“No person held to service or labour in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labour, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labour may be due.”—Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution

With this legalistic, not to say euphemistic, language America’s founders attempted to solve one of the thorniest problems confronting them in 1787: how to reconcile two societies, one slave and one free, within a single polity. But this deceptively simple injunction, known to history as the fugitive slave clause, contained within it a world of complications. Despite efforts by Congress in 1793 and again, fatefully, in 1850, to create legal mechanisms to enforce the clause, the problem posed by fugitive slaves would remain unresolved for nearly a century until the Civil War solved it in ways all the framers, northern and southern, could only have contemplated with horror.

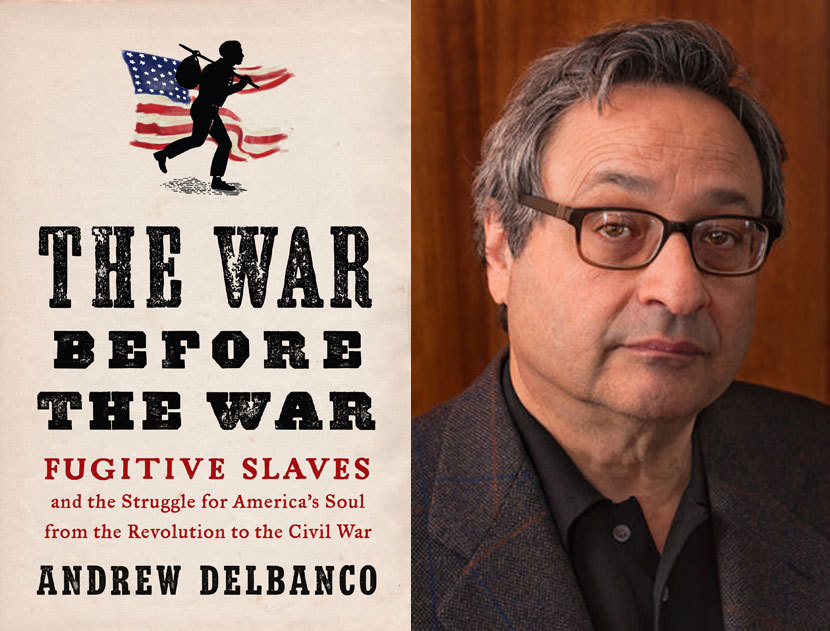

It remained so, as Andrew Delbanco shows in his powerful new book, The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War, because enslaved men and women repeatedly and persistently risked their lives to escape their bondage. In so doing, they exposed what might be called America’s founding fiction, the idea that the states were ever truly “united” in the first place.

By moving fugitive slaves to center stage, Delbanco recasts the familiar story of the coming of the Civil War, challenging our assumptions about who and what caused the Union to sunder. As much a deep meditation on the social imperatives of comity and compromise as it is a compelling historical narrative, Delbanco’s newest book is just the latest in a string of titles that has led Time to call him “America’s Best Social Critic.” Professor of American Studies at Columbia University, president of the Teagle Foundation, a nonprofit that works to support and strengthen liberal arts education, and a Library of America trustee, Delbanco took time out of his busy schedule to speak with us as his new book goes on sale.

Library of America: Spanning from the Revolution to the Civil War, The War Before the War is a history of what some scholars have called the first American republic, the constitutional regime created in Philadelphia in 1787 and sustained through a series of compromises until it was thoroughly remodeled during the Civil War and Reconstruction. You call the federal union during this period “little more than a business consortium” and argue that the fugitive slave clause was the point of the wedge that drove this precarious compact apart. What made fugitive slaves so bad for business, so to speak?

Andrew Delbanco: Just as today’s anti-immigrant fever is more about perceptions (immigrants are criminals and job-stealers) than facts (immigrants take jobs that native-born Americans won’t take), so was the struggle over fugitive slaves. By that I mean that measured by the numbers—a few thousand runaways each year, compared to several million people who remained enslaved—the whole problem, as one southern senator put it in a moment of candor, was “very small business.”

Yet every slave who dared to run for freedom posed a threat to the constitutional principle that slaves had no right to “steal themselves” from their owners in the South in pursuit of refuge in the North. Despite the relative infrequency of successful escapes, many slave owners, especially in upper-South states bordering free states, worried that their human property would flee. During the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 those fears were realized when thousands of slaves fled to British lines. In the 1830s, with the rise of the abolitionist movement, slave owners became enraged that northerners, as the British had done, were inciting slaves to run away. By the 1840s, the issue had become what John C. Calhoun called “the gravest and most vital of all questions, to us and the whole Union”—so grave that calls for secession arose throughout the South.

LOA: Historians must struggle perpetually against a certain ingrained outcome bias in themselves and their readers, the deep human tendency to view a particular period of the past through the lens of what came after. This is probably nowhere more evident in American history than in the period you tackle here, the so-called antebellum period, which has the outcome bias right there in its name. How do you try to combat that tendency here?

Delbanco: It’s impossible for anyone—not just historians—to erase from the mind our awareness of what has already happened. When we look to the past, we tend to see a chain of events—each leading to the next, as if by some iron law of necessity. We know, for example, that after Lincoln’s election in 1860, slave states seceded from the Union. We know that after the defeat of Lee’s army at Gettysburg in 1863, the tide of war turned. All such events—including the facts that the North ultimately won the war and that slavery was destroyed—now have an air of inevitability. Yet nothing was inevitable.

We know this about our own lives, but it is hard to remember it about the collective life we call history. We all feel keenly how much in our personal experience could have gone a different way if we had, say, not met the person who became our spouse, or come under the influence of a certain mentor, or stepped off the curb at the wrong moment, or given a different answer at a job interview. Such analogies may seem trivial, but there is no bigger challenge in thinking about the past than remembering that people did not know what was going to happen any more than we do. Keeping that in mind, helps, I think, to induce a certain humility in judging people who lived before us as they groped their way through the fog, trying to discern the indiscernible future. In telling the story of The War Before the War, I tried to convey the anxious uncertainty of those who lived through it.

LOA: You show how the issue of fugitive slaves galvanized public opinion in the North, especially after 1850, with particularly notorious attempts to capture runaways becoming media flashpoints, akin to police or school shootings today. And yet, as you note, with the exception of Harriet Beecher Stowe none of the now classic writers of the era treated the issue, or even the larger problem of slavery, in their fiction. Beyond a few oblique or allegorical allusions, slavery is largely missing from the works of Poe, Hawthorne, Dickinson, and Whitman. Was there a kind of self-imposed gag rule at play in the American Renaissance?

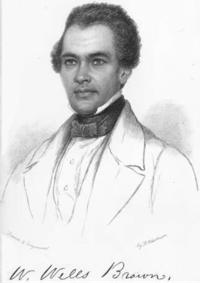

Delbanco: This is another how-should-one-judge-the-past question. I think we should check the impulse to indict the classic American writers for failing to confront slavery in a sustained way. How many of our best writers today are writing with urgent passion about the opioid epidemic, or the plight of undocumented immigrants, or the looming environmental disaster? Some, but hardly all. The fact is that writers write about subjects they know and for which their gifts are best suited. I hesitate to rank them, then or now, according to their moral alertness to any public issue, no matter how dire it might be. Among the major white writers of the mid-nineteenth century, only Herman Melville, in his great novella of 1855, “Benito Cereno,” touched the depths of slavery by telling the story of a slave revolt at sea through the eyes of a naïve Yankee ship captain who has no idea of what he is witnessing. “Slavery,” as the fugitive slave and novelist William Wells Brown told a mainly white audience in 1847, “has never been represented. Slavery can never be represented.” Melville knew that, and yet he found a way at least to suggest the depth and scope of the horror.

LOA: The story you tell touches on contested ideas of legal personhood and citizenship and on the moral imperative to assist the oppressed and welcome the stranger—much like the current cultural and political debate over immigration. How much were those parallels in your mind as you worked on this project?

Delbanco: When I began my reading and research, the issue of immigration was not yet consuming American politics. But as I continued reading and began to write, many features of the ever-changing present forced themselves into my mind: the struggle over illegal immigrants; the creation of “sanctuary cities”; the resistance of federal policy and power by the states; the collapse of the center in American politics under pressure from bitter disputes about race; and perhaps most of all, a sense of the fragility of the Republic. I did not set out to write about the past with the present in mind, but the present cannot help but inform one’s sense of the past.

LOA: We had occasion recently to speak with Yale historian Joanne Freeman about her new book, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, which, like The War Before the War, is very much about the delicate balance of principle and politics, and asked her about White House Chief of Staff John Kelly’s recent assertion that “a lack of an ability to compromise” led to the Civil War. As you observe in a footnote to your introduction, Kelly’s claim is both manifestly true and massively insufficient. And so we turn the same question to you: What has the experience of writing this book taught you about the nature of compromise in democratic government?

Delbanco: Compromise is often a morally dubious bargain. This book is in part about Americans struggling with the question of how far to tolerate an evil (slavery) in order to preserve a good (the nation). I hope that readers will come away not only with a deeper understanding of the complex choices nineteenth-century Americans faced, but also with a sense of how much easier it is to condemn people in the past than to hold ourselves to the moral standard we may feel they failed to meet.

Andrew Delbanco is the Alexander Hamilton Professor of American Studies at Columbia University, where he has been the recipient of the Great Teacher Award from the Society of Columbia Graduates. He is the author of numerous acclaimed works, including College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be; Melville: His World and Work; and The Death of Satan: How Americans Have Lost the Sense of Evil. He was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama in 2012.