“One if by land, two if by sea.” The midnight ride of Paul Revere. “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” Washington crossing the Delaware.

Memorialized in popular verse and in iconic paintings, the flashpoint events of the first year-and-a-half of the American War of Independence—Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, Trenton and Princeton—have taken on the shape and force of myth, casting a patriotic glow that can obscure the full complexity of America’s first civil war and the real experience of the soldiers who engaged in the most improbable, seemingly lopsided clash of arms in history.

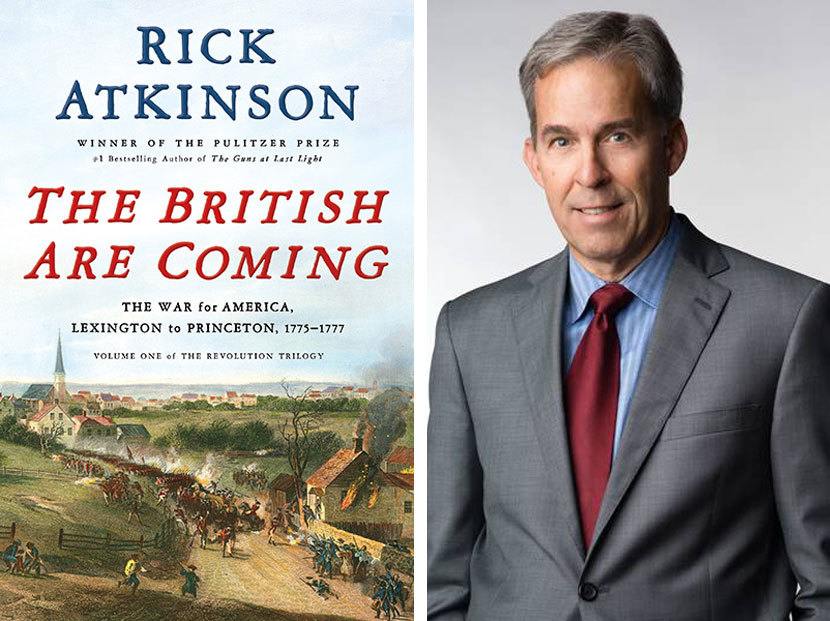

For Pulitzer Prize–winning author Rick Atkinson, it is deep in that experience, in the human dimension of war-fighting, that the true drama of history lies. To tell the story of the American Revolution in The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775–1777, the first of what will be a trilogy, Atkinson deploys the same blend of narrative verve and meticulous attention to detail that distinguished his acclaimed trio of books on World War II in Europe, the Liberation Trilogy. The result, in the estimation of Booklist, is “superb military and diplomatic history and storytelling on a grand scale.”

Atkinson enjoyed a remarkably accomplished career as a reporter and editor at The Washington Post before he turned to writing history. In 2003 he was embedded with the 101st Airborne Division during the invasion of Iraq, an experience he recounted in In the Company of Soldiers, which the New York Times Book Review called “the most intimate, vivid, and well-informed account yet published” about that war. More recently, he has edited the Library of America’s deluxe edition of Cornelius Ryan’s World War II classics The Longest Day and A Bridge Too Far, on sale this month. As The British Are Coming goes on sale this week, Atkinson was kind enough to take some time out to talk with us about the book and what we still have to learn about America’s crucible of war.

Library of America: Few phrases evoke the Revolutionary War as vividly as “the British are coming!” But as you point out, it’s unlikely that Paul Revere ever uttered the famous words attributed to him, in part because they suggest a degree of national differentiation that had yet to emerge in 1775. Is that the essence of the larger story you’re telling here, how the war itself helped to reveal Americans to themselves as a distinct people?

Rick Atkinson: There’s nothing like the Us vs. Them in a war to help resolve certain identity issues, for better or worse. “The British are coming” might have been confusing to people in Middlesex upon hearing it in April 1775, but my guess is that there would have been little ambiguity within a year or two. The schism between the British and the Americans had been developing for more than a century by the time of the Revolution, but gunfire completed the rupture. Benjamin Franklin’s political trajectory is not unusual: over the course of a decade he goes from being deeply loyal—an admirer of the crown and all things British—to being distinctly, proudly, radically American. And that’s despite living in London for most of that period.

LOA: The arc of George Washington’s story also seems telling in this regard. As you note, when the newly minted general of the Continental army traveled to Cambridge to assume command of the militia forces that were besieging Boston, he was not impressed by what he saw, finding New Englanders “an exceeding dirty & nasty people.” Not the kind of thing one expects to hear from the future father of a country. How was Washington able to transcend such prejudices and become a truly national leader?

Atkinson: The five years Washington spent as an officer within a British military organization during the French and Indian war imprinted him with some of the eighteenth century British social distance between superiors and subordinates, officers and enlisted. It took him a while to figure out that there is a mystical bond between leaders and led, and how that bond works in the context of a more egalitarian American culture. When he first became commander-in-chief in July 1775, Washington had difficulty appreciating the great sacrifice being made by the average soldier in leaving his farm, or his shop, and his family to serve the cause.

Washington of course was an immensely wealthy man with overseers and scores of slaves to keep Mount Vernon humming in his absence. It would take the shared experience of hardship, sacrifice, success, failure, and the common pursuit of a common goal to forge unbreakable links between superior and subordinate. At the same time, the army was becoming the indispensable institution for the emerging Republic, led by the indispensable man. His exposure to his countrymen, particularly those from New England and the mid-Atlantic colonies, certainly helps him to think in national terms.

LOA: Many readers might be surprised to learn that one of the Continental Congress’s first major acts after the outbreak of hostilities, at a time when it was barely organized and its resources were scarce, was to launch an ambitious two-pronged invasion of Canada. Why was Canada so important to the American cause? How different might the course of the war have been if the invasion had succeeded?

Atkinson: Yes, in a defensive war supposedly waged for liberty and to secure basic rights, the Americans promptly invaded Canada in an effort to win by force of arms what could not be won by negotiation and blandishment—a fourteenth colony. Among the objectives was to prevent Britain from using Canada as a staging ground for invading New York down the Lake Champlain corridor, cutting off New England from the southern colonies and threatening New York City. Of course that’s exactly what the British tried to do in 1777 after the American invasion failed miserably the previous year.

My guess is that even if rebel forces had succeeded in capturing Fortress Quebec—the only substantive place left in Canada still under British control by November 1776—they wouldn’t have been able to hold it. The British had nimbly mounted a large expedition to expel the invaders from Canada, and then to strike into New York. In some respects it was probably fortunate that the American invasion failed, because the demand for men, munitions, and other supplies to successfully defend, occupy, and administer Canada would have severely taxed Washington’s Continental force to the south.

LOA: Having written about American armies in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, you turn here to the eighteenth. Is there something distinctive about the American way of war that emerges across these vastly different eras?

Atkinson: First, the differences between our modern or contemporary army and the Continental force of the American Revolution are enormous. We put more than 16 million in uniform in World War II; Gen. Washington rarely had more than 20,000 and at times fewer than 3,000. Today’s military force is well-trained, highly educated, physically fit, exceptionally disciplined, and equipped with a lethal, sophisticated arsenal; none of those things applied to Washington’s force, although training improved and his troops were remarkably robust, given the miserable conditions they endured.

We often think of the American way of war in terms of attrition—grinding down an enemy—and firepower, along with logistical excellence and an emphasis on offensive action. But in the Revolution, Washington of necessity mostly plays defense. Logistics are difficult at best, horrible at worst. And in terms of attrition, the Americans are hoping to sap British political will rather than inflicting massive, unsustainable casualties. So while we certainly see some seeds planted in the eighteenth century that will yield that dominant force of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, there’s a great deal that had to happen between then and now.

LOA: The British were fighting what we would now call a counterinsurgency war. How well did their military and political strategies fit together? Are there lessons to be learned today as America continues to fight the longest war in its history?

Atkinson: The shrewdest British generals recognized that success in defeating the American insurgency meant they had to “gain the hearts and subdue the minds of America,” in the words of Maj. Gen. Henry Clinton, who arrived in Boston in 1775 and would later serve as commander-in-chief for four years. King George III and his ministers made several strategic misconceptions, including overestimating the depth and breadth of loyalist support in the colonies, and the extent to which force would cow the rebels. They also underestimated the difficulties in supplying a large army and navy for eight years across 3,000 miles of open ocean in the age of sail.

Sure, there are plenty of lessons that still apply today. Among them: an armed force defending its own turf often has to simply avoid losing the war rather than winning it outright. This gave a substantial edge to Gen. Washington, as it did to our Vietnamese adversaries and as it does to the Taliban. Expeditionary warfare, whether waged across the North Atlantic 240 years ago, or in Iraq a decade ago, is among the most difficult martial enterprises, particularly against a robust insurgency. And hearts and minds remain critical in sustaining any battlefield gains.

Rick Atkinson is the best-selling author of Liberation Trilogy—An Army at Dawn (winner of the Pulitzer Prize for history), The Day of Battle, and The Guns at Last Light—as well as The Long Gray Line, Crusade, and In the Company of Soldiers. He was a staff writer and senior editor at The Washington Post for twenty-five years and his journalism was honored with the George Polk Award and the Pulitzer Prize. For more on the Revolution Trilogy, visit www.revolutiontrilogy.com.