May 31, 2019, marks the 200th birthday of Walt Whitman, the poet whose “barbaric yawp” burst forth in 1855, with the self-published first edition of Leaves of Grass, and has resonated around the world ever since.

Library of America’s contribution to the Whitman bicentennial celebrations is Walt Whitman Speaks, a selection of the poet’s thoughts taken from the wide-ranging conversations he had late in life at his home in Camden, New Jersey, with the young journalist Horace Traubel. Traubel’s faithful transcriptions of those talks eventually filled a sprawling nine volumes; the new LOA edition, edited by Brenda Wineapple, distills this shelf-full of books into a concentrated essence of Whitman.

Below, as an accompaniment to Walt Whitman Speaks, we offer a look at some of the New Jersey locations that formed a backdrop to Whitman’s later years. Our guide is the author and photographer John Suiter, who shot the area on assignment back in the early 1990s; readers of this blog may remember that Suiter previously provided Library of America with visual tours of Walden Pond and Robert Lowell’s Boston. Based in Chicago, Suiter is the author and photographer of Poets on the Peaks: Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen & Jack Kerouac in the North Cascades (Counterpoint, 2002). He is currently writing a biography of Gary Snyder.

All photos: © John Suiter. All rights reserved.

By John Suiter

Whitman suffered a “paralytic stroke” in January 1873. He was not yet fifty-four. Four months later, his mother died—“the saddest loss and sorrow of my life,” he wrote in Specimen Days, his 1882 volume of prose reminiscences. Depressed and physically weak, he gave up his government job in Washington, D.C. (he worked for the Department of the Interior), and moved in with his brother George in Camden in June of 1873.

As he summarizes the period in Specimen Days:

In February ’73 I was stricken down by paralysis, gave up my desk, and migrated to Camden, New Jersey, where I lived during ’74 and ’75, quite unwell—but after that began to grow better; commenc’d going for weeks at a time, even for months, down in the country to a charmingly recluse and rural spot along Timber creek. . . . Domicl’d at the farm-house of my friends, the Staffords, near by, I lived half the time along this creek and its adjacent fields and lanes. And it is to my life here that I, perhaps, owe partial recovery (a sort of second wind, or semi-renewal of the lease of life) from the prostration of 1874–’75.

What Whitman called Timber Creek is the North Branch of Big Timber Creek, a meandering watercourse with many tributary springs and ponds that flows generally northwest through Camden County, past places called Chews Landing, Black Horse Pike, Runnemede, and Bellmawr and enters the broad Delaware River across from the Philadelphia Navy Yard, a mile and a half downstream of the Walt Whitman Bridge. The stretches of Timber Creek that Whitman frequented are called Crystal Springs and Laurel Lake.

In 1876 Whitman met eighteen-year-old Harry Stafford, a “printer’s devil” at the Camden press where Walt’s book Two Rivulets was being laid out. Whitman took an interest in young Harry, began advising and mentoring him, and, after a time, Harry brought Walt to meet his parents at their farm in Laurel Springs (then called “White Horse”). The Staffords loved Walt, and invited him to visit as often as he liked. No one in the Stafford family objected to Walt and Harry’s obviously physical relationship. They liked to whoop and wrestle in the yard “like a couple of boys,” giddily pinning each other to the ground. Harry’s mother, in later years, recalled Whitman as “the best man I ever knew.”

His love affair with Harry Stafford, which would last for the next eight years until Harry got married, was Whitman’s last long-term relationship. He addressed his much younger partner (they were forty years apart) in letters as “my darling boy,” and in public introduced him as “my adopted son,” “my nephew,” or simply, “my young man.”

“If I had not known you—if it hadn’t been for you and our friendship & my going down there summers to the creek with you . . . I believe I should not be a living man today—I think & remember these things & they comfort me—& you, my darling boy, are the central figure of them all.”

Crystal Springs, which is still quite a secluded place, is a bit more than a quarter-mile from the old Stafford family house. Here, as part of his self-rehab from his stroke, Whitman stripped down and did pull-ups from the low branches of favorite hickories and oaks. He also used to do regular naked sun- and mud-baths along the creek, whipping himself clean with willow wands and laurel until his skin glowed from the increased circulation.

I came down here for the daily and simple exercise I am fond of—to pull on that young hickory sapling out there—to sway and yield to its tough-limber upright stem—haply to get into my old sinews some of its elastic fibre and clear sap. I stand on the turf and take these health-pulls moderately and at intervals for nearly an hour, inhaling great draughts of fresh air. (Specimen Days)

At times Whitman would get rough with some of his trees. He might actually grapple with a ten or twelve-footer, as though it were some strapping young fellow, or certainly a fellow sentient being with whom he could exchange energies:

Exercising arms, chest, my whole body, by a tough young oak sapling thick as my wrist, twelve feet high—pulling and pushing, inspiring the good air. After I wrestle with the tree a while, I can feel its young sap and virtue welling up out of the ground and tingling through me from crown to toe, like health’s wine . . .

At other spots I have selected strong and limber boughs of beech or holly, in easy-reaching distance, for my natural gymnasia, for arms, chest, trunk-muscles. I can soon feel the sap and sinew rising through me, like mercury to heat. I hold on boughs or slender trees caressingly there in the sun and shade, wrestle with their innocent stalwartness—and know the virtue thereof passes from them into me. Or maybe we interchange—maybe the trees are more aware of it all than I ever thought. (Specimen Days)

Timber Creek has been called “Whitman’s Walden Pond”—a comparison first hinted at by Whitman himself, who often read Thoreau along this stream. But Walden is a work of youth, presided over by the morning star and a feeling of “more day to dawn.” It was lived when Thoreau was in his late twenties, and published when he was still only thirty-seven. Whitman first came to Timber Creek—hobbled to it, by his own description—when he was fifty-seven. Specimen Days, much of it written at creekside, and published when Whitman was sixty-three, is clearly a work of what Jung would call “the second half of life.” Thoreau never had a “second half”; he died when he was forty-five. (In Walt Whitman Speaks, Whitman remarks, “his [Thoreau’s] dying does not seem to have hurt him a bit: every year has added to his fame.”)

Whitman died in this room on the second floor of his Mickle Street home on the night of March 26, 1892, age seventy-two. The immediate cause of death was pulmonary emphysema, but three years before, in June 1888, he’d had a series of strokes, even more debilitating than the one in 1873. Whitman was now sixty-nine. The strokes left him mostly bedridden and “imprisoned” in this sick room for his remaining life.

The above is how Whitman’s room looked in July 1990. On the wall over his chest-of-drawers hangs a print of one of the best-known photographic portraits of Whitman—made by Brooklyn photographer G. Frank Pearsall around 1870.

The bronze bust of Whitman in the left foreground was not done from life. It was sculpted by Louis Mayer (1869–1969), a Wisconsin artist who had a studio on 42nd Street in Manhattan, around 1913. The bust is undated but was donated by Mayer to the Whitman House in 1948.

Whitman’s life in Camden was a history of paralytic strokes, partial recovery, inevitable decline, tomb-building, and death—not exactly the landscape of the freewheeling singer of the Body Electric that most Whitman fans love. For all of that, Whitman was prolific in Camden. There he wrote much of Specimen Days, November Boughs, and Goodbye, My Fancy, and oversaw the publication of his final Ninth Edition of Leaves of Grass. At Mickle Street he was sculpted, painted, photographed, interviewed, and biographied, and visited by a continuous stream of illustrious visitors from around the world, who made the trip to Camden just to see him.

As Justin Kaplan notes in his 1980 biography Walt Whitman: A Life, concerning Whitman in Camden: “Almost alone among the major American writers, he achieved in his last years radiance, serenity, and generosity of spirit. . . . From there he looked back on the cities of his youth—New York, Brooklyn, New Orleans, Washington. ‘They are my cities of romance. They are cities of things begun—this is the city of things finished.’ An old man who never married and had no heart’s companion now except his books, he rode contentedly at anchor on the waters of the past.”

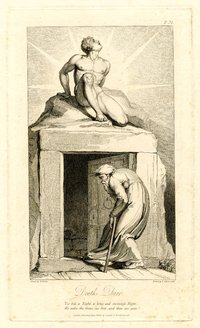

Whitman’s tomb—which he designed himself and closely oversaw the construction of—is at the eastern edge of Harleigh Cemetery, on the banks of the Cooper River, two miles from Mickle Street. As Kaplan notes, Whitman, who as a boy had been profoundly saddened and shamed to see the neglected graves of his forebears on Long Island, wanted his own tomb to be “a plain massive stone temple” built into a hillock. At Mickle Street he drew the plans for it based on William Blake’s 1808 etching “Death’s Door” (inset, right).

The irony is obvious, of course. Anyone who has ever exulted in the brash young Whitman of Leaves of Grass may recall his saying:

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

—“Song of Myself” (52)

But as Kaplan writes, “the old Whitman demanded more pharaonic arrangements. He built himself a burial house that was stark, elemental and secure. . . . An earthquake and an angel of the Lord would have to roll back the stone from his door.”

Excerpt from Whitman’s letter to Harry Stafford is from Edwin Haviland Miller ed., The Correspondence, Vol. III in the New York University Press edition of The Collected Writings of Walt Whitman, as quoted in Walt Whitman: A Life, by Justin Kaplan.