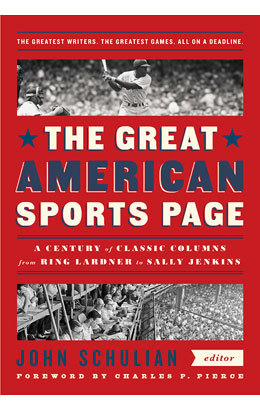

Library of America’s new anthology The Great American Sports Page is a first-of-its-kind celebration of the newspaper scribes who made sportswriting a glorious popular art. Focusing on a particular kind of sportswriting—the column in the daily newspaper—in a way that no other available collection does, the book brings together storied writers of the early- and mid-twentieth century—Ring Lardner, Damon Runyon, Red Smith—and more contemporary figures, some of whom are now well known as television personalities (such as Tony Kornheiser and Bob Ryan) or for their other writings (Mitch Albom). The Great American Sports Page also highlights the contributions of pioneering female journalists (Diane K. Shah, Jane Leavy, and Sally Jenkins) who, in more recent decades, broke into what had been an exclusively male bastion.

The book’s editor is John Schulian, formerly a sports columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times and Philadelphia Daily News and a recipient of the PEN/ESPN Lifetime Achievement Award for Literary Sports Writing. He edited the Library of America anthologies Football: Great Writing about the National Sport and, with George Kimball, At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing and is the author, most recently, of the novel A Better Goodbye.

Below, Schulian discusses some of the hard choices he had to make in compiling the anthology, what the form has meant to so many readers over the past hundred years, and the challenges it faces in the twenty-first century.

Library of America: The Great American Sports Page is the first anthology devoted to newspaper sports writing, columns in particular. How did you decide to take this approach?

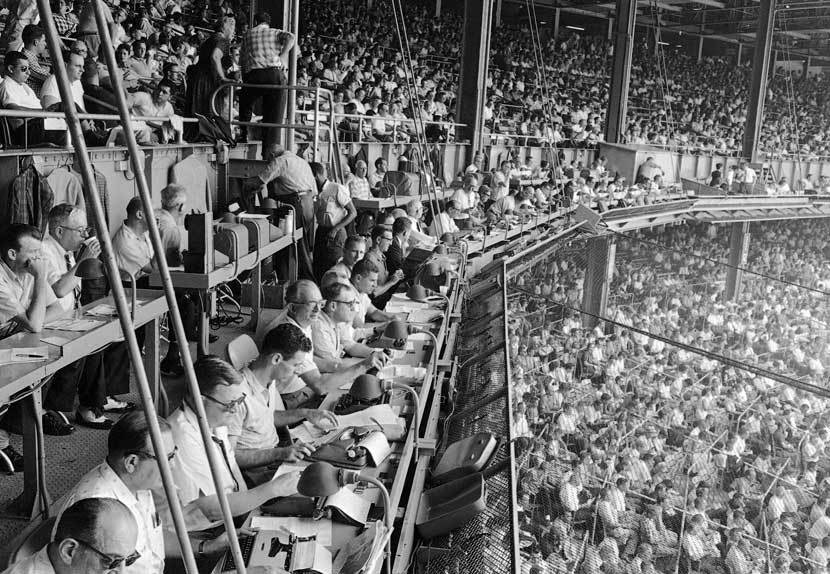

John Schulian: It was the logical thing to do. I’m a newspaper guy. I spent sixteen years in the business, nearly ten of them as a sports columnist. Even when I walked away from my sixth and last paper to go to work in Hollywood, people remembered me for what I had done in the press box if they remembered me at all.

In addition to giving me an identity, newspapers were where I learned to write. Some of my very best teachers were the wordsmiths who stared down ferocious newspaper deadlines every day and wrote beautiful, memorable prose that deserved a fate better the bottom of a bird cage. I learned by studying what Jim Murray and Larry Merchant could do in the 800 to 1,000 words that most columns ran in the 1960s. Then it was up to me to track down the masters they had learned from, sports writing legends like Red Smith, Jimmy Cannon, and W. C. Heinz. The best of their work had been collected in anthologies—Red’s Out of the Red, for example, and Cannon’s Nobody Asked Me—so that’s where the idea for The Great American Sports Page came about. The big difference was, I wasn’t devoting the book to the work of just one columnist. I wanted to squeeze as many of them as I could into 400 or so pages. I didn’t realize no one had ever done it before. I just thought I was concocting the equivalent of a once-in-a-lifetime sports section. Where else are you going to find Damon Runyon, Tom Boswell, and Joe Posnanski in the same line-up?

LOA: You attach a great deal of importance to sports columnists. One might even say you see them as the rock on which a sports section is built. How do you explain the weight they carried?

Schulian: As newspaper sports sections grew and improved, columnists defined them in terms of voice and personality. If a paper had a great or charismatic columnist, he—women didn’t enter the picture until late in the twentieth century—attracted not only readers but writers who wanted to work with him and maybe even write like him. Look at Red Smith, whose elegant, slyly amusing columns were perfect for the Rockefeller Republican readership of the New York Herald Tribune. All around him were beat writers and feature writers who put the same premium on literacy that Red did. The result may have been the best sports section this country has ever seen.

Obviously, not every city had a Jimmy Cannon or a Red Smith making magic out of ball games and prize fights. Sometimes the local sports columnist was a shill for the old home team, or a hack rewriting out-of-town scribes, or simply the editor’s drinking buddy. I can tell you for a fact that inspired prose was in short supply on the sports pages I read as a kid in Salt Lake City. But every now and then, great sports writing found its way into the papers in the form of nationally syndicated columns by Smith or Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times, who was a one-man laugh factory. As gifted and inventive as these giants were, they had needed role models too, pioneering wordsmiths like Ring Lardner, Damon Runyon, and Heywood Broun who make up the first part of The Great American Sports Page. We see them as columnists and sometimes in an earlier role as reporters whose stories gave the sports page a pulse and whose feature stories brought athletes into sharp focus as human beings. There’s Runyon on an unlikely home run by Casey Stengel, Bob Ryan on the Boston Celtics as rulers of all they can see, Tom Boswell on a pennant race that came down to the season’s last day. All three went on to become columnists.

LOA: What makes the column form so distinctive?

Schulian: They say styles make great prize fights. That’s why Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier gave us such epic battles. Facing each other, they were nuclear; against certain other boxers—Ali versus Ken Norton or Frazier versus George Foreman—they were uncomfortably mortal. You can say that styles make great sports columnists too. The fight is between the writer and the English language.

What the columnist’s job called for was someone comfortable in his own skin. Leigh Montville charmed Boston Globe readers with humor that floated between belly laughs and bewilderment. Wells Twombly had a florid, often bombastic style that worked to perfection in the San Francisco Examiner. Then there is Sally Jenkins of the Washington Post, whose bloodlines as the wickedly hilarious Dan Jenkins’s daughter suggested she would specialize in jokes. Instead, though she is not without a funny bone, she takes on the toughest issues sports can offer, and woe to the scoundrel who tries to put something over on her.

The columnist’s voice should be consistent but not inflexible. The voice, after all, is what lures readers into the tent. They want the columnist’s attitude, his take on whatever he’s writing about, but readers want to be surprised too. They want to see the columnist swim against the tide or paint a hero or villain as different than what his image says he is. The columnist’s stock in trade, of course, is opinions. Indeed, more than any other time since sports writers left the ivory tower of the press box and entered dressing rooms to find out what really happened, the sports page is awash in opinions. While opinions are nice—I have some myself—they can be wearying in their current abundance. Worse, public demand for them squeezes out the fun that columnists should be allowed to have when writing about fun and games.

LOA: Your selections in The Great American Sports Page span nearly a hundred years. How has the writing evolved over all that time?

Schulian: In the early twentieth century, baseball was the heart and soul of American sports writing, and the cradle of baseball writing was Chicago, where the knights of the keyboard, Ring Lardner foremost among them, developed a style that was as full of fun as it was facts. Once they had taken care of the score and the day’s heroes, they seemed free to wander off in any direction that captured their fancy. There’s a Lardner piece in the book, for example, that salutes the retiring Mordecai (Three Fingers) Brown by recalling what a soft touch he was for a loan and how quick he was to pick up the check for dinner.

Grantland Rice was the next big thing in sports writing, a courtly Southern gentleman who slopped adjectives on his prose with the same tireless passion as a house painter who gets paid by the bucket. It didn’t matter whether Granny, as his friends called him, was covering a high school football game or his legendary Four Horsemen from Notre Dame—everything was the end of the world. He was the Big Kahuna of the Gee Whiz school of sports writing. Judged by today’s standards, he seems over the top, even borderline ridiculous, but you have to remember he was writing before TV and, in some cases, before widespread radio coverage. Readers loved him. He was huge in syndication. But these lords of the press box refused to go down to the dugout or clubhouse and interview the people they were writing about. In the early 1930s Frank Graham, the New York Sun’s newly-minted sports columnist, saw how inherently silly this unwritten policy was, and the next thing anyone knew, he was listening to athletes talking to each other, then rushing back to his typewriter without having taken a note and recreating the conversation.

It didn’t take long for sports writers to realize that athletes were just people too, and that they should be portrayed as such whether they were bright young men (and women) or mouth-breathing dullards, clubhouse comedians or crackers who still thought the back of the bus should count for something. The mid-Fifties and Sixties were a fine time to be a sports columnist who had a flair for psychoanalysis of pitchers who had just lost a game by giving up a home run. Two hard-charging sports editors—Larry Merchant of the Philadelphia Daily News and Jack Mann of Long Island’s Newsday—set the tone by preaching iconoclasm, irreverence, and social consciousness.

Those of us who came along in the Seventies and Eighties capitalized on what these crusaders had done. They were the high tide that raised sports writing. First-rate sports sections began to emerge all around the country, in Boston, New York, Philly and Washington on the East Coast and L.A. on the West Coast, Chicago and Detroit on opposite sides of Lake Michigan, and Miami, Atlanta and Dallas across the South. None were ever perfect, but, damn, there was some good reading out there, and it was being done by more than the usual suspects. Women and African Americans were bringing new dimensions to sports writing with insights and life experiences that had previously been missing from the genre.

LOA: Do you have any personal favorites in the collection? We’re especially interested in hearing about any of the “deadline artist” variety (i.e., writers trying to capture the essence of an event in a very short time).

Schulian: To me, this book is partly a reunion of old friends, people I worked with or competed against, laughed and talked music and movies with, and probably dragged to eat at a greasy spoon where the smart money said we’d never make it out alive. It pained me more than you might imagine when I couldn’t include everybody whose writing I admire. But my primary goal was to show how memorable work could be found all around the country. I knew that scribes from the Boston–Washington corridor would be well-represented; I just wanted to make sure Seattle and New Orleans were too.

When I began the selection process, I definitely had certain pieces in mind. I knew, for instance, that the book would be a sham if it didn’t include Bill Heinz’s 1949 classic “Death of a Racehorse” simply because it is the greatest newspaper sports column ever. Devout readers of the sports page would recognize the bylines of Red Smith, Jimmy Cannon, and Jim Murray, so I felt obligated to shine a light on writers just as worthy but less well-known: Emmett Watson on a boxer at the end of the road, Jim Klobuchar flexing his wit when the subject was pro football, Diane K. Shah beating a notoriously uncommunicative pitcher at his own game. And always I wanted to share the joy of reading Larry Merchant as he waited for baseball’s opening day with the poet Marianne Moore and Jerry Izenberg as he counted an old rodeo rider’s broken bones.

What each of these pieces represents is the writer’s search for an idea. Red Smith and the brilliant horse racing columnist Joe Palmer had a prayer they uttered when it was time to work: “Give us this day our daily plinth.” Plinth is the Greek word for the base of a building or statue. The plinth that Smith and Palmer sought was something worth writing about. When they had it and had done the necessary footwork, interviewing and cogitating, then it was time to write. Palmer was a blur, capable of turning out an entire column in the time it took Smith to bleed out his opening paragraph. Not that Red couldn’t write in haste when his deadline called for it, but he preferred to massage each sentence until it was as close to poetry as he could bring it.

Merchant was equally painstaking. Bill Nack, too. Nack, a star columnist at Newsday before he became a Sports Illustrated legend, loved to tell the story of the night the press box in Detroit’s old Tiger Stadium closed before he could finish writing. He wandered through the shuttered ballpark until he found a hot dog stand with a single light burning overhead and went back to work as feral cats chased down rats in the darkness surrounding him.

But newspapers are, first and foremost, a sprinter’s business. Major sports events happen primarily at night, or should I say they abide by TV’s clock, seeing as how TV pays scandalous amounts of money to show them. But even in the days when newspapers were king, sports writers had a daily race to run when their deadlines bore down on them. Success and failure were measured in minutes, and not very many of them at that. Read Dick Young’s account of a Dodgers game during the 1946 pennant race and you’ll see how vivid and inventive a writer can be when he feels the hot poker of a deadline. Read Robert Lipsyte’s story of the then Cassius Clay’s upset win over baleful Sonny Liston and you’ll marvel at how much action, history, perspective, astonishment, and character he could jam into the fever dream his piece became.

The champion of all the deadline artists in the book, however, is Richard Hoffer, who made his reputation at the L.A. Times by writing boxing, yet he soared to new heights with his under-the-gun masterpiece about gymnast Mary Lou Retton winning a gold medal at the 1984 Summer Olympics. Everything you’d want in an essay written with the luxury of time—imagery, turns of phrase, personality, emotion, quotes born of thoughtful interviewing—is right where you want it, all tied up with a bow of elegant prose. And Hoffer did it in forty minutes. I don’t know what to say except wow.

LOA: The book showcases the work of the women sportswriters Diane K. Shah, Jane Leavy, and Sally Jenkins. What had to change in order for these women to break through?

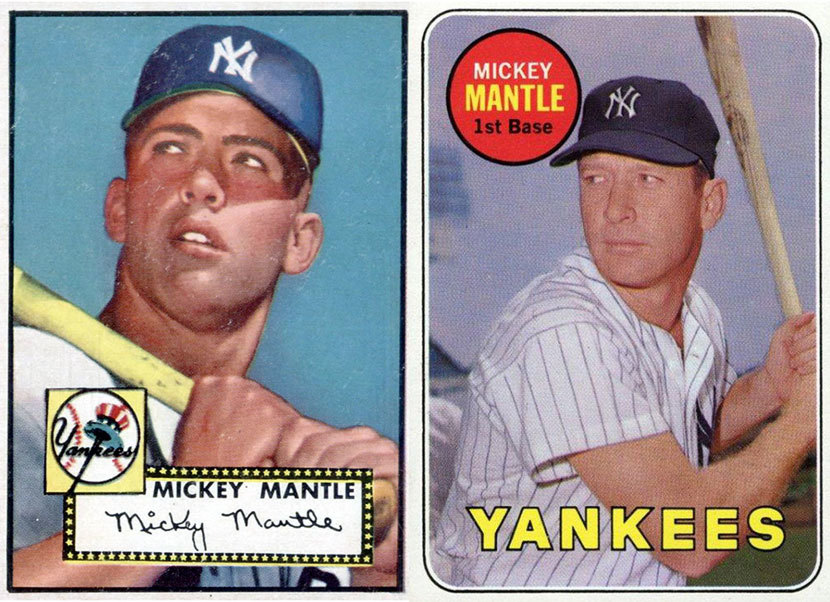

Schulian: First, men had to get over themselves. Women could actually understand pitching strategy and exotic football defenses. They didn’t turn and run every time some bruiser or furnace-faced coach blew up at them. But they did have the ability to take interviews where they might not have gone if a male writer was asking the questions. When that happened, women unearthed the kind of surprises that make sports stories special, the way Jane Leavy’s profile of Mickey Mantle at sundown is special.

Shah, Leavy, and Jenkins are the spiritual descendants of Mary Garber, who is in the book only between the lines. Garber was the country’s first full-time woman sports writer, entering the business because all the men had gone off to fight World War II and spending more than forty years covering every game that came her way at the Winston-Salem (N.C.) Journal.

The other key figure in all this is Melissa Ludtke, the Sports Illustrated reporter who filed the lawsuit that opened baseball clubhouses to women journalists.

LOA: Boxing aficionados, as we know, can lay claim to a particularly proud literary tradition. Is it fair to claim that one or two sports have inspired an outsized amount of the best writing?

Schulian: You bet it’s fair. Baseball and boxing cornered the market on coverage for one simple reason: they were the best sports to write about. The proof is in the sports pages from the turn of the twentieth century until the late Sixties and early Seventies, when the NFL began to seize control of just about anything it pleased. The players could be bright, funny and insightful, but that didn’t always meet management’s approval. Too many head coaches took their cues from Patton (the general or the movie) and delighted in telling reporters they wouldn’t know anything about the game just ended until they looked at film of it. Worse yet, they weren’t lying. No wonder the NFL with few exceptions—the Super Bowl shuffling 1985 Chicago Bears, for one—seemed a joyless enterprise for anybody with the urge to tell stories and laugh it up with rowdy characters.

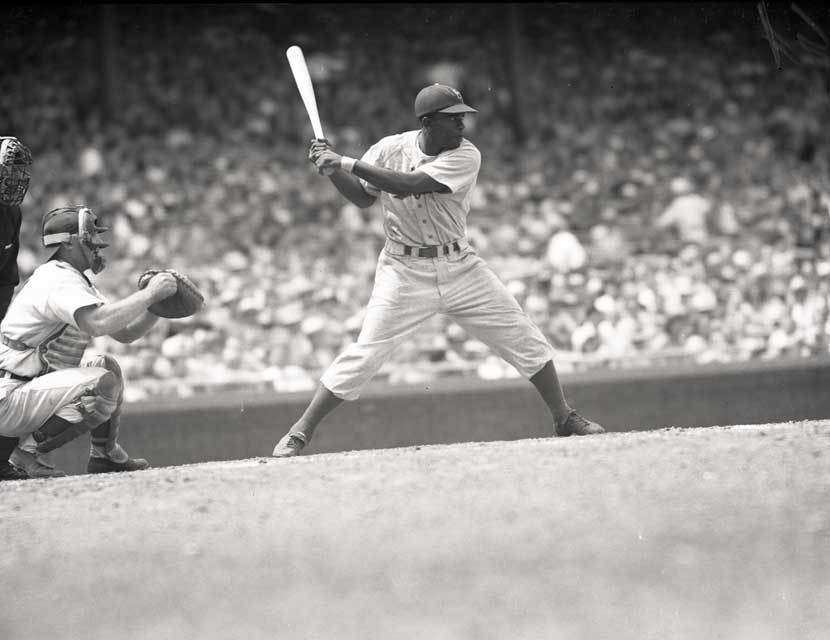

Baseball, on the other hand, was a storyteller’s sport, a tobacco-stained, profanity-laced subculture populated by ballplayers nicknamed Dizzy and Mudcat and managers who could make their tales of minor league life sound as though Mark Twain had written them. Any writer who couldn’t find something to turn into a column or feature had obviously been lobotomized—and the game hadn’t started yet. Once the first pitch was thrown, the real magic—the magic of Babe Ruth and Willie Mays and all of baseball’s other greatest players—was on display, and it could move a columnist to the artistry Red Smith achieved when he wrote about Bobby Thomson’s historic home run against the Dodgers.

It’s entirely possible, however, that boxing was an even better sport for writers. In gut-bucket gyms, ticky-tack arenas, and the Las Vegas hotels that used to put on championship fights, you could find characters straight out of film noir. Scheming promoters, noble corner men and boxers with rap sheets that stretched all the way to Poughkeepsie seemed to be waiting for writers to walk in the door. I stumbled upon this treasure trove when boxing was enjoying what may have been its last golden age. Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier were wrapping up their unforgettable trilogy just as brilliant young fighters like Sugar Ray Leonard, Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Roberto Duran, and Tommy Hearns came along to capture the spotlight. It was an ugly, brutal, life-shortening sport, and yet it could move sports writers to poetry even if they were appalled by their subject. And their readers gobbled up every word that was written about it.

Now that day is gone. Even world champion boxers seem anonymous. So, to be honest, do baseball’s very best players. Mixed martial arts—cage fighting, if you prefer—satisfies the blood lust of younger audiences. Baseball gets rightfully pilloried for being too slow to satisfy a world overrun by the need for instant gratification. Basketball seems far better suited for these times. No wonder the L.A. Times has a platoon of first-rate writers covering the NBA. But football remains the perfect game for the twenty-first century even as the issues of concussions and long-term damage soil its image. The games are fast and violent, a mixture of chess and demolition derby, and constant replays only amp up TV coverage. But what of the poor scribe? I suppose he or she abides, like the Dude in The Big Lebowski. At least he knows readers are interested in what he’s writing about.

LOA: What did the daily sports page offer in its prime that we no longer have in our digital world?

Schulian: In this tweeting and blogging world, the constant demand for information has all but eradicated a type of sports column that I loved as both reader and writer. I’m talking about the column that comes into existence for no greater purpose than to entertain. It could be a character sketch or a scene piece. It might be based on idea that’s been bouncing around inside your head for days or weeks, or maybe the columnist, desperate for a subject, plucks the idea out of the air.

But there was no rule that said you had to keep this kind of column light and frothy. You could get personal too, and I did, never more so than when I was entering a particularly turbulent stretch in my life. I was using my column to work things out as best I could and readers responded with a warmth and kindness I hadn’t expected. When I think of that experience after all these years, I see something that’s rarely found in the digital world. It’s called soul.