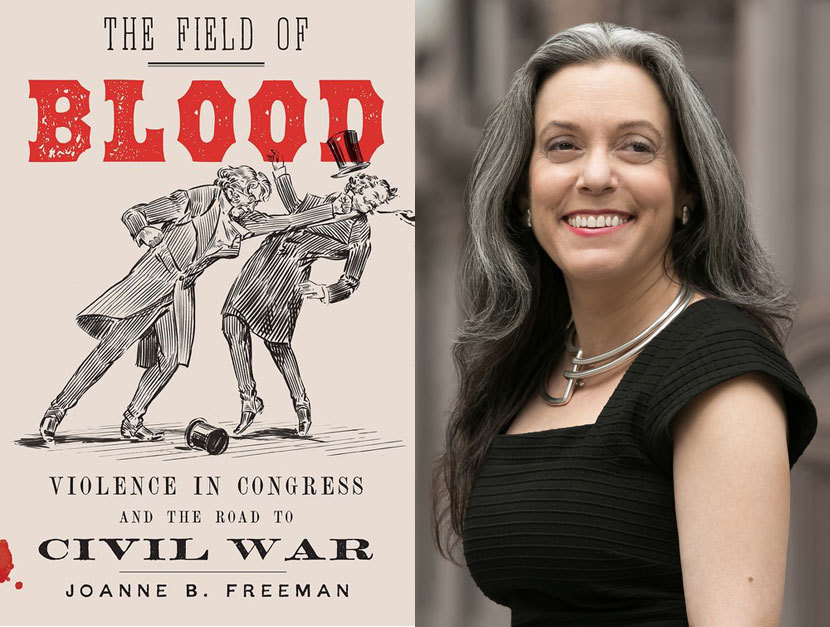

Joanne B. Freeman recovers the surprising story of congressional violence in the antebellum era

More than a few pundits have looked at our current political era of hyper-polarization and degraded discourse and wondered, have affairs in Washington ever been so bad? In her new book, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, the product of more than fifteen years of research and writing, historian Joanne B. Freeman answers with an emphatic yes—and then some.

Documenting roughly seventy separate instances, Freeman exposes a shocking record of physical violence in Congress in the three decades before the Civil War, one that has remained largely hidden from view until now. Here are congressmen throwing punches, overturning chairs, brandishing guns and knives, initiating and accepting duels, and joining in all-out brawls. As Freeman shows, violence—both the ever-present threat of it, and the actual fact of it—was a core part of the political process in the nineteenth century Congress, employed by politicians who wished to push their interests or cow their opponents, especially on the crucial issue of slavery. In a very real sense, as she shows, the first battles of the Civil War were fought inside the United States Capitol.

Best known as one of the world’s leading experts on Alexander Hamilton (the edition of Hamilton’s writings that she edited for Library of America was an inspiration to Lin-Manuel Miranda as he was writing his musical, and she is a historical consultant on the new traveling Hamilton exhibition, which opens at Northerly Island in Chicago in April), Freeman is the author of the award-winning history Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (2001), which examines the volatile political culture of the early republic. A Library of America trustee, Freeman was kind enough to take some time this week to answer a few questions about her new book as it goes on sale.

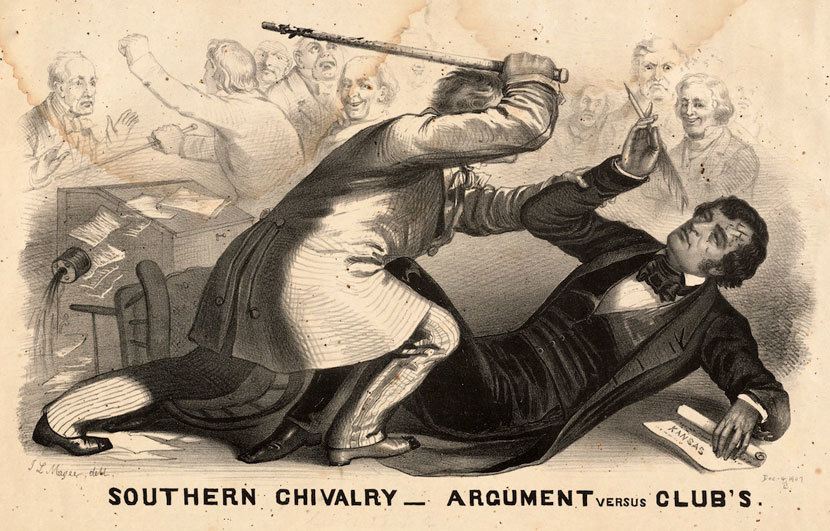

Library of America: While many readers may have heard of the vicious caning of Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner by South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks on the Senate floor in 1856, the scale and frequency of violence in and around the Capitol described in The Field of Blood will come as a revelation. How did you first get the idea for this project?

Joanne B. Freeman: The short answer is: I found intriguing evidence. Casting about for a new project after completing Affairs of Honor, I decided to explore manuscript collections of politicians a few decades after the period covered in my first book in the hope of seeing how politics, honor culture, and violence changed (or didn’t change) over time. I started by reading the papers of a congressman whose colleague was killed in a duel. As luck would have it, he wrote to his wife almost every day, and as I began reading, I kept coming across near-fights and physical confrontations. Congressmen threatening each other. Punching each other or pushing up their sleeves to throw a punch. It was surprising, so I began to test boundaries, reading the papers of other congressmen from that period. In the three months that I spent researching in congressional papers at the Library of Congress, I never opened a collection without finding at least one violent threat or physical clash. Clearly, here was a story waiting to be told.

LOA: A key part of the story here is the role of newspapers, both the party organs which functioned as the Congressional Record of their day and the independent press that developed with the advent of the telegraph. How did the ways they chose to cover, or conceal, congressional violence affect your research?

Freeman: It had an enormous impact on my research and ultimately on the book’s argument. The story of congressional violence hasn’t been told, in part, because it’s hard to find. You have to know to look for it, you need to dig to find it, and a lot of what you’re seeking isn’t there.

For a time, the insular Washington press community didn’t report much of the violence, only noting the occasional argument or “sensation.” Part of the reason for this was economic; printing contracts could make or break a newspaper, and Congress did the granting, so congressmen had some control over their spin. As a result, within the record, many of the sharp edges of violence and intimidation are smoothed away. The folks back home could see their representatives defending their rights with gusto on the floor, but more often than not, without crude language or physical force. When guns were pulled, they usually weren’t mentioned. When congressmen began threatening each other with duel challenges or violence, the debate often was said to have become “unpleasantly personal.” Massive brawls couldn’t be masked. But a lot of fighting and intimidation could be prettified or omitted entirely. Some fights are only visible in the record because the fighters negotiated an apology and wanted it announced on the floor to protect their reputations.

The rise of an independent press changed these dynamics. These reporters and editors could say what they liked—and they did; by the early 1850s, the telegraph was spreading news of congressional mayhem throughout the country with ever increasing reach and speed. The political climate was also becoming angrier and more polarized because of the rising immediacy of the polarizing problem of slavery. So not only was there more fighting, but it appeared more frequently in the press, though even then it was reported selectively. Or invented entirely. In the case of a few fights that I found in newspapers, I still don’t know if they happened. Finding and piecing together congressional clashes required a lot of triangulation between diaries and correspondence, the congressional record, and newspaper databases. An appendix in the book discusses this detective work in more detail.

LOA: If only we’d had C-SPAN! The 1838 duel between Maine Democrat Jonathan Cilley and Kentucky Whig William J. Graves, the only instance of one congressman killing another in our nation’s history, figures prominently in your book, a fatal exception to the largely non-lethal Southern strategy of deploying the honor code to bully their opponents and silence debate. Among other things, the episode reveals the extent to which Northerners and Southerners seemed to be working off different cultural playbooks when they convened in the nation’s capital. Why was this Southern strategy so successful?

Freeman: In addition to the apportionment advantage that Southerners had in Congress due to the Constitutional Convention’s Three-Fifths Compromise (which counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of representation and taxation), Southern congressmen had a cultural advantage, a product of the realities of a slave regime. A system of slavery relies on intimidation, threats, and violence; leaders are expected to have those qualities. Northern society was violent, but not in the same way, and northern congressmen knew that their constituents would disapprove of their representatives fighting duels or waving Bowie knives. Southerners routinely used this difference to their advantage in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, intimidating Northerners into silence or compliance with threats, weapons, and duel challenges. These “rules of force” served Southerners well until the sectional crisis of the 1850s pushed many Northerners to want their representatives to literally fight for their rights.

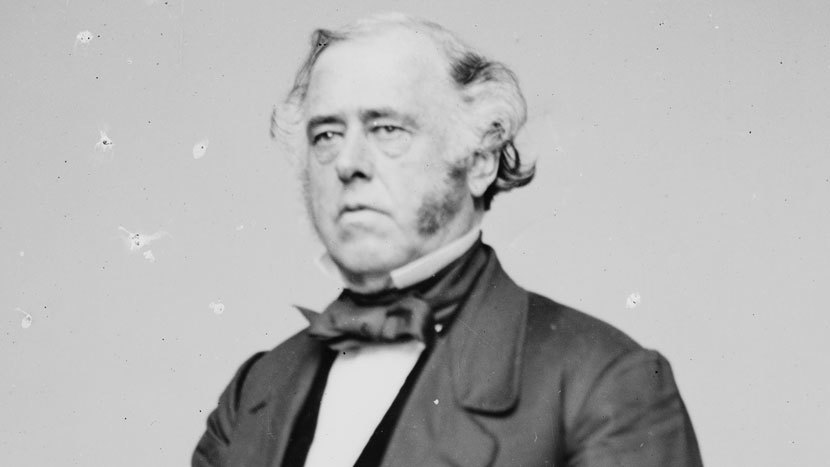

LOA: Longtime House clerk Benjamin Brown French, whose eleven-volume diary is a key source for you, seems to have been present for an astonishing number of historically significant episodes. Though he was not himself a shaper of events, what does his perspective add to the story you tell?

Freeman: I’ve come to think of French as a nineteenth-century Zelig, on site when history unfolds, but rarely playing a central role. So he certainly revealed much about some of the better known people and events in The Field of Blood. As a clerk whose job entailed watching and recording congressional proceedings, he was an invaluable eyewitness to congressional violence. Perhaps most valuable of all, French offers a ground-level view of what it felt like to see one’s nation torn in two. A dedicated “doughface” Democrat in the 1830s, willing to do anything to appease the South, promote his party, and preserve the Union, by 1860, he was armed and ready to shoot Southerners. His emotional transition over the course of the book offers invaluable insight into the emotional logic of disunion; it reveals the gradual process by which Americans learned to turn on each other.

LOA: Another invaluable source for unearthing or corroborating episodes of violence is John Quincy Adams’s diary (recently published in a two-volume selected edition by Library of America.) Adams’s extraordinary congressional career was distinguished by his long, ultimately successful campaign against the so-called Gag Rule, which prohibited debate on slavery. Why was Adams such an effective adversary of the Slave Power, as it came to be known?

Freeman: Adams was a remarkably effective anti-slavery advocate in Congress for a number of reasons. First and foremost, his lifetime in politics had taught him a lot about political strategizing, and his mastery of parliamentary etiquette enabled him to manage, maneuver, and sometimes force his way into debates; there was no better man for challenging the constitutionality of gag rules. He also had the character for the campaign. To quote Ralph Waldo Emerson, Adams was a “bruiser” who “loves the melee”—which he assuredly did. At least once, he deliberately pushed the House into chaos and then quickly dropped into his seat, at which the chaos immediately stopped, leaving him convulsed in laughter. Last and equally important was his near invulnerability as a target of violence. Elderly (sixty-three years old when he entered the House), a former president of the United States, and the son of a president who was also one of the nation’s foremost Founders, Adams was beyond assault, a fact that he used to full advantage, attacking gag rules with a savagery that would have earned other men blows. (His fellow antislavery advocate Joshua Giddings of Ohio was assaulted at least seven times.)

All of this and more is readily apparent in Adams’s diary, which I can’t resist praising; a descriptive, animated, wry, personal account of his congressional career, it’s hard to match as a source of knowledge about the raw reality of the antebellum Congress.

LOA: White House chief of staff John Kelly stirred considerable controversy when he suggested recently that “the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War.” What has the experience of writing this book taught you about the nature of compromise in democratic government? Are there lessons here as we confront the major moral issues of our own time?

Freeman: Writing this book drove home a core emotional truth at the heart of our political system: the importance of trust in republican governance. In antebellum America, people didn’t take the existence of the Union for granted or assume that it was an unbreakable structure of government. They knew that a republican form of governance was grounded on equal membership, a sense of fundamental fairness, and mutual trust between its members. For a republic to survive, its citizens need to know that the political game is being played on an even playing field, and that everyone has an equal chance to fulfill their demands, needs, or rights. When this isn’t true—when people feel that the political game is rigged or that their opponents have an unfair advantage—the core of republican governance begins to erode. People of opposing views begin to distrust each other, and without at least some degree of mutual trust, the core process of debate and compromise collapses; the American people lose faith in national governance; and our political system can’t function. That’s why a solid, sturdy process of governance, documented in a constitution, is so important. It sets the ground rules.

At our current moment of crisis, rules and norms are being violated on all sides, and distrust between the left and right is running rampant. A commitment to our core process of governance offers a way out of the crisis, because it opens up—at a bare minimum—a field of debate. The continued flouting of political rules and norms—and the mounting distrust that it is causing—will continue to erode what I refer to in my book as the “national we.”

Joanne B. Freeman is professor of history and American Studies at Yale University, and the author of the award-winning Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic. She is a trustee of the Library of America, for whom she has edited Alexander Hamilton: Writings and The Essential Hamilton. She is also a cohost of the popular history podcast BackStory.