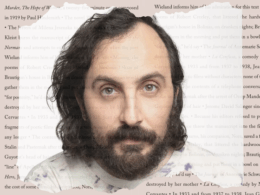

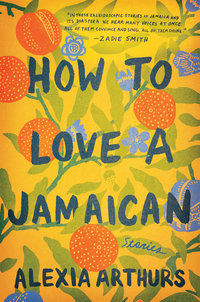

Our series of guest posts by contemporary writers returns with the following contribution by Alexia Arthurs, whose debut collection of short stories, How to Love a Jamaican, is published this week by Ballantine Books.

The eleven stories in How to Love a Jamaican explore the many facets of the Jamaican American immigrant experience, in settings that range from the island itself to midwestern U.S. university towns and the diaspora community in New York City. The book has already drawn noteworthy advance praise from other fiction writers: Ayana Mathis lauds it for a “an intimacy that will stay with you long after you’ve turned the last page,” and Zadie Smith calls it a “thrilling debut collection” in whose stories “we hear many voices at once: some cultivated, some simple, some wickedly funny, some deeply melancholic.”

Below, Arthurs reflects on a key influence on her debut, and positions her work in a fruitful dialogue with several other recent works of Caribbean American fiction.

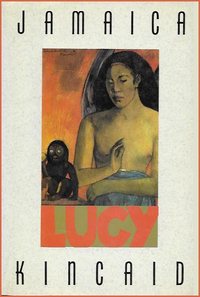

The first time I read Lucy by Jamaica Kincaid, during my early twenties, I respected it, but I don’t think I loved it, and by love I mean the way that people who read books adore books—as a testimony, aligning narratives with their world views, and the events of their lives.

The slim volume tells of nineteen-year-old Lucy, who leaves her family in the Caribbean to become an au pair for a wealthy white family in the United States. It interested me that so much of Lucy mirrored my life. I too had taken care of wealthy white people’s children—I had been an undocumented college student in New York, and childcare offered me the opportunity to pay my tuition out of pocket. Was my resistance because I recognized myself too clearly? It’s true that the narrator’s descriptions of a relative felt like a description of me: “On the last day I spent at home, my cousin—a girl I had known all my life, an unpleasant person even before her parents forced her to become a Seventh-Day Adventist—made a farewell present to me of her own Bible, and with it she made a little speech about God and goodness and blessings.” Later, I would mature, becoming more like Lucy, a more knowing daughter, with that intelligence that daughters have for straddling expectations and reality: “I said, ‘How are you?’ in a small, proper voice, the voice of a girl my mother had hoped I would be: clean, virginal, beyond reproach.”

Now, Lucy is a book I love passionately and completely. I have found it to be a lesson in Caribbean feminism—that navigation of doing and being and desiring without permission and in spite of hypermasculinity and misogyny. I’ve read and reread, and I marvel at how this book feels prophetic for who and how I would become because my first book, How to Love a Jamaican, feels to me to be in conversation with it. In my stories, there is a peripheral intimacy with whiteness, and an exploration of displacement for Jamaicans who emigrate. Also, my stories are interested in gender and sexuality for Caribbean people. When I was writing some of the stories, I had This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Díaz in mind. That book, for me, is interested in gender roles from a largely Dominican male point of view, and I wanted to represent the voices of Caribbean women. I had an imaginary title—This Is How You Win Her. But the loudest echo between my book and Jamaica Kincaid’s is familial relationships—mothering in particular. Lucy makes a comparison between her boss, Mariah, and her mother—“This was a way in which Mariah was superior to my mother, for my mother would never come to see that perhaps my needs were more important than her wishes.” I have this line in my book—“Caribbean mothers want to eat their daughters.” It’s a line of dialogue I borrowed from a friend, who is Caribbean as well.

One could argue that there is a preoccupation with maternal figures in Caribbean literature. I like to think that How to Love a Jamaican is in conversation with books like Lucy or Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid, Breath, Eyes, Memory by Edwidge Danticat, and The Star Side of Bird Hill by Naomi Jackson. I believe that this interest in mothers, mothering, and other maternal figures is partially due to the fact that Caribbean households tend to be woman-centric in that so much of the caring and other practical duties of living are women’s work. In this way, Lucy’s narration rings stirringly true:

My past was my mother; I could hear her voice, and she spoke to me not in English or the French patois that she sometimes spoke, or in any language that needed help from the tongue; she spoke to me in language anyone female could understand. And I was undeniably that—female.

Born and raised in Jamaica, Alexia Arthurs moved with her family to Brooklyn, New York, when she was twelve. A graduate of Hunter College and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Arthurs has been published in Granta, Vice, The Sewanee Review, and Virginia Quarterly Review. Her story “Bad Behavior,” which is included in How to Love a Jamaican, won the Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize for Fiction in 2017.