As Summer 2018 winds down, we’ve asked our two summer interns to share something they learned during their time with Library of America. Below, S. Joyce-Farley, a junior at Smith College, describes discovering the novelist and short-story writer Nancy Hale (1908–1988).

“Miss Hale’s knowledge of the inner workings of her fellow-women’s minds is almost appalling.”

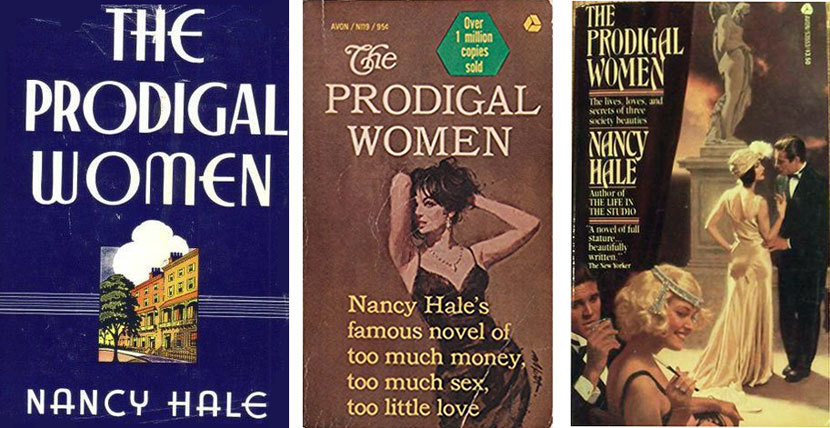

So said Orville Prescott in his 1942 New York Times review of The Prodigal Women, upon confronting a novel written by a thinking woman. The alien mechanics of women’s minds having been so precisely mapped out for him, he is unsettled. He goes on to write “Her entire book seems . . . to be a criticism of a life lived selfishly and pettily without faith or purpose or integrity of character.”

The Prodigal Women was Nancy Hale’s third novel and the best-selling book of her literary career. Born in Boston in 1908, Hale published her first story in the Boston Herald at the age of eleven, and continued to write and publish until her death in 1988. She ranks among The New Yorker’s most prolific authors, in addition to being the recipient of ten O. Henry Awards for her short stories. Her fiction primarily spans the landscapes of New England, New York City, and the South. Her subject matter is a clear reflection of her own experiences: in their depictions of growing up, of motherhood, of mental illness, and of belonging.

But absent from Hale’s writing is the sense of righteousness Prescott ascribes to it, so I can only wonder what wellspring of self-satisfaction he draws from to speak so confidently of faith, purpose, and integrity after reading The Prodigal Women. Coming across women characters whose complexity went beyond chaste industriousness, homemaking, or being variously entered and exited, he simply concludes that their stories are ones of moral instruction. Our culture tells us that flawed men are portraits of humanity; flawed women are lessons.

Hale wrote all about flawed women, and for them. Focused on domestic space in a world in which power is consolidated in the hands of men, her stories were, and remain, inherently subversive. But on the whole to label her work feminist is to ask it to bear the weight of a liberatory politics it cannot support. Radical change is not the impetus of her writing, and neither does her work particularly strive toward women’s solidarity across lines of race and class.

In “The Japanese Garden,” Hale explores the nexus between childhood, masculinity, race, and nationhood in wartime. In stories like “All Anybody” and “How Would You Like To Be Born,” she draws on her experience as a New Englander living in the South to describe variations of white consciousness that are thick with power, self-righteousness, fear, and complacency; they are illuminating portraits even as they reveal the racialized thinking of the time and place in which they were written. Hale didn’t shy away from selfishness or hatefulness; her stories have a unique way of making a home in the nasty.

I was introduced to Nancy Hale for the first time here at Library of America, back in June. I didn’t know who she was, so I asked around about her. Not even my grandmother (a retired English teacher and a member of not one, but several, book clubs) recognized the name. Confounded as I was by her obscurity, it was a gift to read her collections and track her publications across bound and bulging magazine archives and microfiche.

By the end of my first day at LOA I had fallen a little in love with Hale’s writing. All it took, really, was the first story, “Midsummer.”

The word “melodramatic” describes exaggerated emotions, sentimentality, the overly dramatic. It almost always refers to women’s writing. “Women,” who are weak, irrational, sappy, and not-worth-reading, to be filed under Chick Lit (or some variation of that name), so that everyone knows that if they must be read they certainly aren’t to be taken seriously.

That said, “Midsummer” is the melodramatic story of a teenage girl’s awakening. I say this with full, and somewhat vicious, intention.

The story is a snapshot of a sixteen-year-old Connecticut girl’s dalliance with Dan, her Irish riding instructor—are you rolling your eyes?—in which Hale examines Victoria’s dawning physical and existential urges with a serious consideration that the passions of teenage girls are rarely given. Dan serves far more as a tether for the intensity of Victoria’s desire than a romantic lead.

None of it was leading to anything. Nothing in the world seemed to be leading to anything. Victoria had no idea of making Dan run away with her, or of young dreams of happiness—she was conscious only that her relief was in him.

The days pass and Victoria remains in a torpid, overwrought state; our sense of this is heightened by the story’s strange gothic atmosphere and dreamy, feverish tone.

Victoria was sixteen, and sometimes . . . she thought she would go wild with the things that were happening insider her . . . [S]he could only sit around interminably in chairs on the lawn in the heat and quiet, beating with hate and awareness and bewilderment and violence, all incomprehensible to her and pulling her apart.

“Midsummer” read to me like a revelation. And, look, I’m a child of the twenty-first century. Women’s sexuality isn’t a shock or a secret. But the story is striking because of the immediacy and expansiveness of feeling with which Hale describes Victoria’s hormonal delirium. Rather than originating in him, Dan is simply where it all happens to fixate. Dan’s presence provides the story with a grounding framework—a summer fling—but his irrelevance is liberating.

Eighty-four years after it was published in The New Yorker, “Midsummer” is still a startling and evocative portrayal of adolescent desire. Hale has a knack for finding the alien planes of human feeling—those flashes of impulse or emotion that disrupt our expectations about young love, motherhood, or marriage. Her stories are often defined by emotional watershed moments: “The Bubble,” “A Curious Lapse,” and “On the Beach,” to name a few. As jarring—and often fleeting—as these epiphanies are, they resonate. Hale herself said, “Stories of mine that have made readers say, ‘Why! That’s just the way it is with me,’ seem, to my surprise, to be about what I should have thought most, most private, most personal to myself . . . I seem to do better by the world when I am acting for what is most inwardly myself.”

Hale’s closeness to that inward self, and the raw clarity with which she articulates it, is the defining strength of her writing. Like the work of many of her contemporaries, her fiction is propelled by a deep sense of dissatisfaction; she sees into the little uglinesses of life, the insufficiencies in ourselves and our relations, and how we grapple with them.

Hale is a writer for women who aren’t interested in being lessons. One who would rather sift through people’s accumulated desires and frustrations, and who looks at them in all their gritty, petty truth. She can help us understand the worlds we live in a little better—at least those of us not entirely confident in faith, or purpose, or integrity of character.

A collection of Nancy Hale’s short stories, selected and introduced by Lauren Groff, is currently scheduled for the fall 2019 season.

S. Joyce-Farley is a summer intern at Library of America. They are studying English and Sociology at Smith College.