A look at the index for Library of America’s new anthology Dance in America reveals more entries for George Balanchine than for any other individual. In the following guest contribution, the book’s editor, dance critic Mindy Aloff, explains why Balanchine was and is such an irresistible subject for writers on dance. (Click here for our interview with Aloff about Dance in America.)

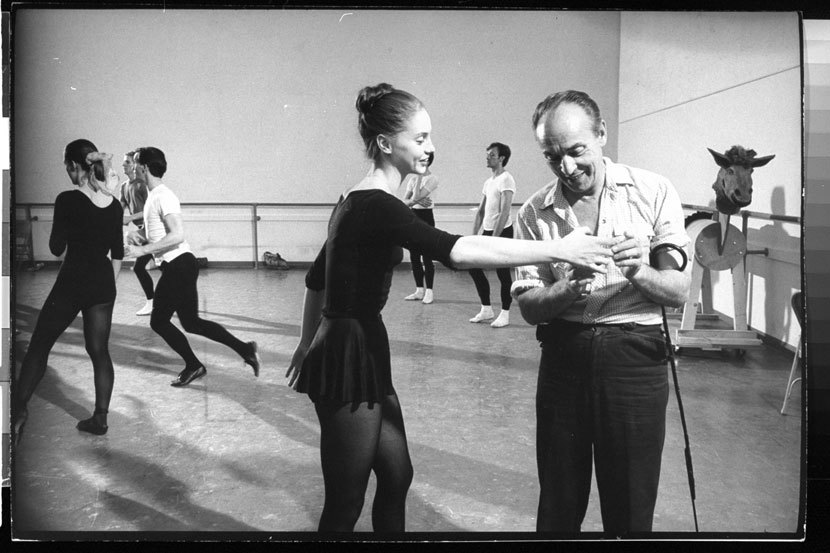

The difference between Balanchine and most other prolific theatrical choreographers in America whose work we know firsthand is that Balanchine was as interested in teaching great dancers how to be greater in daily class as he was in choreographing for them. He wanted to see how far classical dancing could push the dancers’ technical capacities and how deeply the classical syntax and vocabulary could be explored on their own terms. (Around the 1960s, he also worked with some of his faculty at the School of American Ballet to develop syllabi for children’s classes—syllabi still in use.) Balanchine’s NYCB company classes were a kind of laboratory about the classical language, the very core of his art. Perhaps his most astonishing goal was to see the dancer’s legs and feet encouraged by speed and repetition to become capable of effects as nuanced as those of arms and fingers. This led him to conceive of the ballet body as divisible vertically, expressive on each side from head to toe, rather than to assign all demonstration of emotion above the waist and all realization of action below—the division unquestioned by ballet pedagogues for centuries. He has been compared with Shakespeare, for his abilities as a dramatist, but the comparison could also speak to the changes that both artists rang on the artistic language they inherited, refined, and vigorously enlarged.

Unlike Shakespeare—who, in addition to his prowess as a storyteller and his mastery of character and wit, invented vocabulary—Balanchine would say that there are no new steps in ballet, only new combinations. Yet his recombinings have the legacy of innovation, and even audiences who know nothing about ballet as a formal system and an expressive instrument can sense that this person “spoke” this language with inventiveness as well as fluency. To writers, that is fascinating, more like James Joyce than Shakespeare sometimes.

For me, Balanchine’s peer in commitment to teaching was Martha Graham, something that Lincoln Kirstein understood, now cheering her (as in his essay in this anthology), now excoriating her. In contrast to Balanchine, who inherited the classic language he expanded and deepened, Graham invented her own dance language—as, it could be argued, did Katherine Dunham (through her meshing of ballet and modern dance with elements of dances from Africa and the Caribbean) and also Isadora Duncan (whose life and career are narrated with pleasure in _Dance in America by Bob Gottlieb and whose late performance style is described by Hart Crane). In our anthology, Stuart Hodes presents Graham in the classroom and his own student efforts to meet her demands in gobsmacking detail. Dunham’s entry speaks about transferring to Broadway her anthropological studies of “primitive” dances, interwoven with Western theatrical dance practices. Duncan’s entry explains how a dance might originate from imagination and perception, from mental images of abstracted natural elements and actual observation of “the laws of nature,” as she learned to know them in her native California during the late nineteenth century.

Nevertheless, within even this exclusive group of American dance geniuses, Balanchine’s ideas regarding choreography and technical training, his images, the Mozartian heights and Pushkinian depths of his storyless stories, his educated musicianship and intuitively musical sensibility, his repertory of charismatic ballets, all set him apart in his own field and, for some audience members, among geniuses in other arts. For subsequent generations of dancers and audiences and in companies throughout America and around the world, even thirty-five years after his death he remains Balanchine, Our Contemporary.

In the twenty-first century, it seems increasingly the case that Merce Cunningham—who also used teaching as a language laboratory and whose creative powers also poured forth in conjunction with his practice of technique (which he discusses in his entry here and which Robert Greskovic meticulously analyzes in a theatrical example)—was the same type of artist in this respect as Balanchine, Graham, and, at periods in their careers, Duncan and Dunham. I’m not speaking of creative genius, as such, but rather of their creative process, in which teaching was central to creating. In America, Fred Astaire, Paul Taylor, Jerome Robbins, Twyla Tharp, Léonide Massine, Antony Tudor, Fayard Nicholas, Mark Morris, Alexei Ratmansky, and many others with a foothold in our anthology as authors or subjects of entries are or were choreographers of genius. America has been quite lucky with the dance nurtured here in the past century and a-quarter. Many creative geniuses have taught as well, in ballet, notably Massine and Tudor. But the continuous synergy between the experiments with technique in studio classes and creativity on the stage, which marks this particular kind of choreographic imagination, is, by my lights, distinctive to the point of exclusivity. And as Graham herself, watching NYCB dancers in Serenade, was moved to appreciate, Balanchine’s command of ballet put him proverbially alone in the forest, albeit while also speaking Russian, French, German, and—as his entries in the anthology suggest—a basic English peppered with wit.

In terms of serving as his company’s artistic director—a separate job from being its teaching and creating ballet master —he was also without peer in American ballet for his theatrical wisdom in choosing scores for himself and other company choreographers—that is, in his understanding of which music, from all centuries, magnetizes audiences and which elements within a piece of music bring forward the eloquence of classic dancing most powerfully and persuasively. In the arts, you can’t dig deeper into the human psyche than a connection with music. As our contributor Ruthanna Boris, one of Balanchine’s earliest American dancers, a choreographer herself, and a practitioner of dance therapy, often observed, Balanchine trusted his subconscious. That trust freed his dancemaking to light up entire constellations of connection between what one hears in the theater and what one sees. For a couple of hours, one succumbs to the illusion that the crazy, wounded world has been made whole, healed into sense, by an art dependent upon painstaking physical analysis, turnout, and the toe shoe. Nor did he let his amazing capacity to change his work for practical reasons, without attachment to what he was changing, get in the way of his energies for generating art that audiences could absorb and feel without the need for program notes or outside explanations.

On the level of craftsmanship, he made some of the most brilliant and evocative variations for men in the history of ballet, and his choreography put feminine beauty on a pedestal and challenged the techniques and stamina of most of the women in his ballets respectfully; sometimes, his choreography for ballerinas has an undercurrent of sacred devotion. He is one of very few ballet choreographers in living memory who did not insist on his ballerinas being overpartnered. Also, he treated the little children in his works with grown-up seriousness of purpose, assigning them real responsibilities as dancers and endearing their presence to audiences through the formal charm of comparing and contrasting their proportions to those of adults.

Finally, he didn’t use his ballets to make political points or to play out agendas. When performed as he wanted them performed, his choreographies give one the sense that their running times—their lives as entertainments that happen to be works of art—are but a dream indeed, that their ends are literally in their beginnings. Quick now, here now, always.

Balanchine permeates American dance, even now. One reason may be that he had the biggest view of it. Take his definition of dancing itself, which potentially accommodates not only all theatrical forms but also studio experiments, hockey players, the differently abled, children—everyone. As Suki Schorer, Balanchine’s mentee as a pedagogue and one of his principal dancers, and writer Russell Lee have put it: “Balanchine had a concise definition of dance. He said it is movement of the human body, in a limited space, in relation to time.” By this measure, even a reader hastening to turn a page before the theater’s lights lower, dances.

Please note that Anna Kisselgoff, whom I identified in the first of these interviews as having retired from The New York Times in 2005, stepped down as Chief Dance Critic in that year, but wrote assorted pieces for the paper for one more year, retiring in 2006.

Mindy Aloff is Dance Editor of The University Press of Florida and has taught dance criticism and history at the Macaulay Honors College of CUNY (at Hunter College) and at Barnard College. She is a former editor of the Dance Critics Association News and serves as a consultant to The George Balanchine Foundation. The author of Dance Anecdotes: Stories from the Worlds of Ballet, Broadway, the Ballroom, and Modern Dance (2006) and Hippo in a Tutu: Dancing in Disney Animation (2008) and the editor of Agnes de Mille’s Leaps in the Dark: Art and the World (2011), Aloff has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Village Voice, and The New Republic, among many other outlets.