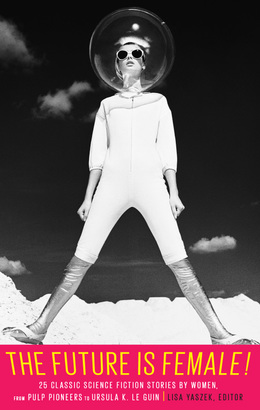

Out this fall from Library of America, The Future Is Female! 25 Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women, from Pulp Pioneers to Ursula K. Le Guin is a groundbreaking anthology—the most comprehensive of its kind—of women writers in American science fiction. Editor Lisa Yaszek has selected the best of this tradition, by recognized masters as well as lesser-known names who are overdue for rediscovery.

Imagining strange worlds and unexpected futures, gender-bending aliens, interplanetary battles of the sexes, and much more, these provocative stories demonstrate that women writers created and shaped speculative fiction as surely as their male counterparts. Taken together, they form a thrilling journey of literary recovery and a bracing challenge to conventional accounts of the genre.

Lisa Yaszek is Professor of Science Fiction in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech and past president of the Science Fiction Research Association. She is the author of Galactic Suburbia: Recovering Women’s Science Fiction (2008), and coeditor of Sisters of Tomorrow: The First Women of Science Fiction (2016). Via email, Yaszek answered our questions about The Future Is Female! just prior to its publication.

Library of America: The Future Is Female! collects twenty-five stories published between 1928 and 1969. How much material did you read through before you made your final selection, and did you have any specific criteria in mind when you started?

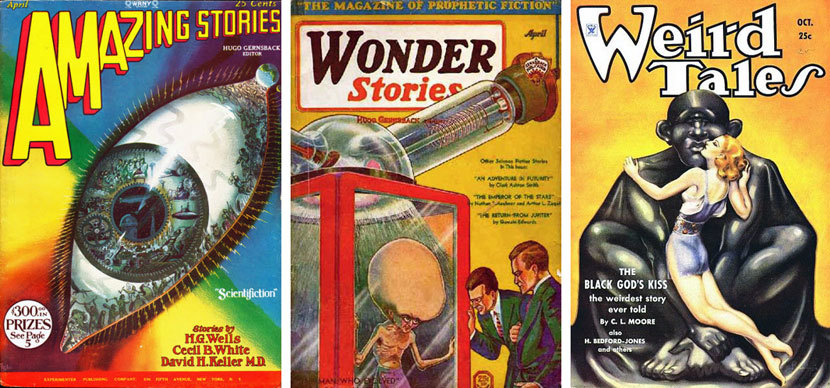

Lisa Yaszek: I read a lot of stories for The Future is Female! To give a sense of scope: nearly 300 women entered the science fiction community between 1926 and 1940; about 300 more made their own contributions in 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. I wanted to honor these genre pioneers by considering at least one story from all of them (and often many more); to put together an anthology that included both classics by science fiction luminaries and stories by women who were celebrated in their own time but then lost to history.

Two interlocking set of criteria guided my reading and selection process. I wanted to showcase the diverse ways that women have contributed to the development of science fiction as the premiere story form of technoscientific modernity, especially as that story form developed in the United States in the early to mid-twentieth century. From the very beginning, women wrote stories that grappled with everything from theories of evolution and the mechanics of space travel to the perils of nuclear war and the promises of connecting with alien others. They also—and often at the same time—asked readers to think about the necessary relations of science, technology, and gender while putting women at the center of humanity’s many possible futures. I wanted readers to see that even as science fiction writing has evolved radically over the years, the issues that women explored in the first and middle parts of the twentieth century are very much still with us today.

I also wanted to showcase the aesthetic space where these women experiment with a range of literary techniques to best capture human reactions to scientific and social change. For instance, from the very beginning, women writers have evinced a great deal of interest in character development and the interiority of their literary creations—in some ways, it’s a short, straight path between Clare Winger Harris’s 1928 story “The Miracle of the Lily” and, say, Sonya Dorman’s 1966 tale “When I Was Miss Dow”: both illustrate the internal struggles of rational, intelligent beings who are confronted with what seems the impossibly biologically alien other.

Indeed, even as they cast themselves as the sheroes of tomorrow, women writers were willing to depict their literary selves as complex and even flawed beings who had complex and sometimes imperfect reactions to the world around them—C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry is a brave warrior queen whose judgement is muddied by pride; Alice Eleanor Jones’s unhappy housewife heroine lends her children to sterile women in return for the little luxury items she needs to make post-apocalyptic life bearable; even Joanna Russ’s Alyx is pleased to profit from her relationship with an unscrupulous wizard until it no longer suits her. All of these authors do more than simply deploy stereotypical images of women to make larger points about future scientific or social relations; rather, they invite readers to sympathize with their characters’ perspectives, to imagine what it might feel like to actively live through those relations as they could evolve over time.

LOA: Some of these stories, like Judith Merril’s “That Only a Mother” and Kate Wilhelm’s “Baby, You Were Great,” still have a noteworthy power to shock decades later. What do we know about how they were originally received—did they stir up controversy among the fan community, or editors, or other writers, for instance?

Yaszek: Many great works of fiction have great origin stories behind them, and Merril and Wilhelm’s tales are no exception. Both of these stories are particularly noteworthy because they were inspired by specific conversations within the science fiction community. Merril’s story—which inaugurated the subgenre of domestic science fiction and introduced genre readers to the character of the housewife heroine—was the product of an argument that Merril had with Astounding Science Fiction editor John W. Campbell. Campbell was part of a small but influential group of second-generation science fiction editors who picked up the rhetoric of feminist backlash that swept the nation in the 1930s and ’40s and claimed that (despite their publication track record!) women couldn’t really write science fiction. When Campbell announced his feelings on the subject at a convention, Merril told him she would write a story that was so good he would buy it and beg her for more. And that’s pretty much exactly what happened: Merril sent Campbell “That Only a Mother,” he published it, and asked her for more. But Merril was almost a victim of her own success. When she sent Campbell her next story—a Mars colonization story—he rejected it because it didn’t center on housewives. Fortunately, other editors were more open-minded on the subject of what women could and should write, and so Merril’s career flourished.

The story behind Wilhelm’s story is less dramatic but equally interesting. Wilhelm wrote “Baby, You Were Great” in reaction to a 1964 short story called “Semper Fi” by her husband Damon Knight, who was a well-known genre author in his own right. Wilhelm appreciated Knight’s exploration of what we would now call virtual reality and how it might enable us to live out our fantasies but disagreed with his conclusion that if we could manipulate dreams, they would remain a private affair. Instead, as she put it in her introduction to the story for [the collection] Better Than One, “in [my story], if dreams can be controlled, they will be.” In short, Wilhelm decided to rewrite “Semper Fi” with a different—and decidedly darker—plot, setting, and cast of characters.

The origin story for Wilhelm’s work also gives us a perhaps even more interesting look at a standard science fiction practice. From early on, science fiction writers participated in the conversation around science in society by invoking and revising each other’s stories. And that is, of course, exactly what Wilhelm was doing in the privacy of her own home and then the public sphere of literary production—invoking and revising her husband’s story!

While Merril and Wilhelm’s are great tales that give us insight into the politics and aesthetics of early science fiction authors and editors, other stories did indeed shock fans. At the height of her considerable popularity, Leslie F. Stone published “The Conquest of Gola,” a battle of the sexes story that required readers—who were likely to be human men—to side with a female alien narrator as she and her sisters fend off attack by males from Earth. As Stone dryly recalled four decades later, readers who had always supported her writing were suddenly up in arms because “male chauvinism just couldn’t take that.” In a similar vein, Leslie Perri’s 1941 short story “Space Episode”—the tale of a female astronaut who sacrifices her life when her male colleagues are too paralyzed by fear to save their ship—caused celebration among women readers who recognized this dynamic in their own lives and grumbling amongst male readers who dismissed the story as “sour grapes.”

What’s particularly interesting about these two incidents is that they seem to have been resolved reasonably well in the letters pages of the respective magazines in which they were published, with editors moderating the conversation and authors throwing in their own two cents. By the 1960s, however, editors seem to have become more interested in heading off controversy before it could even begin. Juanita Coulson, who co-authored the male pregnancy story “Another Rib” with Marion Zimmer Bradley, recalls that editors asked her to use the male pseudonym John J. Wells to mitigate what they thought would be readers’ shock over the story; similarly, when Ursula K. Le Guin sold “Nine Lives” to Playboy (another first for women in science fiction!), she was asked to use the byline U. K. Le Guin for much the same reason. I suspect the difference has to do with the changing status of science fiction over the years, as it shifted from a disreputable and somewhat minor genre that was closely tied to a fan base that prided itself on its argumentative nature to a major genre with a relatively wide appeal that editors wanted to capitalize upon and expand. Even so, it’s hard for me to imagine that readers would have been any less shocked by these stories if they thought they were written by men. . . or aliens!

LOA: In the course of preparing the collection, and reading (or re-reading) so much science fiction by women, did you encounter any surprises?

Yaszek: Yes, as I read and re-read all the marvelous (and mediocre, and even terrible) stories that women wrote for the science fiction magazines of the early and mid-twentieth century, I was surprised at how thoroughly wrong we tend to get it when we talk about the history of women in the genre! One of the most common stories you hear about gender and science fiction is that while Mary Shelley is a founding figure in science fiction, other women didn’t really participate in the genre until the revival of feminism and the advent of a distinctly feminist science fiction in the 1960s and ’70s. But as my own and other authors’ research shows, that story just isn’t true! Women have been part of the modern science fiction community since the first magazines were published in the 1920s, comprising about 15% of all authors (that number doubled in the 1970s and remains about 30% today). Moreover, as we see in this anthology, they wrote about the same range of topics as their male counterparts—space exploration, alien encounters, human-machine relations—while showing how seemingly mundane spaces like the home and the classroom could also be sites of technoscientific action and adventure.

The fact that these were women writing all this science fiction was both well known and, for the most part, welcome. We tend to assume that if and when women wrote science fiction before the 1970s, they defaulted to masculine or androgynous pen names to sell their stories to male editors and readers. But of course, as any modern science fiction writer worth her salt will tell you, all genre authors use pen names at times, so they don’t flood the market—and as I learned while researching this book, sometimes men used female pen names! Even more importantly, most women didn’t use masculine pen names. They published as women, and, at least in the early days, editors often published pictures of authors along with their stories, so it should have been clear that, say, Leslie F. Stone was indeed a woman. Additionally, when readers mistook the gender of an author, editors were quick to correct them. Many of those early editors were excited to have women write science fiction. It proved the popularity and importance of this brave new genre—it was so important that even schoolgirls and housewives wanted to write it.

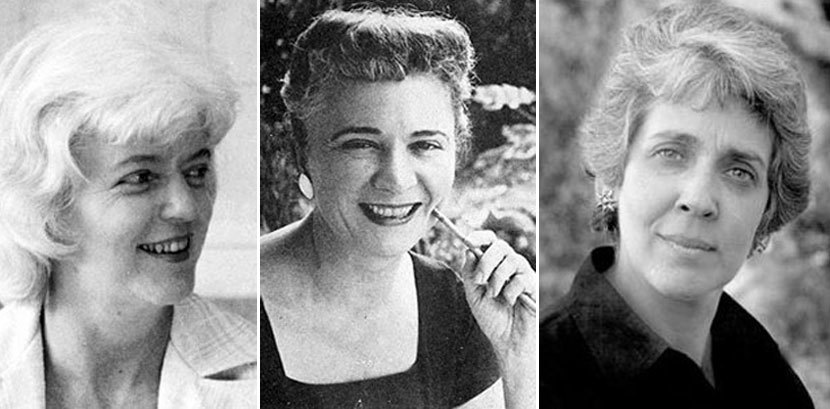

The last thing that surprised me was that while there were indeed one or two famous cases of women writers passing as men in each generation, most of those women made that choice for reasons that had little or nothing to do with the science fiction community. Pioneering science fiction and fantasy author Catherine L. Moore became C. L. Moore in the 1930s so she wouldn’t lose her day job at a bank (something that happened frequently to both men and women with secondary incomes during the Great Depression). Mary Alice Norton became Andre Norton in the 1940s when she launched a career as a boys’ adventure writer, and simply brought that established name with her when she began publishing science fiction (even though she had already been working in science fiction as an editor and everyone knew she was a woman).

Finally, Alice Sheldon took the pen name James Tiptree, Jr. to protect her career as a former CIA agent and budding psychologist. What we learn from these stories is that when women took on male and androgynous pseudonyms, they did so in reaction to larger discriminatory forces in the United States, rather than specifically in reaction to the science fiction community itself.

LOA: Two formidable female protagonists happily encountered in these pages—C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry (“The Black God’s Kiss,” 1934) and Joanna Russ’s Alyx (“The Barbarian,” 1968)—bring to mind last year’s big-screen blockbuster Wonder Woman. Is mainstream popular culture finally catching up with these kinds of characters?

Yaszek: I certainly hope so! Of course, it’s important to note that Wonder Woman first appeared in DC Comics in 1941, so she and Jirel of Joiry are actually contemporaries, both inspired by the accomplishments of first-wave feminists who fought for equal political rights. For instance, we might well note that both Jirel and Diana are royal women who buck gendered human social convention. They are “sheroes”: women with strength, intelligence, and moral codes that equal or exceed those of any men, but who specifically champion women, diversity, and/or social justice. Alyx is a marvelous updating of Jirel and Diana. She is every bit as strong , intelligent, and moral as her literary predecessors, but also more approachable and more human—she is not impossibly young, beautiful, and virginal, but middle-aged, grappling with a changing body, and comfortably married. If Jirel is, as C. L. Moore once said, the fantastic projection of the self she wanted to be, Alyx is the equally fantastic representation of what all women already are in the here and now.

Having said all this, yes—the sheroes of print science fiction certainly seem to have anticipated and perhaps even inspired many of the fantastic blockbuster heroines who have graced the silver screen over the past few decades. The 1970s gave us Princess Leia, the first science fiction film heroine to pick up a gun and save herself from the bad guys when she realized that the men around her couldn’t do it, and Ellen Ripley, the first science fiction heroine to pick up a gun and save herself from an alien threat unleashed by corporate greed when her colleagues are all killed. This may have been first time mainstream audiences met science fiction sheroes, but as noted above, they were not first of their kind! Lida, the astronaut protagonist of Leslie Perri’s “Space Episode,” realizes she can’t wait for her male comrades to save them from certain death in space, so she picks up a wrench and takes care of business herself, even though it means her own life. As such, she anticipates both the impatience and resourcefulness that we see later in Princess Leia. We can find similar resonances between Ellen Ripley and Steena of Andrew North (Andre Norton’s) “All Cats Are Grey”—both women are relatively invisible participants in the endeavor of space exploration until an alien threat that men can’t defeat leads them to become the heroines of their own life tales. I hope that readers will find other strange and fruitful connections between early print science fiction and its Hollywood counterparts!

LOA: The theme of gender identity becomes strikingly prominent once the collection reaches the 1960s, for instance in the stories by Sonya Dorman and Marion Zimmer Bradley. What had changed? Is it fair to say the earlier stories in the book feature more traditional (i.e., conventional) gender roles while the later ones lean toward something more like feminism?

Yaszek: Like science fiction, feminism is a big tent. In this case, it’s a tent that includes diverse ideas about and approaches to issue of sex and gender equity. So I’d say that it’s most accurate to think of this collection as offering readers a window into the history of feminist ideas and concerns as they have changed over time. For instance, early science fiction stories such as Leslie F. Stone’s “The Conquest of Gola,” C. L. Moore’s “The Black God’s Kiss,” and Leslie Perri’s “Space Episode” dramatize first-wave feminist ideas about women’s participation in the public sphere. In fact, they all use the story form we call “the battle of the sexes” to specifically disrupt conventional ideas about men as action heroes and women as passive love interests and damsels-in-distress.

While midcentury authors such as Andrew North (Andre Norton) continued to write stories about strong, heroic women, many stories from the 1940s and ’50s seem to back off from progressive politics and embrace new postwar ideas about women as “domestic patriots” who best serve themselves, their families, and their countries as wives and mothers. And it is true that authors including Zenna Henderson, Wilmar H. Shiras, Judith Merril, Alice Eleanor Jones, and Rosel George Brown made their names writing domestic science fiction stories centered on what feminist author Betty Friedan called “the housewife heroine” character who dominated midcentury popular culture. Even Leigh Brackett—who made her name in the 1940s writing interplanetary romances and hard-boiled detective fiction—tried her hand at this story form with “All the Colors of the Rainbow.”

But it’s important to look carefully at just how women writing science fiction use these characters: more often than not, these incredibly conventional, even conservative characters challenge midcentury America’s most dearly held beliefs about the necessary relations of science and society. Merril and Jones use their unhappy housewife heroines to critique the status quo of Cold War social and sexual relations, Henderson and Shiras use the feminine space of the classroom to explore the impact of cold war conformity on the American imagination, and Brackett uses the tragic adventures of a young married alien couple to make a rather sharp critique of American racism. Even Brown’s preschool carpool comedy carries with it serious messages about xenophobia, class tension, and the importance of women working together to secure new and better futures for all.

While this kind of reproductive futurism might seem suspect to us in the modern moment because it flattens the diversity of gender and links futurity to normative heterosexuality, it was absolutely central to women’s work in the midcentury pro-peace and civil rights movements. And so once again, these stories might not look like modern feminist stories such as The Handmaid’s Tale or A Wrinkle in Time, but they very much dramatized and engaged the ideas of midcentury progressive people.

The 1960s and ’70s saw a revival of feminism across the globe. In the U.S., much feminist activity centered on issues we are still debating today—ensuring equal access to education and employment, rethinking women’s relations to science and technology, considering the diverse experiences of women across race and class lines, exploring how much of sex and gender is nature and how much is culture. So it’s no surprise that stories addressing these issues feel modern and relevant, even if they are fifty years old! As you note, Dorman’s “When I Was Miss Dow,” Bradley’s “Another Rib,” and, I would add, Le Guin’s “Nine Lives,” all complicate our ideas about sex and gender as universal categories. Others, such as Doris Pitkin Buck’s “Birth of a Gardener,” Russ’s “The Barbarian,” and James Tiptree, Jr.’s “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain,” expose the patriarchal and masculinist underpinnings of modern science and technology. And still others—especially Kit Reed’s “The New You” and Kate Wilhelm’s “Baby, You Were Great”—demonstrate how women might be further oppressed, rather than liberated, by new media technologies. Such stories are more relevant than ever in an era marked by debates over gender inclusivity, STEM education, and the meaning and value of social media and the virtual lives we conduct therein.

LOA: Of the twenty-five stories, could you name a favorite? Are there particular stories you would recommend to students or friends who haven’t read much science fiction before?

Yaszek: Asking a literary scholar to pick her favorite story is like asking a parent to pick its favorite child—a terrible, terribly interesting, and totally unfair question, the answer to which changes day to day.

Right now I would recommend that novice readers begin with these three stories: C. L. Moore’s “The Black God’s Kiss,” Alice Eleanor Jones’s “Created He Them,” and Sonya Dorman’s “When I Was Miss Dow.” Each of these stories is an excellent representative of the thematic concerns and literary techniques that women have deployed over the course of the twentieth century as they crafted fiction that both helped build their chosen genre and enabled them to express their hopes and fears about what it might mean to be a modern woman of the world. They offer us rich, complex depictions of their protagonists—all of the protagonists in these stories are smart, strong, and clever, but each is also vulnerable and flawed. Readers can both relate to and be inspired by such characters. And that’s what science fiction does at its very best: it offers us fresh perspectives on our world, our relation to science and technology, and to ourselves.

A companion website to The Future Is Female! explores the origins and evolution of women’s science fiction in America with author biographies, original illustrations and jacket art, film and video clips, and exclusive commentary.