As Summer 2018 winds down, we’ve asked our two summer interns to share something they learned during their time with Library of America. Below, Ashley Leader, a senior at Pomona College who is majoring in English, describes her discovery of the novelist Ann Petry (1908–1997), who enters the LOA series in February 2019.

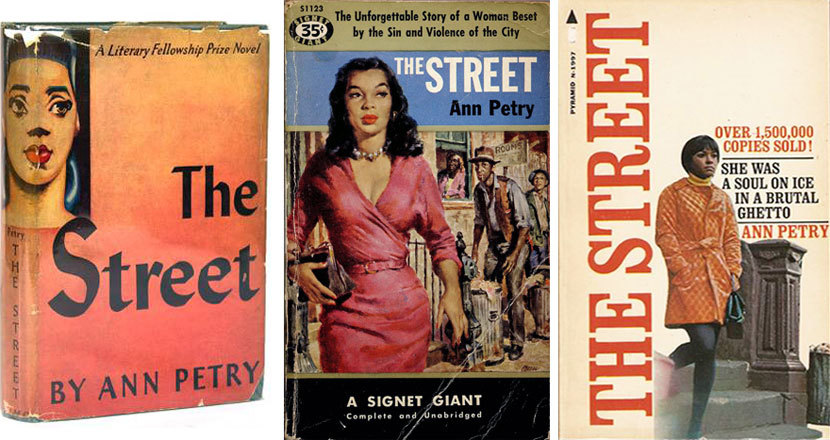

Ann Petry’s 1946 novel The Street is a difficult book to recommend. Not because I have doubts about its worth—quite the opposite. It was the first novel by an African American woman to sell over a million copies, proving that there was a market out there hungry for black women’s voices. But before I get to the meat of this post, which is trying to convince you to take a look at this often-overlooked novel, I feel I should warn you: it’s not exactly what I’d call a fun read. That’s not to say it’s difficult stylistically or overly intellectual or anything—Petry’s writing is refreshingly approachable—but it is genuinely heart-wrenching.

The Street is not about a woman who makes a series of bad decisions resulting in her ultimate downfall. It’s about a woman, Lutie, who makes good decisions, or at least the best ones possible in her circumstances, but who is already trapped. This becomes clear as Petry fleshes out the various nefarious characters who inhabit “the street,” the block on 116th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues in Harlem. No amount of strong morals, good decision-making, or Puritan work ethic—all of which Lutie possesses in abundance—could extricate her from the network of exploitation surrounding her. Her extraordinary beauty serves not to help her rise in society, but acts only as a lure to attract predators.

As a black woman living in America during World War II and dependent on white people for an income, Lutie is constantly being silenced. While working as a maid for an affluent white family, Lutie must pretend not to hear her employer’s friends say they would never hire a pretty black woman to work anywhere near their husbands, the implication being that black women must be eager to sleep with white men. Lutie cannot, of course, point out that she is both married and uninterested in white men. She must keep her job, since her husband, as a black man, has a harder time finding work than she, and they have a young son to support.

Lutie is not only beautiful, but also a talented singer, as we learn in one of the novel’s most evocative passages:

She moved the beer glass on the bar. It left a wet ring and she moved it again in an effort to superimpose the rings on each other. It was warm in the Junto, the lights were soft, and the music coming from the juke-box was sweet. She listened intently to the record. It was “Darlin’,” and when the voice on the record stopped she started singing: “There’s no sun, Darlin’. There’s no fun, Darlin’.”

The men and the women crowded at the bar stopped drinking to look at her. Her voice had a thin thread of sadness running through it that made the song important, that made it tell a story that wasn’t in the words—a story of despair, of loneliness, of frustration. It was a story that all of them knew by heart and had always known because they had learned it soon after they were born and would go on adding to it until the day they died.

Just before the record ended, her voice stopped on a note so low and so long sustained that it was impossible to tell where it left off. There was a moment’s silence around the bar, and then glasses were raised, the bartenders started making change, and opening long-necked bottles, conversations were resumed.

Lutie has not been asked to sing, and she receives no rewards. She sings simply to give voice to her sorrow and to the sorrow of others. Subsequently, Lutie attempts to make a career out of singing, but the men she imagines will improve her life by hiring her know that she is more vulnerable without money, so they instead attempt to manipulate her. When Lutie auditions for a singing gig at a casino, she feels viscerally that her voice is being taken from her:

As she held the mike, she felt as though her voice was draining away down through the slender metal rod, and the idea frightened her.

As Lutie’s circumstances darken, her voice turns from singing to crying. Her neighbors pretend not to hear:

All through the house radios went on full blast in order to drown out this familiar, frightening, unbearable sound. But even under the radios they could hear it, for they had started crying with her when the sound first assailed their ears. And now it had become a perpetual weeping that flowed through them, carrying pain and a shrinking from pain, so that the music and the voices coming from the radios couldn’t possibly shut it out, for it was inside them.

Just as Lutie’s singing in the bar gave voice to a sorrow shared by her audience, so does her crying. Lutie’s voice, though suppressed at every turn, cannot be completely eliminated, and so it gets shunted to other outlets through which it erupts from time to time. On one occasion,

As Lutie climbed the stairs, she deliberately accentuated the clicking of the heels of her shoes on the treads because the sharp sound helped relieve the hard resentment she felt; it gave expression to the anger flooding through her.

By the end of the novel, Lutie’s irrepressible cry has found a way to erupt in a decisive way, if not in a way you’d expect.

The people in the novel who make life difficult for Lutie are not simply evil. We might at first be inclined to write off as a pure villain the “cellar crazy” super of Lutie’s building, who can’t conceal his lecherous desire for Lutie. But then we learn that he was so drained by the solitude of working as a night watchman that he decided to become a super in Harlem, “because that way there would be people around him all the time.” After serving in the Navy, he had returned to America to find that these were the only opportunities available to him. Society abandoned him. He was forced to spend so much time alone in buildings that he lost the ability to interact normally. So although we may despise the actions of the super and of other characters, we cannot go so far as to blame them and call it a day. Ultimately it is society, which exacerbates the impulses behind most of the evil actions in the novel, which bears the brunt of Petry’s critique.

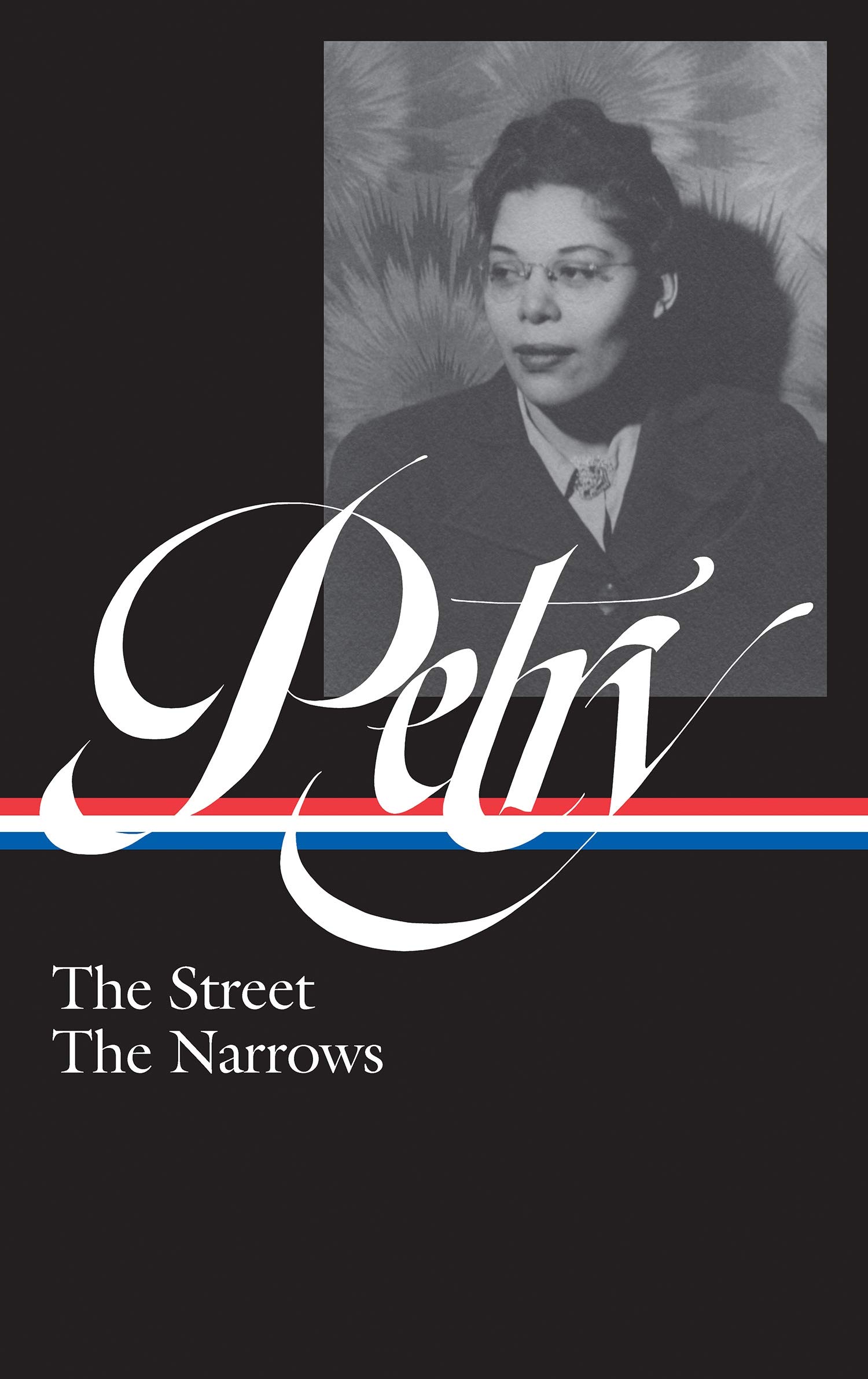

Petry is intent upon her target, which is to say, society. Petry isn’t pandering to the critics; she has a sincere message of social critique to which she humbles herself as a writer. In her 1950 essay “The Novel as Social Criticism” (included in the upcoming LOA volume Ann Petry: The Street, The Narrows), Petry refers to The Street explicitly as a novel of social criticism. She writes against the idea, popular in midcentury criticism, of art for art’s sake. To Petry’s thinking, art should exist not for its own sake but for the sake of people, and it would be disingenuous to pretend that the novel exists in a vacuum:

It seems to me that all truly great art is propaganda, whether it be the Sistine Chapel, or La Gioconda, Madame Bovary, or War and Peace. The novel, like all other forms of art, will always reflect the political, economic, and social structure of the period in which it was created.

Fiction, according to Petry, has a central role to play in critiquing society. It can help people to understand that the victims of oppression are actually human—even when they do bad things.

| COMING IN FEB. 2019 |

|

| Ann Petry: The Street, The Narrows |

I first encountered Ann Petry’s writing here as an intern at Library of America. While doing research for the website, I set off on the internet in search of a good blurb on Petry. It took me no time at all to find blurbs for well-known figures like Flannery O’Connor and David Foster Wallace, or for established critics like Pauline Kael. But finding something on Petry took a while. Although The Street was a runaway bestseller when it was first published, over the years Petry’s fame has waned. She has generally been neglected by both critics and readers. It has been standard practice to preface any treatment of Petry with an apology for her lack of literary status, and to undercut praise of her with comparison to writers such as Richard Wright, treating The Street as merely a female counterpart to his Native Son. Within this framework, Petry’s true merits go unrecognized.

A core part of Library of America’s mission is to call attention to writers like Petry, who have had an undeniable impact on American letters but who have been forgotten. Hopefully, the publication of the upcoming LOA volume will help amplify Petry’s voice, as well as Lutie’s.