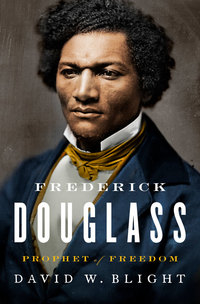

“Frederick Douglass,” James Baldwin wrote in 1948, “was first of all a man—honest within the limitations of his character and his time, quite frequently misguided, sometimes pompous, gifted but not always a hero, and no saint at all.” In the introduction to his dramatic new biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (Simon and Schuster), Yale historian David W. Blight describes Baldwin’s clear-eyed appraisal as “a good place for a biographer to begin to make judgements from the sources.” This is perhaps especially true for Douglass, since the key sources for his life are his own brilliant autobiographies, three in all, which collectively form perhaps the greatest act of self-creation in all of American literature.

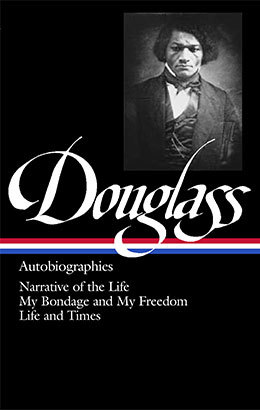

The powerful Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), published seven years after his escape from slavery, brought Douglass to the forefront of the anti-slavery movement and drew thousands, black and white, to the cause. My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), written after he had established himself as a newspaper editor, expands Douglass’s account of his slave years and describes the extent of the racial animus and segregation he confronted in the North. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, first published in 1881 and revised and enlarged in 1893, records Douglass’s efforts to keep alive the struggle for racial equality in the decades following the Civil War. (All three books are collected in Frederick Douglass: Autobiographies, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., editor, volume #68 in the Library of America series.)

Blight has been preparing for the monumental task of writing Douglass’s life for more than thirty years, establishing himself as a leading authority not only on Douglass and the Civil War era but also, more broadly, on American historical memory. This week, as the book he spent more than ten years researching and writing goes on sale, Blight took some time out to speak with us about Douglass’s extraordinary life and enduring legacy.

LOA: While there have been many biographies of Douglass, yours is the first in more than a generation, and it feels wholly new in at least a couple of ways. The first is your focus throughout on Douglass as a literary figure, on his singular gifts as an orator and writer. Indeed, in your introduction, you describe the book as “the biography of a voice.” How does this focus shape the life you tell?

Blight: Frederick Douglass was a man above all of language; he heard the music of words in his head, and fashioned them into prose that was both poetic and political. He captured the dilemma and experience of slavery and racism, the nation’s besetting sin, and the resulting crises of the Union, like few other commentators. Douglass possessed that prophet’s rare ability to say in words what people feel, aspire to, or fear. His language was sometimes very political but also at times deeply rooted in the Bible, especially the Old Testament, and therefore took on sacred qualities. He had that uncanny ability to speak in octaves just a bit above the rest of his countrymen and therefore could affect hearts and minds in unique ways.

Douglass became with time very self-conscious of being a literary figure. He wrote in nearly all genres: 1,200 pages of autobiography, thousands of short-form editorials, hundreds of highly crafted and long speeches, and one work of fiction. He even tried his hand at verse, although his best form, as he well knew, was prose poetry. Some of his orations, especially the famous Fourth of July address of 1852, among others, remain enduring classics and are today performed in public as well as widely read. We know Douglass in his words and we always will.

LOA: Like all of us, Douglass recalled his own past differently over time, his memories of his life evolving in the face of new developments, and new needs. Unlike all of us, he wrote three profoundly accomplished works of autobiography over the course of his life. What challenges do his autobiographical narratives present you as a biographer?

Blight: The first problem in writing the biography of Douglass is that the autobiographies are in the way. As a memoirist, Douglass was very cagey, even manipulative, but sometimes quite revealing. He wrote very little about his private life in the three memoirs, almost nothing about his two wives, Anna Murray Douglass and Helen Pitts Douglass. He also wrote very little about his five children, especially his three surviving sons and one daughter, with whom he was very close.

Moreover, Douglass remarks almost not at all on two other women, both European, with whom he had long and important relationships. One was Julia Griffiths, the English woman who came to America in 1849 and stayed with the Douglass family for six crucial years as she co-edited Douglass’s newspaper, becoming his fundraiser and emotional confidant during a difficult period for Douglass that included a nervous breakdown. The second woman was Otillie Assing, a German with whom Douglass had a more than twenty-year relationship of deep intellectual connection and probable intimacy.

But more important than these relationships is the simple fact that though Douglass’s autobiographies are literary classics and reveal many elements of his public life, especially the scarring nature of his slave experience in his psyche, there are countless dramas and friendships in his life that we can only wish he had uncovered more. Douglass’s autobiographies are often studied for their “accuracy,” but we should use them more for their deep and universal “truths” about both the human and the peculiarly American condition.

LOA: A second way in which your book breaks new ground is in your portrait of Douglass’s later life, a period of significant achievement and complexity that has been sometimes overshadowed by the drama and pathos of his early life and escape from slavery. How were you able to bring more detail to this crucial period?

Blight: In 2008 I first encountered the private collection of Douglass manuscripts owned by Walter O. Evans while on a lecture trip to Savannah, GA. This material had been less discovered than it was purchased over time from other collectors. The collection consists of ten or so Douglass family scrapbooks assembled largely by Douglass’s sons, Lewis, Frederick Jr., and Charles; many family letters and other documents; photographs; as well as handwritten and typescript versions of many speeches. It also contains, in particular, thousands of newspaper clippings from the final third of Douglass’s life, from the 1860s to the 1890s.

I was the first Douglass scholar to consult this collection extensively and my book is the first full biography ever to use this extraordinarily rich material. The Evans collection opened worlds we had not yet seen before: his family relationships; his back-breaking and nearly endless lecture tours into old age, including in the deep South, about which we knew almost nothing before; his personal finances revealed in the account books; his service as Marshal and later Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia; his role and place as a symbolic leader of black America; his place in the popular imagination; his hugely controversial marriage to his second wife, Helen Pitts.

Above all, the Evans collection gave me new insights into the extraordinary trajectory of Douglass’s life—the former slave born in a backwater of the South who rises to be the most famous abolitionist in America, who lives to see his cause triumphant in the Civil War, but then also lives long enough (another thirty years) to see much of that victory betrayed and eclipsed.

LOA: As you suggest, the arc of Douglass’s long life traces America’s still-unfinished struggle to achieve racial equality. What does his story have to tell us today, as our nation grapples with seemingly intractable inequities in our criminal justice, educational, and immigration systems?

Blight: Douglass delivers many legacies to us today, both from the trajectory of his life and from his ideas and writings.

He is one of the best examples ever of a person who led purely by the power of his language, a genius with words whose oratory and writing provide the primary reasons we know him. His writings, especially the autobiographies, constitute the most compelling descriptions and analysis of the nature and meaning of American slavery crafted by any American.

Douglass delivered over and over a critique of America as a slave society that had to be dismembered and destroyed before being re-created around the idea of human equality. He has a great deal to tell us eternally about what it means to be an American, and about how the issue and history of race stands at the center of that question.

On a personal level, for anyone who has ever experienced despair, captivity, oppression in any form, displacement, isolation of the soul, or legal and political denial, Douglass’s story, and his writings, offer a deep well of hope and inspiration. Douglass persevered. He might have given up many times on the struggle that defined his life, but he never did. That alone gives his life and thought lasting use and significance.

Douglass was also a pioneering activist, a creator of and believer in social protest movements. All who seek social and political change or transformation do well to examine Douglass’s example. He remains a classic model of political pragmatism borne of radicalism. His story shows us over and again that all revolutions will lead to counter-revolutions. A true reformer has to keep a long view of history and try to fashion the most effective and not always the most radical method of change.

Douglass not only lived a heroic life in his escape from slavery and the remaking of himself in freedom; he became a major thinker―about the nature of history, about the natural rights tradition, about political and constitutional philosophy, about the elements of morality in human nature.

Finally, but not least, Douglass’s world view, sense of history, and his gripping talent for storytelling rested deeply in his reading and use of the Bible, especially the Old Testament. His story reminds us that the American experience has been from the beginning infused by the power of faith, steeped in Biblical story and metaphor.

LOA: Douglass became the unlikely subject of a minor media storm last year when Donald Trump referred to him at a Black History Month event in a way that suggested the President wasn’t really familiar with who Douglass was. Besides serving as a gold mine for late-night comics, the episode raised a more serious question: what is lost when Douglass recedes from our memory, especially from the memory of those in power?

Blight: Douglass is not currently receding from our memory, quite the opposite, thankfully; but he had clearly never even been part of President Trump’s memory. That speaks volumes about the nature of the education of many people in power and it should alert us to the perils of presidential ignorance.

Douglass has become one of those figures, like Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson or perhaps Franklin Roosevelt, whom divergent groups of Americans seek to appropriate to their causes. It is always better to understand the historical person first before we adopt images or myths, although historians do not often have much control over this process.

I will say that recent claims by the Republican right that Douglass was one of them because he was a Republican and because he was an advocate of self-reliance for blacks in the nineteenth century are decidedly wrong, since they necessitate ignoring all of Douglass’s career as a radical abolitionist and a fierce critic of his country at the same time he came to love it. Douglass was a radical patriot of his own making.

When people in high places misuse history, show their embarrassing ignorance, or simply make it up to fit a particular policy initiative it is one of the highest callings of historian, journalists, and teachers to call them to task with all the reasonable weapons we possess.

David W. Blight is Class of 1954 Professor of History at Yale University, where he is also Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. He is the author of numerous acclaimed works, including Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001), which won the Bancroft, Abraham Lincoln, and Frederick Douglass prizes, and American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era (2011), which won the Abisfield-Wolf Award for the best book in non-fiction on racism and human diversity.