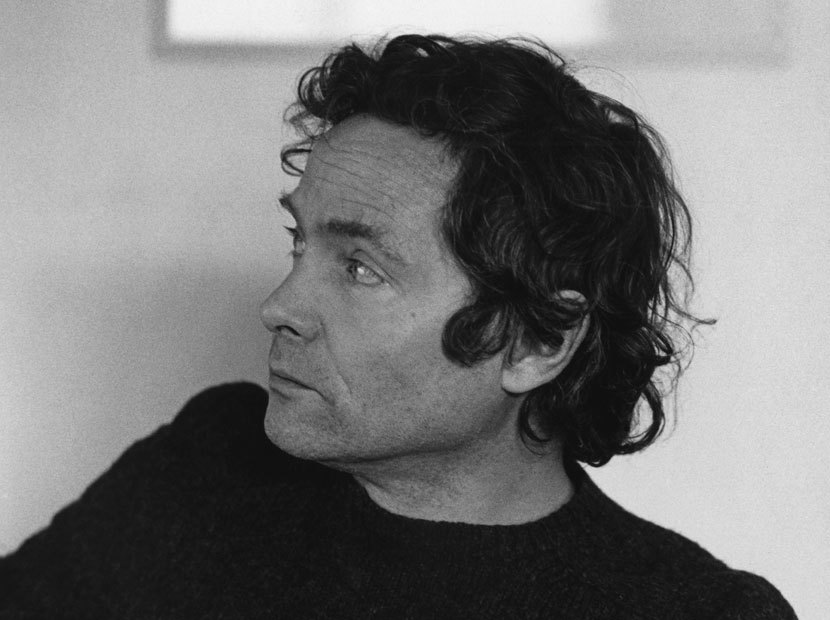

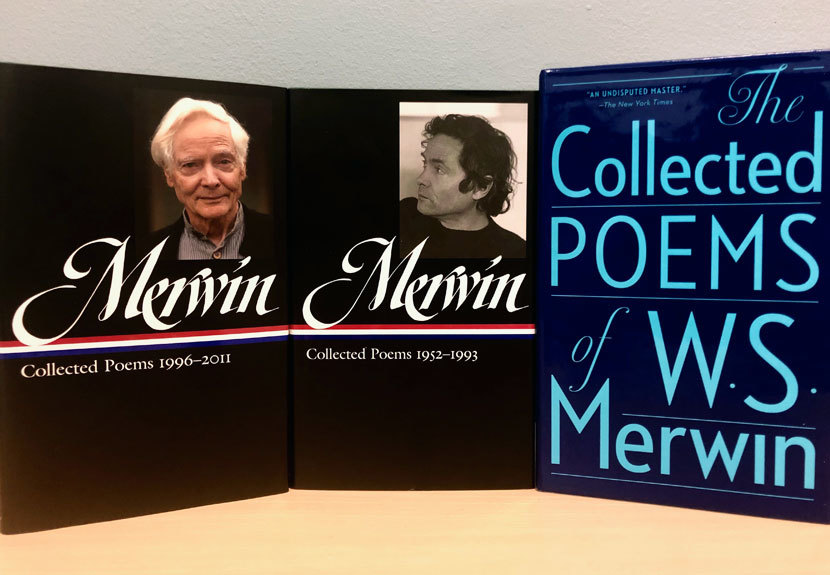

Library of America joins poetry lovers around the world in mourning the loss of W. S. Merwin, who died on Friday in his home state of Hawaii at the age of 91. Merwin enjoyed an exceptionally prolific and varied career that began when he won the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1952 and included two Pulitzer Prizes and a tenure as U.S. Poet Laureate in 2010–2011. In all, he published several dozen volumes of poetry and equally accomplished nonfiction, in addition to translations that ranged from Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Love Songs and a Poem of Despair to renderings of The Song of Roland and Dante’s Purgatorio.

In 2013, Merwin became one of only two living poets (with John Ashbery) to have his work published in the Library of America series. LOA President Emerita Cheryl Hurley remembers: “It was an honor to publish Merwin’s poetry in the Library of America, the first time we would issue an edition spanning the entire career of a living poet. Merwin had a particularly sympathetic rapport with the editor of the collection, J. D. McClatchy, which may have prompted Merwin, who by this time almost never left Hawaii, to travel to New York with his wife Paula to celebrate the launch of the edition. Unforgettable for us all, and Merwin himself seemed to very much enjoy the occasion.”

In an interview accompanying the release of the LOA edition, McClatchy said that Merwin’s verse “sounds like no one else’s. It possesses a unique originality, a range and depth, an eagerness to enlarge and experiment, combined with a love of tradition, that makes him such a powerful presence.”

Ecological themes became a notable recurring feature in Merwin’s poetry from the 1960s on, and later in life he embarked on a kind of second career as a conservationist. After moving to Hawaii in 1977, Merwin bought a former pineapple farm and patiently restored and enlarged the ecologically devastated property so that it is now a nineteen-acre palm forest, home to 480 palm species, including many that are rare or endangered. The Merwins established the nonprofit Merwin Conservancy in 2010 to preserve this legacy in the decades ahead. Writing in The New Yorker recently, Dan Chiasson tied the two strands of Merwin’s vision together: “As [Merwin] has held poetry to its essence, he has deepened it. . . . He also planted and tended a palm forest that is now permanently protected and open to the public. His poems, like that forest, are a kind of time preserve. Until you can make it to Maui, the poems will have to do. Many of them will be around as long as the palms.”

Critics, fellow poets, and other writers offer their thoughts on Merwin and his work below. (This page will be updated with additional tributes and remembrances in the days ahead.)

Harold Bloom • Forrest Gander • Maurice Manning • Bill McKibben • Françoise Palleau-Papin • Bill Porter / Red Pine • Robert Pinsky • Helen Vendler • Terry Tempest Williams

Harold Bloom

I knew William Merwin but only slightly until 1969, when we both lived near Washington Square in the Village. We became close during the 1970s, frequently dining together in the Village and discussing poetry and our mutual friends.

I introduced William in his readings many times in NYC and in New Haven. After he moved to Hawaii we stayed in touch by frequent phone calls and by a fairly extensive correspondence.

Either in reviews or in essays I wrote frequently on William through the years. He was the Proteus of American poets and he liked my calling him “The Old Man of the Sea.”

Together with the recent deaths of Richard Wilbur and John Ashbery, William’s departure ends one of the great generations of American poetic history, which included Elizabeth Bishop, James Merrill, and A. R. Ammons, among others.

There is so much poetry by William that time will have to sort it out. It is a fair surmise that scores of his poems will survive.

In his final phase William stripped away punctuation and most of the conventions of presentation. The poem concluding the splendid volume The Shadow of Sirius is one of my favorites:

The Laughing ThrushO nameless joy of the morning

tumbling upward note by note out of the night

and the hush of the dark valley

and out of whatever has not been theresong unquestioning and unbounded

yes this is the place and the one time

in the whole of before and after

with all of memory waking into itand the lost visages that hover

around the edge of sleep

constant and clear

and the words that lately have fallen silent

to surface among the phrases of some future

if there is a futurehere is where they all sing the first daylight

whether or not there is anyone listening

Forrest Gander

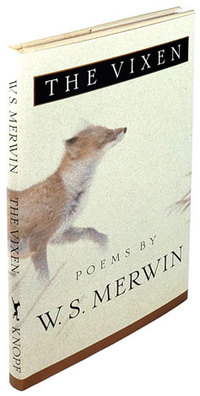

Remember the poem called “Substance” in Merwin’s 1996 collection The Vixen? A single, restless, unpunctuated run-on sentence; it would be easy not to notice it’s a sonnet. As often in his poems, Merwin situates distance, a spacial realm, within time: “behind the face of that time in its very days.” In fact, the real substance that the poem asserts, its mass—“the mass of the cow’s neck”—comprises a form of time, “the weight and place / of the hour.”

By insisting that time and place are part and parcel, Merwin’s poems ask us to see the world with an expanded imagination of our circumscribed place in it. “Substance” reminds us we’re not the logical arbiters of time’s value and substance’s extent. Nor is landscape external to us; it writes meaning into us even as we read meaning into it. The speaker of “Substance” struggles to perceive a world where animals and landscape go on, but he will not go on. Even though he “might reach toward it touching / the warm lichens the features of the stones,” Merwin can’t absorb the world nor make his own attributes coincide with those of time, for it is he himself who is contained by the world in time. If the poem intimates the speaker’s mortality, as so many of Merwin’s poems do, it likewise inspires in him a humility towards it.

Merwin wasn’t ever advocating that we align ourselves with rocks and plants in some primordial, inhuman stupidity. Nor was he sentimentalizing a paradise swept free of human intruders. Despite a long body of work in which he gave shape to his belief that other beings and things are enjoined in the structure of human selfhood, it is finally the quality of Merwin’s language which most emphatically advocates for a human place in the world. In his poems, Merwin’s underdetermined, unpunctuated syntax renews a plurality; it becomes the organ of a less ego-centered, less logic-driven perception. Merwin’s poetics are always expressing the possibilities of deep investment in attentiveness; they are insistently disclosing a quality of awareness through which we might imagine the potential of our lives in the world among others—human and not human—who call forth our responsibility as ethical beings.

Back to top

Maurice Manning

Sometime in the mid-1950s, W. S. Merwin wrote a poem called “Learning a Dead Language.” The opening lines suggest what he realized about the course of the rest of his writing life: “There is nothing for you to say. You must/ Learn first to listen. Because it is dead . . . .” I expect the dead language here was Occitan, the colloquial tongue of the twelfth-century troubadour poets, the originators of lyric poetry in the Western tradition. Merwin’s poem implies standing before the span of 800 years of poetic time to find one’s mysterious and vital connection to it. But the poem is more than that. It realizes the spirit of poetic expression survives even the death of the spoken language. Thus, paradoxically, poetry—the close kin of song—begins in silence, or emanates from an eternal Silence. That is how Merwin came to hear the poetry of the troubadours, and I suspect it’s how he came to hear his own poems as they trickled into utterance with increasing plainness and apparent simplicity.

Time, Presence, Absence, Thought, Nature, Light, and Shadow—these seem to me to be Merwin’s recurring themes, profound sources of contemplation that can only be glimpsed briefly and can only be expressed in what feels like a single exhalation. Of course, it takes a lifetime to refine the craft of poetry to such precision. And that’s another wonder I appreciate in Merwin: his poems utilize great precision to illuminate the dimensions of existence that forever remain indistinct and evasive. That’s one way to understand why poetry matters to some of us. In Merwin’s case, it’s also a way to realize how one may live in the world, and that is the larger, personal impact Merwin’s poetry has always had on me. Recently I was clearing some brush beside a stream on our farm and I watched the water trickle over a rock. The sunlight was at such an angle that the ripples cast shadows on the rock below, a slight movement, but constant and almost silent. The moment had all of the things a Merwin poem notices—light, shadow, motion, near silence, a sense of the eternal, a sense of a Presence one cannot name, and a sense that one is invited to belong to such a moment. This realm of the world is always inviting, it is where Being is both found and expressed, and the language we have for that expression is poetry. But it’s a language we have to learn from its Silence, and that requires a lifetime of listening.

Earlier in my own lifetime I was fortunate that W. S. Merwin selected my first book for the Yale Series of Younger Poets. The introduction he wrote was insightful and more than generous, and also rather daunting. I suppose he recognized some sort of talent, but I also think he recognized that I was starting my way toward understanding poetry in much larger terms. And that is true: poetry is larger than any individual poet’s expression or endeavor, it is its own province and our task is to learn how to reside in that mystical locale. More recently I was asked by Copper Canyon Press to write the introduction to the reissue of Merwin’s lovely meditation on the troubadours, The Mays of Ventadorn. Needless to say I felt outmatched, having never been to France and knowing only English. I have no idea if Merwin read my modest effort or had it read to him (because of his blindness), but it was an occasion for me to offer my gratitude for a man who leaves a living lesson for how one may live in this world. It is rare to have such a full-circle experience in this life. It is a plain gift, a treasure to receive and then to pass along to Time and to those who may be waiting for it.

Back to top

Bill McKibben

I knew William for many years—as a poet, but especially as a unique and effective environmentalist, committed to the defense of the gorgeous world we were born into. To visit him in Haiku, and especially to wander for hours through the palm jungle he had carefully cultivated on a patch of waste land, was to see that enchantment remains real even on our tired and anxious planet. He charmed so many things into existence.

Back to top

Françoise Palleau-Papin

Because your works are a gift we return to again and again, you are still alive, dear poet I’ve never met. In the photograph Cheryl Hurley sent me, you sit holding Paula’s hand at the Library of America reception in your honor. With your smile and clear gaze directly across from me, I feel a touch of joy and friendly spirit in the room as I write about you. Recognizing your talent in a long piece few had yet written about, the eminent scholar and poet John Burt showed the way when he published a seminal article on The Folding Cliffs as early as in 2000. Although I have also written on The Folding Cliffs, the beautiful long poem about native resistance to the deportation of lepers in the nineteenth century, I return again and again to two other books that I do not dare write about, as if they were too precious for me to add any critical discourse to their voice. One is a collection of poems, The Shadow of Sirius. The other is a collection of three prose portraits set in rural France, where you once lived: The Lost Upland. My favorite piece is a portrait of an old wine merchant, “Blackbird’s Summer.” It’s about transmission. Passing down before passing. About discerning what matters, and passing it on for others to hold. The grace of vision in the dark.

I’d like to quote one poem from The Shadow of Sirius, “Blueberries After Dark”—because it helps me mourn you. It’s also about a gift, in the sense of a talent, here transmitted from mother to son:

Blueberries After DarkSo this is the way the night tastes

one at a time

not early or latemy mother told me

that I was not afraid of the dark

and when I looked it was truehow did she know

so long agowith her father dead

almost before she could remember

and her mother following him

not long after

and then her grandmother

who had brought her up

and a little later

her only brother

and then her firstborn

gone as soon

as he was born

she knew

Université Paris 13, Sorbonne Paris Cité

Back to top

Bill Porter / Red Pine

Having tea with William was like sitting in a stream. He was like a stream, transparent and at the same time reflecting the world all around us. I felt the minnows nibbling on my toes. Tea never lasted long enough.

Back to top

Robert Pinsky

William Merwin’s poetry gave a pure, central realization of lyric poetry for my generation and many generations. The immediacy of the poems is mysteriously heightened by William’s intimate devotion to the past and to many languages.

He was extremely kind to younger poets. Many years ago, when I had laryngitis, he read from my Inferno of Dante for me at the Library of Congress, along with his own translation of the Purgatorio. An honor for me and a generosity characteristic of the man.

Back to top

Helen Vendler

W.S. Merwin was the author of the best one-line poem in the language:

ElegyWho would I show it to

He made plainness a virtue, and especially in The Lice created a new style—severe, taciturn—of political protest. Long before the rest of us, he saw ecological danger in prospect.

Back to top

Terry Tempest Williams

Merwin. Ides of March. His passing.

Here, now, without William, the world feels less safe, less generous, less everything. He was always present, watching, writing, being. The palms he planted, the poems he wrote, the life he lived by hand and by heart—remind us the way and practice of attention.

I keep thinking of his line, “We are asleep with compasses in our hands.” His poems are our awakening to the beauty before us.

Back to top

The Merwin Conservancy is accepting donations in Merwin’s honor.

More on W. S. Merwin

The American Scholar: John Kaag interview with W. S. Merwin

New York Review of Books: “Whole Earth Troubador” by Ange Mlinko

The New Yorker: “The Final Prophecy of W. S. Merwin”

The Paris Review: “Crashing W. S. Merwin’s Wedding” by Ed Hirsch | “Letters from W. S. Merwin” by Grace Schulman