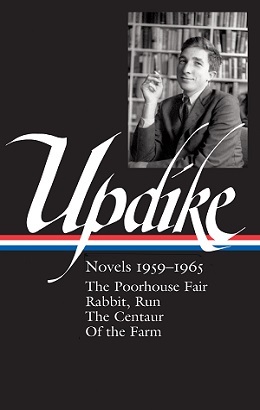

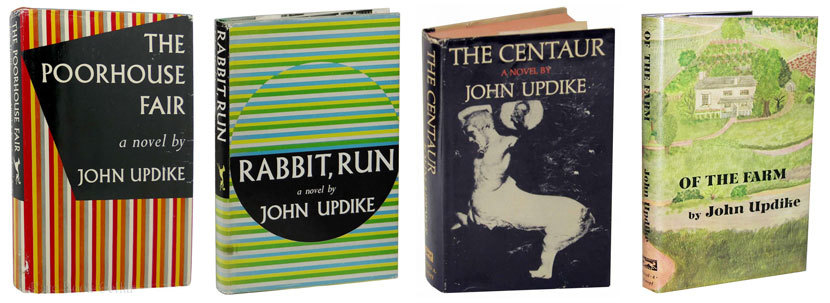

Library of America’s John Updike edition enters a major new phase this month with the arrival of John Updike: Novels 1959–1965, which collects the four early works that mine the author’s formative years in small-town Pennsylvania: The Poorhouse Fair (1959), Rabbit, Run (1960), The Centaur (1963), and Of the Farm (1965).

Like LOA’s previous Updike titles (the two-volume Collected Stories and Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu), the new book is edited by Christopher Carduff, Books Editor of The Wall Street Journal and a former member of the Library of America staff. He also edited LOA’s edition of the works of William Maxwell.

Below, Carduff shares his thoughts on how the new volume came together, the common origins of these four novels, and their place in the overall arc of Updike’s prodigious career.

Library of America: Before he died, in January 2009, Updike named you the editor of the Library of America edition of his works. Could you talk a bit of how this came about, and of what guidance he gave you in preparing his works for posterity?

Christopher Carduff: I got to know Updike professionally during the last years of his life, initially through our work together on The Golden West, a posthumous collection of Daniel Fuchs’s Hollywood stories that I assembled, in 2004, for the Boston publisher David R. Godine. Updike wrote the introduction to that book and took a strong interest in every aspect of its making, and we corresponded continuously throughout the book’s production and publication. Two years later we were again in touch when the Library of America brought out my edition of William Maxwell’s fiction, which Updike reviewed at length, and with great generosity, in The New Yorker. By that time I had joined LOA as a consulting editor, and by the spring of 2008 he and I were in conversation about his works being added to the LOA series.

Updike and I conceived two projects for LOA, a keepsake edition of his essay “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” to be published in 2010, on the fiftieth anniversary of Ted Williams’s last at-bat, and John Updike: Novels 1959–1965, which we hoped to publish in March 2012, on the occasion of his (Updike’s) eightieth birthday. Hub Fans came out as scheduled; it was the last book whose text Updike approved for publication. Novels 1959–1965 is coming out only now, nearly ten years after his death.

It was during the last few weeks of his life that we talked about future LOA Updike volumes. He laid down a handful of editorial principles that he asked me to follow. In essence, there were three of them. He asked that in every case—novels, stories, poems, essays—I reprint the latest edition of the text published during his lifetime, as he always took pains to correct his reprints. He also asked that I consult his office copies, as many of them contained autograph emendations that had yet to be made in print. And he also asked that, in the case of his novels, the contents be collected in the order in which they were published, so that the Rabbit books, previously printed in one volume as Rabbit Angstrom, would, in their LOA appearances, take their place alongside what he called “their chronological brethren.” I’ve honored these wishes while working on Novels 1959–1965.

LOA: Updike’s first novel, The Poorhouse Fair (1959), is set twenty-odd years into the future—sometime in the 1980s—and the protagonist is a ninety-four-year-old man. Did Updike deliberately set out not to write the kind of autobiographical first novel that might have been expected of a twenty-six-year-old wunderkind?

Carduff: While The Poorhouse Fair was the first novel Updike published, it wasn’t the first novel he’d completed. In 1957 he sent his then-publisher, Harper & Bros., a 600-page manuscript called Home, which was an autobiographical novel of the very sort that you allude to. It was a sprawling family chronicle about a mother, a father, and their beloved only child, and it was later a source of some of the material for The Centaur, Of the Farm, and Updike’s Olinger stories. Cass Canfield, the head of Harper & Bros., rejected the book. I suspect that, in his mind, he found it too much in the mold of, say, Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel.

Updike was insulted by this rejection, and almost immediately began work on another novel. The Poorhouse Fair was, by conscious design, everything that Home was not. It was brief, not sprawling, and was set in the near future, not the remembered past. It took as its hero a retired schoolteacher in an old-age home, not a younger version of the still-very-young author. And it was a satirical fable about the triumph of secular humanism over Christian faith, not a series of self-mythologizing episodes from one writer’s family history. Cass Canfield was bewildered by The Poorhouse Fair, and in his correspondence with Updike, he equivocated. Updike abruptly withdrew the novel from Harper, sold it to Knopf, and never looked back. Home was never published, but, as I said earlier, it was cannibalized by Updike in a dozen or more ways, in a dozen or more works.

LOA: Many readers may not be aware of the subterranean relationship between Rabbit, Run and another famous postwar American novel, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. What role did Kerouac’s book play in the genesis of Rabbit, Run?

Carduff: Updike admired the energy of Kerouac’s novel, which was published in 1957, three years before Rabbit, Run. But being at heart a Chestertonian conservative—there’s a lot of G. K. Chesterton in the thinking of The Poorhouse Fair‘s elderly protagonist—Updike was appalled by the widespread popularity of Kerouac’s antisocial message. What would happen, Updike wondered, to the American family if all the men—all the husbands and fathers—went on the road?

Rabbit, Run is, on one level, a conservative reaction to Kerouac and the Beats. Rabbit, who at twenty-six is a young father with another child on the way, certainly has the Beat impulse: he wants to get into a car and drive away from all his responsibilities, from all the relationships and expectations that would define and limit him. But his rebellion is constantly checked by the need to return, to make amends, to be a better man, to knit himself back into the social fabric. He experiences fleeting moments of God’s grace—moments of ease and mastery on the golf course, for example, or while tending the flowers in Mrs. Smith’s garden—that convince him he is capable of ease and mastery in other spheres of life. But he is worried about the state of his soul, of his being somehow outside God’s grace, of being expelled from the garden. He is prone to existential panic, and when he panics, he runs.

LOA: Updike’s late Russian translator Tatiana Kudriavtseva testified to his books’ popularity in the Soviet Union and said of Rabbit Angstrom that Updike could be “writing about the Russian man in the street.” What is it about Rabbit that people in a very different society would respond to in that way?

Carduff: The character of Rabbit seems to transcend his white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant “Americanness.” He’s a man of charisma, of a sort of roughneck, half-educated, rough-and-ready charm, who draws life and lovers to himself. He is basically good but is also deeply flawed; he lives an improvised existence full of temptations that he cannot always resist; he’s at once delightful and dangerous to know. He is forever becoming something better than he once was, and is on a path that he knows God has made expressly for him, which makes his constant backsliding so painful (and sometimes hilarious) to witness. And he does a lot of damage, to himself and to others—casually and inevitably, but without malice—as he makes his way from his middle twenties through his middle fifties and toward an early grave. He is in every way an everyman—a fair representative, I think, of the modern-male condition, wherever he is.

LOA: At first glance, 1963’s The Centaur is the most anomalous of these four books, in that we see Updike venturing beyond naturalism into allegory and myth. How was this experiment received at the time—and where do you see it slotting into the overall arc of Updike’s novelistic output?

Carduff: The Centaur is a novel with a double focus, in which the narrative advances on two tracks, in two contrasting but complementary modes. Some chapters of The Centaur are told in the third person, and concern three days in the life of George Caldwell, who is at once a high-school science teacher and, fantastically and often farcically, a centaur out of ancient Greek myth. These chapters elevate the mundane to Olympian heights, sometimes as subtly and movingly as Thornton Wilder did in The Cabala (1926), sometimes as broadly and comically as the Disney animators did in Fantasia (1940). Other chapters are told straightforwardly, in the first person, by Caldwell’s son, Peter, who is looking back nostalgically on those three days some ten years later. These are mythologizing chapters too, but the mythologizer here is the narrator, and the myth is the subjective stuff of family history. This hybrid book was widely reviewed, sold quite well, and won that year’s National Book Award in Fiction. John Cheever, who was one of the prize’s judges, wrote a citation: “In The Centaur, John Updike gives a courageous and brilliant account of a conflict in gifts between an inarticulate American father and his highly articulate son. He readily takes on the risk of flamboyance in pursuing an acuteness of feeling and introduces a cast of gods and goddesses into rural Pennsylvania.”

If The Centaur seemed eccentric to Updike’s oeuvre at the time, it doesn’t seem so in retrospect. Two of his later novels, Memories of the Ford Administration (1992) and Toward the End of Time (1997), also have a double focus. In Memories the narrator, a priapic professor of history, recalls the romantic complications of his life in 1974–77, and, in a wry counterpoint to his own story, inserts chapters from an uncompleted book he was working on during those years, a life of the sexually repressed President James Buchanan. In Toward the End of Time—a novel, like The Poorhouse Fair, set in the near future—the protagonist lives, in some chapters, in the present moment, and, in others, in a fun-house-mirror distortion of the present, a kind of waking-dream state. There’s also a good deal of the spirit of The Centaur in Updike’s novel Brazil (1994), which reimagines the legend of Tristan and Isolde in a magic-realist South American setting.

LOA: We understand that the fourth and final novel in this collection, Of the Farm, is one of your personal favorites among Updike’s works.

Carduff: You’re right, it is. It’s a brief work, more novella than novel, and has something of the perfection of the best of Updike’s short stories. It doesn’t try for much—that is, it’s modest in its ambitions—but everything it sets out to do it achieves, completely and beautifully. There are only four voices in it, an aging mother living alone in rural sandstone farmhouse and her three weekend visitors: her thirty-five-year-old son (a slick, big-city advertising man), his new, second wife (sexier, younger, less confident than the first), and his new stepson (a precocious and curious eleven-year-old). Over the course of three days, these four characters, in various combinations, test each other’s nerves, reveal their insecurities and crotchets and concerns, go to war with one another, and at last reach a four-way truce. If there is a fifth character here, it is the farmhouse, one of Updike’s settings that is so evocatively and particularly described that it takes on an almost human presence.

LOA: Is it our imagination or do these four novels seem to constitute an organic literary project on Updike’s part?

Carduff: You’re on to something. While writing The Poorhouse Fair, which is based in part on his memories of the poorhouse near his childhood home in Shillington, Pennsylvania, Updike sketched out a plan for a “Pennsylvania quartet,” a suite of four novels into which he would pour all of his impressions of his native state. Each of the novels would be set in its own time period: the near future, the present, the remembered past, and the historical past. The Poorhouse Fair, Rabbit, Run, and The Centaur conformed to this scheme, but the fourth novel, the novel of the historical past, wouldn’t gel. Updike’s chosen subject was the life of President Buchanan, and it proved recalcitrant. He would work on his Buchanan project, off and on, for more than a decade before it was published, in 1974, not as a novel but as a play, Buchanan Dying. So the scheme fell apart. Updike’s fourth published novel turned out to be Of the Farm, which is a tribute to his mother in much the same way as The Centaur was a tribute to his father.

Updike’s first four published novels hold together, very loosely, as a set. They are four buckets drawn from the same well, the seemingly bottomless well of Updike’s early impressions of life. Updike would later return to a Pennsylvania setting in his fiction, poetry, and memoirs, but seldom with the intensity that is exhibited here, in the works that established his reputation as a novelist.