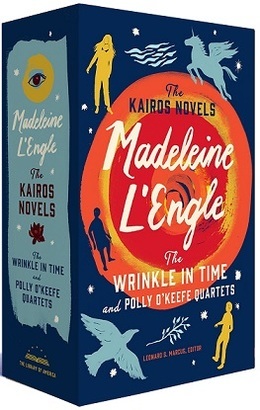

A new twentieth-century author enters the Library of America series this month with the arrival of the two-volume set Madeleine L’Engle: The Kairos Novels, which collects (for the first time) the 1962 classic A Wrinkle in Time, in a corrected text, together with all seven of its sequels. As a substantial bonus, appendices to the two volumes include never-before-seen deleted passages along with essays and addresses that shed light on the sources of L’Engle’s inspiration and demonstrate her wide-ranging intellectual curiosity.

The editor of LOA’s L’Engle edition is Leonard S. Marcus, a leading authority on children’s literature whose books include Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon, The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth, and Listening for Madeleine: A Portrait of Madeleine L’Engle in Many Voices, among others. Marcus regularly reviews children’s books for The New York Times and teaches at New York University and the School of Visual Arts in New York City. Via email, he answered our questions about Madeleine L’Engle and The Kairos Novels.

Library of America: With this new two-volume edition of The Kairos Novels, the Library of America series substantially expands its offering of children’s literature (previous entries in the series have included Louisa May Alcott’s Jo March trilogy and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, among others). What makes Madeleine L’Engle worthy of this honor? And can we speak of a “canon” of children’s literature?

Leonard S. Marcus: As someone who has written about children’s books from the dual perspective of a historian and critic for more than forty years, let me first say how thrilled I am that the Library of America includes children’s literature, and how proud I am to be playing a part in it. It represents a validation of the creative contributions of generations of writers whose aim has been to fashion work of high literary merit for young people. In the past, children’s literature, like children’s culture in general, was often relegated to second-class status. The publication of LOA’s Kairos Novels is a milestone event in the collective re-consideration of that attitude.

In addition to being an elegant stylist, L’Engle was a fearless experimenter who freely overrode genre conventions and incorporated challenging ideas from science and theology in her narratives. She had the gift, as one early reviewer noted, of “never being obvious.” In Meg, L’Engle forged a roundly human young heroine fit to stand beside Louisa May Alcott’s Jo. After Wrinkle was repeatedly attacked by would-be book-banners—sometimes for being too Christian, other times for not being Christian enough!—she also became an ardent defender of freedom of expression, eventually serving a term as the Authors Guild’s president.

From the 1930s onward, the United States produced a steady flow of literary fiction for young readers, as well as some memorable poetry. Before L’Engle, the American storytelling tradition was rooted, almost entirely, in narrative realism; after A Wrinkle in Time, the ground shifted, making a place for speculative fantasy as well. L’Engle’s generation of writers still found it necessary to argue for the seriousness of their efforts in purely literary terms. The comments of a contemporary of hers, the fantasy writer Lloyd Alexander, are typical: “On the level of high art, in their common efforts to express human truths, relationships, attitudes, and personal visions, children’s literature and adult literature meet and sometimes merge, and we wonder then whether a given work is truly for children or truly for grown-ups. The answer, of course, is: for both.”

LOA: In the introduction to your book Listening for Madeleine, you call A Wrinkle in Time L’Engle’s “most audaciously original work of fiction.” What makes it so?

Marcus: First, there is the type of story L’Engle told. Wrinkle defies categorization, melding elements of fantasy, science fiction, religious allegory, and realistic fiction. Of these four genre strands, only the last was at all prized in books for young people by the critics of L’Engle’s day. Also note the scope of the narrative: Meg’s quest is played out across the entire cosmos. L’Engle was ambitious about character, too. As a strong female protagonist, Meg had few precedents in the literature for children and teens, and she continues to be a life-altering inspiration for readers.

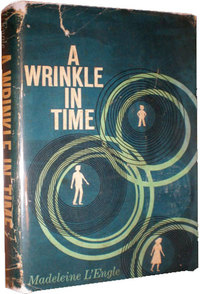

LOA: Library of America’s edition of A Wrinkle in Time presents an authoritative text restored to reflect the author’s original intentions. How is this text different from the version most people have grown up with?

Marcus: A book that has been reissued in numerous editions over more than half a century is bound at a minimum to have morphed in small, subtle ways. The LOA edition restores the text as first published in 1962, with three notable exceptions.

The exceptions: first, LOA followed L’Engle’s known preferences with regard to punctuation in every instance in which the original copyeditor is known to have overruled them. Second, LOA corrected the few minor errors that the original copyeditor missed, as in the sentence on page 19 of Wrinkle that reads: “Your father and I used to have a joke about a tesseract,” in which the second “a” was missing in the first edition. Finally, very occasional word changes introduced in later editions by unknown hands—the substitution of “jacket” for “blazer,” for example—have been turned back to the author’s original choices.

LOA: Along the same lines, our volume The Wrinkle in Time Quartet includes four passages deleted from the original book. What does the deleted material add to our understanding of L’Engle’s artistic intentions?

Marcus: From three of the four deleted passages, we learn more about Camazotz, the dystopic planet where the population lives in the thrall of the demonic controlling intelligence known as IT. We meet one character who was eliminated altogether from the published book: a blind zombie-like guide who leads Meg, her brother Charles Wallace, and Calvin on a tour of Central Central Intelligence headquarters. The fourth unpublished passage concerns Aunt Beast. L’Engle later reworked this material for the sequel A Wind in the Door. In a sense, it is the bridge between the first two books of the Wrinkle in Time Quartet.

LOA: L’Engle’s wide reading in physics is a recurring theme in the essays and addresses included as appendices to these two volumes. Where did that interest come from? Was she self-taught, or did she ever engage in formal scientific study?

Marcus: L’Engle was an indifferent science student at best and liked to say that “higher” mathematics suited her better than the “lower” kinds such as multiplication and long division. But she was a quester by nature and turned to books about astrophysics and molecular biology as well as theology in search of a unified theory of what she called the “real reality.” Although she was known for her longtime association with the Episcopal Church and took great pride in her role as writer in residence at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine, L’Engle always left the door ajar for doubt. She kept a porcelain Buddha on her cathedral library desk as a reminder that no one group had all the answers.

LOA: Readers coming to Library of America’s new L’Engle edition may know A Wrinkle in Time but not the seven later novels. If that’s the case, what have they been missing?

Marcus: L’Engle was first and foremost a superb and adventurous storyteller. Her father, Charles Wadsworth Camp, was a mystery writer, and she too felt drawn to the genre, as may be seen in The Arm of the Starfish, Dragons in the Waters, and House Like a Lotus. Her love of travel is in evidence in these three novels of “international intrigue,” as she called them, whose settings range across Europe and South America. In Many Waters, L’Engle ventured in a different direction, re-imagining a pivotal episode from the Old Testament, the story of Noah and the flood. And in A Swiftly Tilting Planet, she flipped the cosmic expansiveness of Wrinkle by constructing a micro-verse like the one depicted a few years earlier in the science fiction film (and subsequent novelization by Isaac Asimov) Fantastic Voyage. Taken together, L’Engle’s eight Kairos Novels, written over a period of more than twenty-five years, come together as the family saga of the Murrys and O’Keefes across three generations.