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery, and four million people were free? How would they be counted and represented? Would they be granted voting rights?

In addition, what to do with those states that had seceded from the Union and now wanted a seat at the federal table? These were fundamental constitutional questions about apportionment, and about what “we the people” could mean, going forward. Should “the people” include the former slaves? Women? Though Johnson at first indicated he’d take a hard line against the former rebels, he ignored the civil rights of former slaves, siding with the ex-Confederates while ranting against the Radical Republicans in Congress.

Johnson was soon pardoning former high-ranking Confederates at the rate of about 100 per day. By 1866, he had offered amnesty to more than 7000. He restored their legal and property rights (except in the matter of owning other people) and in some case authorized their return to government posts. And acting unilaterally, Johnson had been proceeding without the advice or consent of Congress, which claimed that he was usurping their rightful role in determining the qualifications for the former states in rebellion entering the Union. He then closed his first year by vetoing the Civil Rights Bill, which would have given the former slaves citizenship. Both houses of Congress swiftly overrode the veto, which inaugurated events that would end with Johnson’s impeachment in 1868.

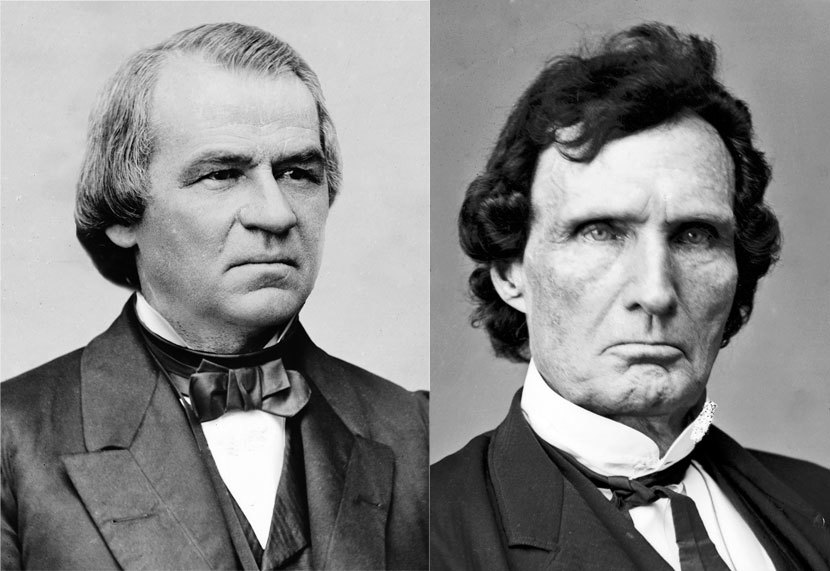

LOA: Like a gripping courtroom drama, The Impeachers is full of vividly-drawn characters, from House managers Benjamin Butler and Thaddeus Stevens, bringing the case against the president in the Senate chamber, to stalwart Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, refusing to be turned out of office, to Johnson himself, becoming increasingly unhinged in the face of these challenges to his authority. To what extent did personality drive the constitutional crisis?

Wineapple: You can’t have ideas, it seems to me, without people articulating or fighting for and against them. Yes, the men and women in and out of Congress are at the heart of a story about the separation of powers, about the aftermath of slavery, about democracy, and about the standards Congress needs to consider when impeaching and removing a sitting president. For they drive the story forward: Andrew Johnson behaved so strangely during his swearing-in as Lincoln’s vice president that cabinet members whispered nervously he must be drunk or crazy, and purportedly Lincoln indicated that he never wanted to speak to Johnson again.

Consider too the brilliant orator Frederick Douglass, who wisely noted that “the impeachment of the President will be a hopeful indication of the triumph of our right to vote,” and the equally brilliant gadfly orator Wendell Phillips, whose calling card read “Peace if possible. Justice at any rate.” There was the powerful if sometimes unlikeable Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, beaten within an inch of his life on the Senate floor for his abolitionist views, who later called Johnson “ignorant, pig-headed and perverse.” There was the wily Secretary of State William Seward, considered the Mephistopheles of the Johnson administration, and his friend William Maxwell Evarts, the lawyer who astutely argued on Johnson’s behalf. Chief Justice Salmon Chase regally presided over the impeachment trial in the Senate while eyeing the White House for himself, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton reminded Congress in vain that women, too, needed the vote for a safe, secure, and lasting reconstruction. Yes, ideas were carried forward by the people whose motives were mixed, people like us who are fallible, who are idealists, who are short-sighted, who are human.

LOA: Thaddeus Stevens emerges as one of the most compelling figures in the book, if not its hero. It was insight to call for an eleventh article of impeachment that turned not on a specific violation of a specific statute, but rather on Johnson’s fundamental unfitness for office, his failure to execute federal laws, and his deprecation of Congress itself. Are there lessons there for lawmakers contemplating the meaning of “high crimes and misdemeanors” today?

Wineapple: Absolutely! Although the Radical Republicans Stevens had been pushing hard for Johnson’s impeachment, Congress was struggling to define the conditions for impeachment, which were as unclear in 1868 as they are now. At first, it was apparent that President Johnson had not committed a specifically criminal act. But that raised a question: should impeachment be understood narrowly, in terms of specific infractions of specific laws, or more broadly, as violations of the public trust and attacks on the state that may not actually break any specific law?

The matter remains debatable today, though it’s worth pointing out that Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 65, notes, “an abuse or violation of some public trust” can be grounds for impeachment. That is, if impeachment is a political process, as Stevens and others argued, and not a legal process, then political crimes, not legal crimes, are grounds for impeachment and must be prosecuted in the Senate.

It seems the issues are still with us in terms of defining “high crimes and misdemeanors.” But I should note that Johnson was finally impeached by the House of Representatives when he seemed to break the law by violating the Tenure of Office Act. He was, however, acquitted in the Senate to a large extent because the narrow interpretation of impeachment held, unlike Bill Clinton, who was acquitted on the basis of a broader interpretation: Clinton committed perjury, but did not violate the public trust.

LOA: “The epoch turns on the negro,” you quote the remarkable Wendell Phillips as saying in 1868, after the effort to impeach Johnson ended in failure and as the problems of Southern resistance and Northern indifference to the struggle for racial justice steadily mounted. “Justice to him saves the nation, ends the strife, and gives us peace; injustice to him prolongs the war.” To what extent are the failures of Reconstruction still with us, as for instance in the current debate over racial reparations?

Wineapple: First of all, I think it’s important to remember that while early historians labeled impeachment as a partisan nightmare hatched by fanatics, this point of view discredited the fair-minded policies, idealism, and in many case the heroism of the Radical Republicans to eradicate, as soon as possible, the misery and injustice that slavery had imposed on an entire people. Also, what’s ignored is that impeachment as enacted in 1868 clearly demonstrated the constitutional system of checks and balances.

But then, as outstanding historians like Henry Louis Gates and Eric Foner or, earlier, W.E.B. Du Bois, have so aptly demonstrated, there was far more implied by what happened than failure and fanaticism. Under the jurisdiction of Congress, which defied Andrew Johnson by passing progressive Reconstruction measures, federal troops in the former Confederacy registered eighty percent of black men to vote, and readmission to the Union depended on ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment. In other words, as I see it, the impeachment of Andrew Johnson was a turning point in our nation’s history, and those people who voted for it and worked to remove Johnson from office were intent on creating a free and fair republic.

We tend to forget that, but when impeachment failed, it did augur the later restoration of the South as the province of white men, who returned to power in a system of inequality that perpetuated racial distrust and violence, that established Jim Crow, that allowed the Ku Klux Klan to flourish, and that largely ignored or derided the Johnson impeachment, its accomplishment and meaning, and the dream, almost realized, of a repaired and just nation.

Brenda Wineapple is the author of several books including Ecstatic Nation, White Heat, and Hawthorne: A Life, winner of the Ambassador Award for Best Biography of 2003, as well as Sister Brother: Gertrude and Leo Stein, and Genêt: A Life of Janet Flanner. An elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Society of American Historians, she regularly contributes to the New York Times Book Review, The New York Review of Books, The Wall Street Journal, and The Nation. For Library of America she has edited two books, John Greenleaf Whittier: Selected Poems and the just released Walt Whitman Speaks: His Final Thoughts on Life, Writing, Spirituality, and the Promise of America.