Long an overlooked and misunderstood period of American history, Reconstruction has been the subject of much attention of late, both in scholarship and in our popular and political culture, with events like Charlottesville reigniting debates over how the past should be remembered.

For twelve tumultuous years, from 1865 to 1877, Congressional Republicans attempted to usher in a second American revolution, one that would finally fulfill the promise of the first by rebuilding the fractured union as a biracial democracy. Met by intransigence in the South and increasing indifference in the North, their efforts failed, and what followed instead was a long and brutal period of reaction. From the ruins of the slave system, southern Democrats built a new regime, a complex of laws and cultural codes that became known as Jim Crow, which would persist for nearly a century and whose legacy remains very much alive today.

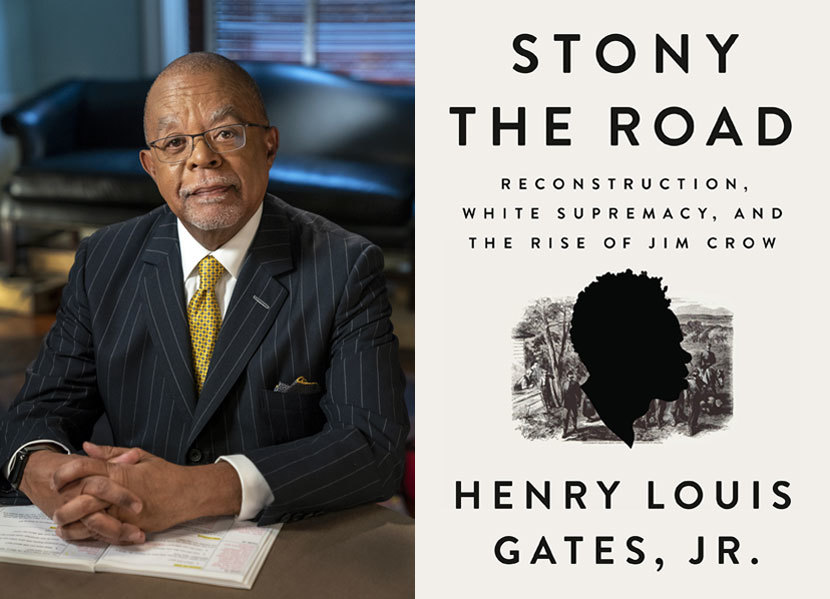

As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., shows in his new book Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow, the superstructure of Jim Crow rested on a foundation of dehumanizing racialist ideology that was pervasive (by no means limited to the South), violent, and unabashed. While relating this grim story, Gates also celebrates the real achievements of Reconstruction, what W.E.B. Du Bois called “a brief moment in the sun” for African Americans. However short, the period was crucial not just for the severe backlash it engendered, but for the inspiration it provided for the New Negro Movement of the early twentieth century.

Gates is perhaps the nation’s best-known scholar, seen regularly by millions of viewers of Finding Your Roots and his award-winning documentaries on PBS. Director of Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, he is a prolific author and editor, including for Library of America, of which he has been a trustee for more than twenty years. As Stony the Road goes on sale and his latest documentary, Reconstruction: America After the Civil War, premieres on PBS tonight, Professor Gates was kind enough to take some time out for a few questions.

Library of America: As you describe in the preface to Stony the Road, Reconstruction has been a subject of abiding interest for you since you were an undergraduate at Yale. What is it that you most hope readers will understand about this period after reading your book and seeing your film?

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.: The story of Reconstruction and its overthrow after only a dozen years shatters all notions that history is a straight line drawn inexorably toward progress, and in that shattering there is a lesson for us all: vigilance. As we grapple with another rollback following the eight-year presidency of the first black man to hold the office, we cannot escape our own civic duties to preserve the gains we’ve earned by exercising our vote, holding those in power to account, defending our democratic institutions, and lifting each other up when the will of others becomes sapped and fears and anxieties crowd in.

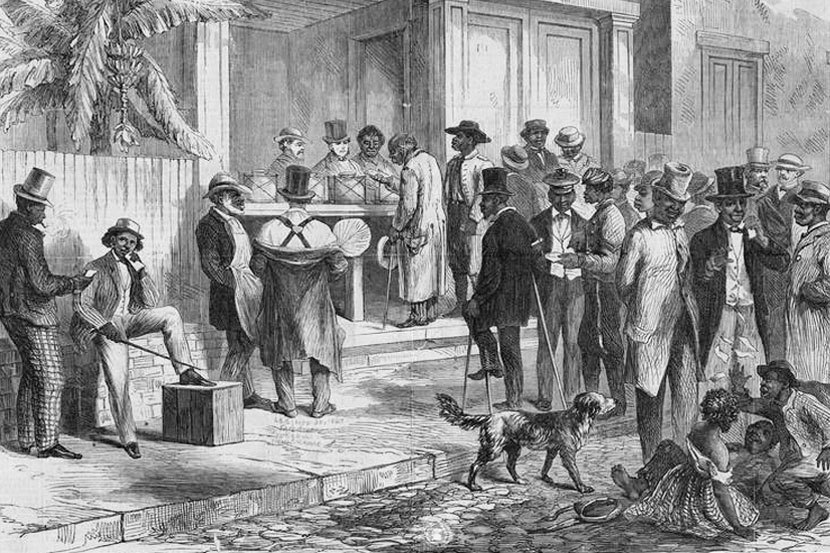

Without a doubt, there is an added urgency to spreading the word about Reconstruction today. In these turbulent times, without wrestling with this chapter in our past, we cannot make sense of why we needed a civil rights movement a hundred years after the Civil War, we cannot gird ourselves for the hard work that democracy requires, and we cannot honor our ancestors who sacrificed all in war and peace to push for the rights of freedom and equal citizenship long denied them, even after the tsunami of white supremacist resistance overwhelmed Reconstruction and the federal government retreated from its responsibilities. Long before the Freedom Summer of 1964, there was the first “freedom summer” of 1867, when, under the watch of federal troops in the former Confederacy, 80 percent of black men registered to vote, paving the way for over 2,000 black officeholders at every level of government before Reconstruction was toppled. This book and series are for them.

LOA: As you suggest, from voting rights to birthright citizenship, much of the legal legacy of Reconstruction—a legacy that itself wasn’t fully realized until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s—is under assault today, and white supremacist ideology has emerged once more into the foreground of our politics. How might an attention to the history of Reconstruction and Redemption help us understand this recrudescence?

Gates: So often in our history, we see revolutions incite counter-revolutions in a series of often violent pushes and push-backs that complicate the meaning of freedom and equal rights. Reconstruction and Jim Crow are the perfect example of that. The political power ex-slaves in the South claimed within a few years of the surrender at Appomattox, from voting to drafting new state constitutions to representing their states in Congress, provoked a violent backlash that would not rest until white southern Democrats “redeemed” every last former Confederate state government through bloodshed, intimidation, and fraud.

But this wasn’t just about turning the clock back or winning what my friend Bryan Stevenson calls the narrative of the Civil War through Lost Cause mythology and practices. The white supremacist counter-revolution against Reconstruction was about creating a new kind of state based on a form of racial apartheid that would make the color line the ultimate demarcation between an American Dream available to white citizens and various forms of neo-slavery for black citizens. Once that line was drawn in the 1890s and early 1900s, and blessed by the United States Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, it condemned generations to second-class citizenship, even as those citizens used every tool left available to them to defy the stereotypes and expose the horrors and injustices deployed to underwrite their disfranchisement.

LOA: You survey, often in chilling detail, the multifaceted manifestations of white supremacy in American life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, from picture postcards and plantation literature to phrenology and eugenics. As someone who has spent a lifetime in the academy, do you find the role that the nation’s premier institutions of higher learning played in perpetuating racist theories particularly disturbing?

Gates: It’s impossible not to be deeply disturbed by the role that America’s most elite universities played in advancing scientific racism in the late nineteenth century (that includes my own Harvard) and in framing Reconstruction as a chaotic failure that demanded the re-establishment of “law and order” by such lawless white supremacist groups as the Ku Klux Klan.

At the same time, I cannot help but see the poetic justice in the fact that Columbia University, which, more than any other school, promulgated this racist view of Reconstruction in the early twentieth century in what was known as “the Dunning School,” is now the home of Eric Foner, the greatest historian of my generation, who, building on the work of W.E.B. Du Bois in the 1930s, has permanently revised our understanding of Reconstruction as a noble, if too short-lived, experiment in interracial democracy that reconstituted the Union on the basis of freedom and equal citizenship rights, while creating a space for black institution-building and public education that remains vital to our country today. It is the “Du Bois–Foner School” that has prevailed in the long run, and will endure.

LOA: The post–Civil War story you tell is in one sense the story of war by another means, what you call “a war of representation,” as white Americans sought to portray black Americans as less than human to justify their return to a state of de facto slavery. To illustrate this you bookend each chapter in Stony the Road with portfolios gathering some truly disturbing racist imagery. Why was it so important to include this material in the book?

Gates: The visual record of anti-black racism in the period I cover is so overwhelming—is such an avalanche—that I wanted to find a way to let it speak for itself in an unmediated way, so that readers today can get a sense of what it must’ve been like to be alive in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when one was bombarded on a daily basis with postcards, advertisements, trading cards, you name it, that debased black people in a series of brutalizing “Sambo” stereotypes that called out for a response.

What’s remarkable about the period is that black people did respond, seizing on new technologies, including photography and film, in order to present to the public—and to themselves—a more authentic portrait of black faces and lives, while others worked toward envisioning and realizing a “New Negro” that would help usher America and the world into a more modern, cosmopolitan, and enlightened age.

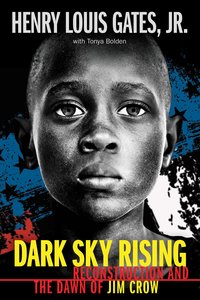

LOA: In conjunction with Stony the Road you have also just published Dark Sky Rising: Reconstruction and the Dawn of Jim Crow, a book for young readers coauthored with Tonya Bolden. What was the biggest challenge for you in trying to make this story accessible for young people?

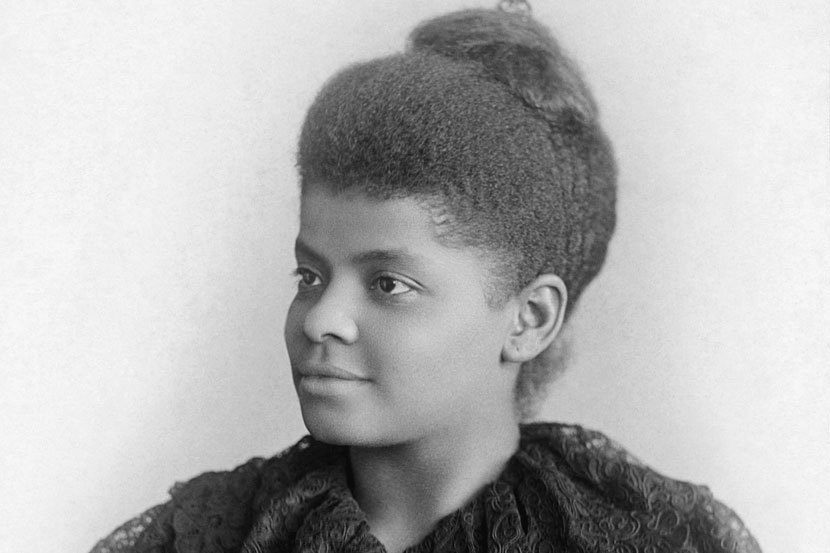

Gates: Honestly, I think the greatest challenge was finding the right balance and pace to convey the promise and achievements of the Civil War and Reconstruction, without making it too legalistic or abstract, while also neither shielding young readers from nor overwhelming them with the haunting violence of the period, from night riders to lynchings. The key, we found, was in highlighting characters, well and lesser known, who shaped this history in dramatic ways—from the soldiers Prince Rivers and Henry Jarvis to the pioneering investigative reporter Ida B. Wells. Telling their stories helped to humanize the struggle and capture in detail how Reconstruction advanced the American story, Jim Crow set it back, and African American citizens and their allies continued to press for freedom, dignity, and equality, even when it seemed least hopeful.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African American Research at Harvard University. An award-winning filmmaker, literary scholar, journalist, cultural critic, and institution builder, Professor Gates has authored or coauthored twenty-four books and created twenty documentary films. His six-part PBS documentary The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross earned an Emmy Award for Outstanding Historical Program–Long Form, as well as a Peabody Award, Alfred I. duPont–Columbia University Award, and NAACP Image Award. For Library of America, he has edited Frederick Douglass: Autobiographies and co-edited, with Paul Devlin, Albert Murray: Collected Essays & Memoirs and Albert Murray: Collected Novels & Poems.