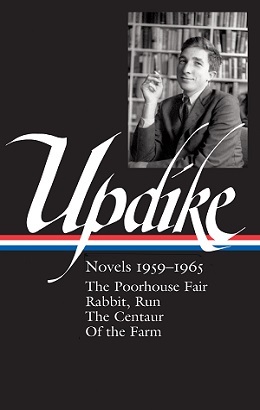

Last month when we interviewed Christopher Carduff, editor of our new volume John Updike: Novels 1959–1965, he told us that the four books collected in it, all set in the eastern Pennsylvania of Updike’s youth, “hold together, very loosely, as a set. They are four buckets drawn from the same well, the seemingly bottomless well of Updike’s early impressions of life. Updike would later return to a Pennsylvania setting in his fiction, poetry, and memoirs, but seldom with the intensity that is exhibited here.”

Curious to learn more about what Updike himself once referred to as his “Pennsylvania thing,” we turned to Jack De Bellis, professor emeritus at Lehigh University and the author of six books on John Updike, for further insight into the small-town milieu that proved to be such an abiding source of inspiration for the author.

Library of America: For the benefit of our readers, can you describe the part of eastern Pennsylvania where Updike grew up and where these four novels take place?

Jack De Bellis: John Updike was born March 17, 1932, in West Reading, Pennsylvania, and lived in Shillington, an eastern suburb of Reading, thirty-five miles from Philadelphia, until 1945 when his family moved to his mother’s parents’ Plowville farm a dozen miles south of Shillington. All three towns are in Berks County. Berks County, described as “diamond shaped” by Updike, is just north of the Amish country. Berks’ northern tier is filled with slag heaps from coal mines, but its southern section has rolling hills and farms painted red with traditional hex signs. Shillington (fictional Olinger) lies at the foot of Mt. Penn (fictional “Mt. Judge”). Updike’s first four novels are infused with Berks County’s streets, schools, stores, churches, movies, newspapers and museum. Reading is famous for its red brick row houses, in Rabbit Angstrom’s imagination, the “flowerpot red” city.” Though Updike named it “a muscular, semi-tough” city, he charted its decline throughout the Rabbit tetralogy. Reading is distinctly urban and lower-middle class, while Shillington is upper-middle class. Although Updike treated other locales in his nearly sixty books, he returned very often to Berks in his fiction, poetry, and essays. He even wrote a play about Pennsylvania’s only president, James Buchanan.

LOA: What professional sports teams did Updike follow?

De Bellis: From childhood Updike played baseball with Shillington High School stars Barry Nelson and Gerry Potts. He followed the Philadelphia Phillies and Athletics baseball teams, clipping their box scores from the Reading Eagle, and watched a few Athletics games at Shibe Park, mainly to see his idol, the Boston Red Sox’s Ted Williams. After Updike moved to New York and Massachusetts in the ’50s, he pursued Williams’s career, and in 1960 he watched Williams’s last game—and last home run. His essay about that game, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” is often named the finest baseball essay ever written. Updike played basketball in school, and star Barry Nelson showed him how to make hook shots and confirmed, “he could put ’em in.” When Updike was about thirteen he saw many games featuring Bob Arndt, and used him to create his greatest character, “Rabbit” Angstrom, who has been likened to Huckleberry Finn as an archetypal American.

In college Updike discovered golf and it became a lifelong passion; he played with his sons just weeks before he died. Updike’s Rabbit tetralogy is replete with scenes treating baseball and golf. His astute and witty golf stories, essays, and poems are collected in Golf Dreams. In his book of memoirs, Self-Consciousness, he describes his ability to ski and to play football and volleyball.

LOA: Do you agree with Updike’s biographer Adam Begley that Updike was “very much preoccupied with Plowville, Shillington, Reading, both in his stories and in his novels”?

De Bellis: Adam Begley is certainly correct. The impact of Berks on his feelings and creative consciousness cannot be overvalued. Though Updike left Shillington for Harvard in 1950 and a few years later moved to Ipswich, Massachusetts, he frequently returned to Shillington for high school reunions (he was the class president), summer vacations, and to keep in touch with classmates. These visits honed his memories of the area and would make their way into his work. In Self-Consciousness, in “A Soft Spring Night in Shillington,” he writes, “I loved Shillington . . . as one loves his own body and consciousness because they are synonymous with being.” In contrast, New England taught him “how drear and deadly life can be.”

LOA: How would you say Updike’s intimate familiarity with Berks County shaped his sensibility?

De Bellis: Updike’s first grade teacher labeled him a genius, so his sensibility and brilliance must have been innate. His Shillington experiences enabled him to transform this sensibility into a magnificently expressive language. In a very late poem Updike extolled Shillington for giving him as a writer,

all a writer needs,

all there in Shillington, its trolley cars

and little factories, cornfields and trees, leaf fires, snowflakes, pumpkins, valentines

To think of you brings tears. . . .

Shillington was the concrete world of his childhood that he turned into unforgettable sensory images. In the same poem Updike cherished Berks for providing a “sufficiency of human types” who would people his universe with memorable characters. Since he was given many years to observe the alterations in that universe, Updike could record, with a kind of objective sympathy and an elegiac tone, the county’s slow demise.

LOA: And how did Updike’s upbringing in eastern Pennsylvania influence The Poorhouse Fair, Rabbit, Run, The Centaur, and Of the Farm?

De Bellis: Updike’s first four novels represent what he called “that Pennsylvania thing.” Each book is set, respectively, in places familiar to Updike from boyhood—the nearby poorhouse, the Shillington streets, the Shillington High School, and the Plowville farm. Each novel brims with vivid detail. The Poorhouse Fair is set in the Diamond County Home for the Aged, modeled on the poorhouse on Philadelphia Avenue down the street from Updike’s home. Updike treats the poor inmates realistically but with empathy, particularly when they are overwhelmed by irritating administrative restrictions. Their spokesman, John F. Hook, was based on Updike’s grandfather, John F. Hoyer, and the other novels’ heroes are composites of family members.

Updike remarked that Rabbit, Run was a way into “the matter of America,” and that “matter” was composed of images of the streets, golf courses, and eateries of Shillington. So real is Shillington for Updike that a map of his hometown corresponds to a map of Rabbit’s Mt. Judge. He also based his central character, ex-high school basketball star Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, on a Shillington High player, Bob Arndt, whom he had admired in the 1946–47 basketball season.

However, Rabbit is a decade beyond his stardom and drifting, like other ex-athletes Updike noticed in Shillington. Updike has wondered if he might have become like Rabbit had he not gone to Harvard and become a successful writer. So can one consider Rabbit to be Updike’s negative alter-ego?

Updike’s most personal, comic, and experimental early work, The Centaur, is also the most “Pennsylvanian” of the four novels, with many composite characters who were readily identified by Updike’s classmates. The streets and shops of Olinger are instantly recognizable as parallels for Shillington. The principal setting of The Centaur is Olinger High (Shillington High School, where Updike’s father, Wesley Updike, taught), and the narrative’s conflict between George Caldwell and his son Peter matches Updike’s experiences when was fifteen.

Of the Farm completes this quartet of novels, which have been based in turn on Updike’s grandfather, his alter-ego, his father, and now, in the figure of Mrs. Robinson, his mother. Although treated with understanding, she is described less sympathetically than the other outsiders: John F. Hook, “Rabbit” Angstrom, and George and Peter Caldwell. Like The Centaur, Of the Farm is a coming-of-age novel, but with a twist. Instead of a young boy involved in a struggle with his father, the hero, Joey Robinson, is established and has left his first wife, and remarried. He goes to the farm to seek his mother’s approval, but Mrs. Robinson thinks that Joey has wasted his life—she intended for him to become a poet and to spend his days on the farm—and his choice of a new life confuses and angers her. Joey’s extrication from his mother’s plan is achieved only with the help of his wife. Like the other autobiographical overtones in the previous novels, one can infer the emotional problems Updike himself faced in following his dream “of riding a thin pencil line out of Shillington, out of time altogether, into an infinity of unseen, even unborn hearts,” as he wrote in his memoirs.

LOA: At the urging of Updike’s mother, the Updike family left Shillington in 1945 for a farm in Plowville which had belonged to Updike’s grandparents; it was sold during the Depression and his mother dreamed of buying it back. Updike lived there while attending high school and after graduation often visited. How did this affect Updike personally and the writing of Of the Farm?

De Bellis: Updike felt quite dislocated by the move from urban Shillington to the Plowville farm. He hated farm duties and missed his friends. Also, instead of biking around Berks he had to depend on his father to drive him to and from school. His after-school nighttime activities were affected as well.

Nevertheless, Plowville’s isolation afforded Updike time to read, draw, and write, and the 300+ items he published in the school paper, Chatterbox—drawings, prose, and verse—attest to the fact that Plowville was the incubator of Updike’s extraordinary talent. Updike’s epigraph to Of the Farm (desiring your own freedom requires that you desire the freedom of others—I’m paraphrasing Sartre here) suggests the novel’s central theme and it could serve as a controlling idea for this quartet of Pennsylvania novels. Though he moved his own family to New York and then Massachusetts seeking the freedom to write, Updike’s heart would always be in Shillington where he refreshed his art with the ideas of freedom and transcendence within the personal world he loved. Religious all his life, Updike continued to focus upon how the deepest penetration into the physical details of his town could enable him to find “God’s fingerprints” in the simplest things. This was a lifelong pursuit and it began where he grew up, in Shillington and Plowville.

LOA: Did you ever meet Updike? Can you tell us something about your own work on him?

De Bellis: My first encounter with John Updike’s work occurred in 1960 when I reviewed Rabbit, Run for my Los Angeles radio program, while teaching at UCLA. Twenty years later I asked his permission to use several poems for a “Visual Poetry” exhibit I curated. I was flattered that he not only consented but that he permitted me to correspond with him; eventually he aided my research by sending me personal files and documents. I met him on several of his speaking engagements and was fortunate enough to have him as a guest in our home. He also wrote introductions to two of my books and autographed a great many. He struck me, as he did so many, as charming, forthright, immensely articulate and empathic.

I was stunned when John died on January 27, 2009. It seemed intolerable that a man so palpable and whose writing was so dependably a part of my life should suddenly vanish. I would no longer be able to read his stories, poems and reviews in The New Yorker, or anticipate new novels. Nor would I chuckle at his distinctive wit as he read at nearby colleges or venues where he received awards. He would no longer be a televised presence in my home on C-Span or PBS. Letters and postcards from him laden with his pointed remarks couched in his patented magic would cease. To me he seemed as reliable as the sunrise. I felt his passing to be a personal deprivation.

My involvement with Updike has occupied my forty-year teaching career, my scholarly writing, and my efforts to help launch The John Updike Society and The John Updike Review. As a teacher, I incorporated Updike into my courses, from first-year to graduate seminars. As a writer, while in graduate school I authored several reviews of Updike’s fiction for The Sewanee Review, and published in other journals. I compiled a bibliography of all his work, John Updike, 1967–1993: A Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Sources (Greenwood Press, 1994), then revised and updated it with Michael Broomfield, co-author, as John Updike: A Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Materials, 1948–2007 (Oak Knoll Press, 2007); a supplement has been prepared. I authored The John Updike Encyclopedia (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001) and later John Updike’s Early Years (Lehigh University Press, 2013) and edited two collections of essays, John Updike: Critical Responses to the “Rabbit” Saga (Praeger, 2004) and John Updike Remembered (McFarland, 2017).