The early novels of John O’Hara, like those of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, with whom he was often grouped by mid-century critics, dramatize the longings and dashed hopes of a lost generation, seduced and betrayed by the glittering temptations of the modern age. That O’Hara’s literary stature has failed to match that of his more famous contemporaries has much to do, ironically, with his special gift as a writer. Where they were given to grand symbolism and flights of lyrical imagery, O’Hara remained always very much grounded in the real world, in “society,” exposing its fine details and unspoken rules. For Fran Lebowitz, O’Hara is “the real Fitzgerald,” the Jazz Age’s truest, most unblinking literary chronicler.

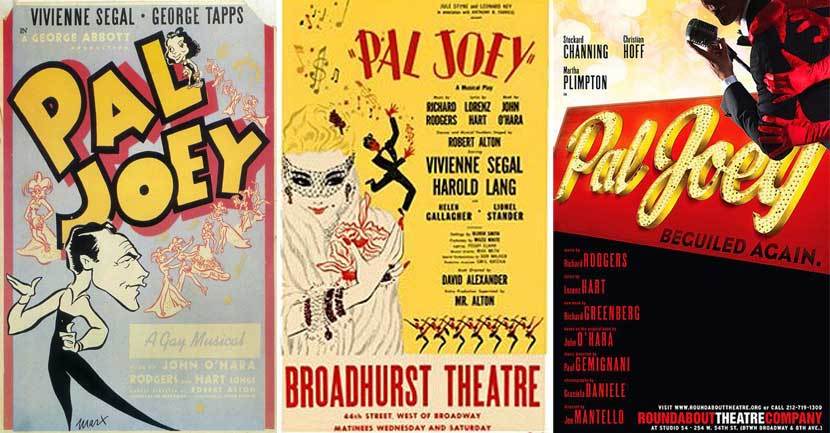

Now, with John O’Hara: Four Novels of the 1930s, Library of America and editor Steven Goldleaf offer readers an opportunity to reassess the genius of this still-underappreciated American writer. Here, gathered in one volume for the first time, are O’Hara’s first four works: the landmark debut Appointment in Samarra (1934), #22 on Modern Library’s list of the top 100 novels in English; Butterfield 8 (1935), one of the franker portrayals of female sexuality in our literature; the long out-of-print Hope of Heaven (1938), a noirish Hollywood novel inspired by O’Hara’s first stint as a screenwriter; and the pitch-perfect Pal Joey (1940), an epistolary novel in fourteen parts (most written in the 1930s) that provided inspiration for the enduring Rodgers and Hart musical.

We caught up with Goldleaf, a professor of English at Pace University and author of an acclaimed study of O’Hara’s short fiction, to talk about this still underappreciated American writer.

Library of America: John O’Hara: Four Novels of the 1930s is a companion to Library of America’s 2016 volume of O’Hara’s short stories, a form in which he excelled. What did novels allow O’Hara to do that he couldn’t in his shorter fiction?

Steven Goldleaf: O’Hara was a master of the elliptical, especially in his short stories. He would present a slice of life there, with no prefatory explanations of how that slice came into being and, often, he would end the story without an explicit explanation of what the story meant, how the author wanted it interpreted, or how the events resolved themselves. After O’Hara, elliptical content became a common quantity in later New Yorker stories, as practiced by J. D. Salinger (“A Perfect Day for Bananafish” is the quintessential unresolved New Yorker story) or Shirley Jackson, whose famous ending to “The Lottery” in the New Yorker bedevils readers to this day.

O’Hara’s early success with the novel form exploited the Goldilocks principle: they’re just right. Appointment in Samarra, for example, takes place over the course of a few days with a very limited set of characters—it can easily be re-imagined as a very long short story, given its abbreviated scope spatially, temporally, and thematically. It’s basically an expanded form of a short story about the crucial final day of Julian English’s short life, with occasional diversions onto minor characters such as the Fleiglers or Al Grecco, or its flashbacks to Julian’s and Caroline’s early romance.

O’Hara’s early novels grow more and more complex, structurally—the scope of Butterfield 8 is a bit longer than Appointment, taking place over weeks rather than days, and Hope of Heaven expands that scope to months rather than weeks. The next true novel O’Hara wrote (Pal Joey being a collection of linked stories with common themes and a common main character but not a wholly pre-conceived structure: if some Pal Joey stories had been omitted or rearranged, no one would have been the wiser), the 1949 A Rage to Live, transpires over decades, as did several of O’Hara’s long generation-spanning novels of the 1950s and 1960s, which allowed him increasingly to flesh out the etiology of multiple narratives placed against a backdrop of history, a subject that fascinated O’Hara.

LOA: O’Hara’s remarkable ear for American speech, already evident in his first novel, 1934’s Appointment in Samarra, is one reason why the book feels very modern today. (We’re thinking, for instance, of the roadhouse scene in Chapter 6, a social catastrophe that unfolds almost entirely in dialogue.) Where did O’Hara develop this talent, and was it much remarked upon at the time?

Goldleaf: Like so many of his writerly characteristics, O’Hara’s ear for dialogue was recognized and praised early on in his career, so much so that he grew to resent the praise: he felt that some critics wanted to reduce him to a sort of a mechanical recording device, dwelling too exclusively on his gift for capturing the American vernacular. He bristled at all such over-simplified characterizations of his work, but that one rankled him especially. He felt strongly that he was doing much more than just parroting how we spoke—he was sure that the sum of these verbal tics added up to who Americans were as a people and as individuals.

He was a great listener. He would pick up on tiny things in Americans’ diction and syntax, and render them accurately in his dialogue, little things like the slightly patronizing way some upper-crust Northeasterners pronounce the words “not at all,” which he would render as “not a tall,” or he would capture the way even educated Americans misused pronoun case at times. A certain college-educated type, he would assert, would persist in saying things like “. . . between you and I,” while other, more highly-educated speakers would know to use “between you and me” unfailingly. O’Hara was sometimes characterized, reductively, as a writer of “classism” in America, as if there were only two or three or four classes of Americans.

What O’Hara did was recognize that those broad groupings could be broken down further into sub-groups and sub-sub-groups and finally individuals, noting each individual’s background and influences and personality type that added up to an explanation of the ways they spoke, wrote, and thought. He was merciless in recognizing the large role that someone’s past retained into his present, and rather than excuse a verbal slip into a slightly different speech-register as an aberration, he would seize upon it as a revealing clue to that person’s underlying nature. He jokingly described himself as “Dr. O’Hara” and his writing room as his “laboratory” where he conducted “experiments,” but he wasn’t entirely joking—he truly felt that his work was to perceive verbal mannerisms that got straight to the root of each character’s true nature.

LOA: Butterfield 8 (1935) had to wait for sixteen years to be published in England due to its perceived indecency. What do you make of John Updike’s theory that what bluestockings found most objectionable in O’Hara was “his insistence on crediting his female characters with sexual appetites . . . independent of male desires?”

Goldleaf: Updike was a sharp critic, maybe more perceptive in his reviews and criticism than he was in the genres he’s better known for, and he read O’Hara particularly well. Empathy was O’Hara’s driving force, almost his obsession. When he had the slightest difficulty understanding why people behaved the ways they did, he avoided doing what most people, and many writers, do, which is to focus on people whom he understood better.

Instead, O’Hara would try to get inside the skin of those he didn’t understand immediately, and for a male heterosexual, this meant putting himself in the place occupied by women in our society. Many of his novels and stories about Hollywood, and Broadway, are prescient testaments of the #MeToo movement, told from the perspective of actresses who find early on in their careers that the road to success runs through the casting couch. He’s surprisingly non-judgmental of these women (and sometimes gay men) for using their bodies to achieve their career objectives, showing instead how the entertainment business exploits their ambitions. The bodies of these young, attractive people are sold and traded as a commodity without a consideration of the essential immorality of treating them as sex objects.

O’Hara empathizes with (rather than criticizes) these characters’ choices. He is the most empathetic of writers, and I think this sense of empathy gave him insight into all sorts of characters whose experiences were far from his own. The promiscuous Gloria Wandrous, based on the notorious Starr Faithfull, was one such character O’Hara understood. Instead of showing women and men with strong sexual drives as aberrant or disgusting, he showed his readers how they might identify with them, and to feel emotions that they otherwise would have repressed, or even have been hostile to.

LOA: In Butterfield 8, O’Hara also handles the sexual abuse of a child with a frankness that’s still startling today. Why was this sequence so important to O’Hara’s conception of his main character, Gloria Wandrous? Did he have to fight his publisher to keep it in the book?

Goldleaf: Like many writers—Dreiser in the 1900s, Roth in the 1960s come straight to mind—O’Hara fought against the constraints of publishers, and of the reading public, in choosing subject matter that scandalized polite society. The taste and tolerance of both the public, and the publishers who reflect those tastes and tolerances, has always been hypocritical, to a greater or lesser degree. People have always spoken, and certainly have always thought, more crudely than they permit others to speak, and writers have long struggled with their impulse to express the thoughts and deeds that have been kept out of print.

O’Hara courted controversy with his choice of subject matter—sexualized women, risqué situations, wrecked marriages, rape, casual adultery—and the blunt way he often wrote about it. It made no sense to write about a “loose” woman such as Gloria in a coy way, that hinted obliquely (if at all) at the causes of her sexual freedom, at the anger and puzzlement she felt as an abused child, how she schemed to turn her sexuality to her advantage, only to cause her own destruction. To O’Hara, that would make as little sense as explaining a shooting without being permitted to describe a gun, or how a gun works, or even to use the word “gun.” He needed to show what had happened to Gloria, and he needed to use the language that people actually used in describing it.

LOA: Of the four works collected in this volume, readers will likely be least familiar with 1938’s Hope of Heaven, which centers on the troubled romance of a Hollywood screenwriter. Does Hope of Heaven have any affinities with any contemporary works set in 1930s Los Angeles, like Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon, or Daniel Fuchs’s Hollywood stories?

Goldleaf: I’d say its closest resemblance would be to Budd Schulberg’s What Makes Sammy Run?, in that its protagonist is a working screenwriter (West’s is a painter, Fitzgerald’s a studio executive, though all four authors worked extensively as contract screenwriters themselves). O’Hara was a friend of Schulberg (and less personally, a friend of Fitzgerald), but his alter-ego Jim Malloy doesn’t really spend much time working at his craft the way Schulberg’s characters do.

All three, Locust, Tycoon, and Sammy, portrayed the screenwriters’ life as exploitive and artistically crushing, but O’Hara’s version is much less castigating: Malloy is shown to be doing a simple job of work, reasonably well-compensated for it and reasonably competent at it. Hardly any of the novel concerns Malloy’s working life—mostly, the brief scenes of him in his studio office have him making and taking phone calls from the characters involved in his complicated personal life, arranging to take them out to lunch where he can show off his familiarity with famous actors.

Oddly, for a man whose temper was famously volatile, O’Hara seems by far the least angry of these Hollywood novelists, whose novels about the movie industry are largely bent on the goal of exposing the business’s nastier side and its crass rejection of artistic virtues wherever they threaten ticket sales. O’Hara is pretty well reconciled to Hollywood’s bottom-line mentality as a given, and rails against it the least of all writers who accepted its salary in exchange for their abilities.

LOA: Pal Joey (1940) inspired the successful Rodgers and Hart musical that featured one of their most famous songs, “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.” What might readers who only know the stage version be surprised by in O’Hara’s original?

Goldleaf: The Pal Joey stories were a crucial turning point in O’Hara’s career. Through the late 1930s, as a struggling young writer, he made a living at it, but was constantly hustling for assignments, trying to pitch ideas to editors, taking on chores such as lucrative short-term contracts writing for movie studios, but Pal Joey caught on with admiring readers, one of whom was the editor of the New Yorker, Harold Ross, who encouraged him to keep writing more of them, just as O’Hara had begun to tire of the character. Ross had already published dozens of his stories by the time O’Hara wrote his first few Pal Joeys, but not on his own judgment as much as on the strong recommendations of his fiction editors, Wolcott Gibbs and Katherine White. Ross famously complained that he would never accept another O’Hara story that he didn’t understand.

When Ross surprisingly clamored for more, O’Hara was glad to produce Pal Joey stories on demand, appreciating his good fortune in finally getting Harold Ross on his side, but the more stories he produced, the more tedious he found the character growing to him. The technique O’Hara was using, the ironic monologue, was derivative of past masters such as Ring Lardner and Dorothy Parker, whose characters unwittingly revealed their deeply flawed personalities, although by this point in his career, O’Hara’s felt he could crank these stories out with his left hand, while his other more innovative methods went underappreciated.

| ALSO AVAILABLE |

|

| John O’Hara: Stories |

But the development of the short stories into the basis of a musical, combined with the talents of Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, turned the property into a gigantic financial windfall for O’Hara, who also wrote the musical’s book, the non-singing portion of the play. Financially, the musical Pal Joey allowed O’Hara for the first time to disregard his previous dependence on editors’ desires and tastes and also to re-think what his artistic goals ought to be. And of course, the success of the musical added to his self-esteem and his lifestyle. From then on, O’Hara lived like the wealthy, prosperous author that he was, although he continued to think of the Pal Joey stories themselves as being of limited artistic merit (except when anyone other than he expressed that thought).

Actually, he began to think of himself, somewhat to his detriment. as primarily a writer of first-rate dialogue, which he was, but mostly for the written page. On the stage, the subtle touches of his dialogue were less effective. For the remainder of his life, O’Hara wrote plays that he couldn’t get produced, despite the track record of Pal Joey. This investment of his time and skill proved frustrating to him, although by almost anyone’s standards, O’Hara still continued to be tremendously productive in the two genres of his greatest success, the novel and short story.