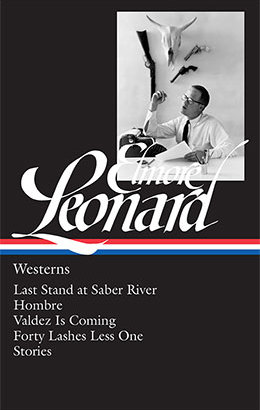

Released this spring by Library of America, Elmore Leonard: Westerns collects the crime fiction master’s work in the genre that made him as a writer and remained close to him for his entire career. For the LOA volume, editor Terrence Rafferty has selected the best of Leonard’s Western writing, which includes novels like Hombre and short stories like “Three-Ten to Yuma” that later became popular and well-regarded movies.

The author of The Thing Happens: Ten Years of Writing About the Movies, Terrence Rafferty has written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The New York Times. He has taught comparative literature at Cornell, film criticism at Columbia, and writing and American Studies at Princeton. For Library of America’s Moviegoer series, he wrote about the film adaptations of Carson McCullers’s Reflections in a Golden Eye, David Goodis’s Shoot the Piano Player, and Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw.

Library of America: Leonard published eight Western novels and thirty Western short stories in total. With such a large body of work to choose from, what criteria guided your selection in putting together the Library of America volume?

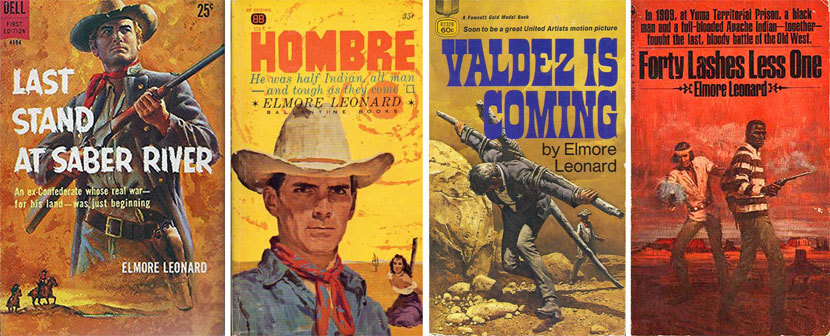

Terrence Rafferty: Picking the novels was surprisingly easy. Hombre and Valdez Is Coming were automatic. They’re classic Westerns, lean and tense. Leonard’s first three novels—The Bounty Hunters, The Law at Randado, and Escape from Five Shadows—are solidly entertaining, well-constructed genre books, much better than apprentice work, but his fourth, Last Stand at Saber River, feels richer and deeper, a real leap forward for him as a novelist. So that had to go in. Which left only his last two, Forty Lashes Plus One and Gunsights, both written after he’d begun to write other kinds of novels. It was a close call, but Forty Lashes is a little more inventive and surprising, so it won out.

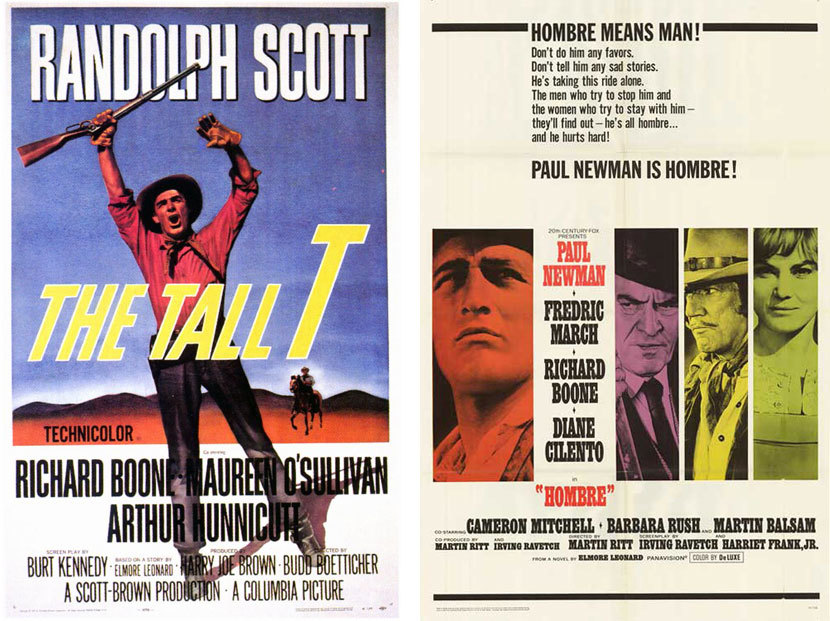

The stories were tougher, because there wasn’t room for more than eight or nine of them, and they’re pretty consistently strong. His very first published story, “Trail of the Apache,” had to be there, I thought, and “Three-Ten to Yuma,” which has been filmed twice (in 1957 and 2007), and “The Captives,” which was the basis for a terrific Budd Boetticher picture, The Tall T. The rest are just ones I especially like.

LOA: Two of these four novels, Valdez Is Coming and Forty Lashes Less One, feature nonwhite protagonists, while a third, Hombre, centers on a white outcast who was raised by Apaches. Were these racial elements remarked on at the time? Did Leonard ever address them, publicly or in correspondence?

Rafferty: Since all Leonard’s Western novels were published as paperback originals, practically nothing about them was remarked on at the time in newspapers or magazines, which paid no attention to genre fiction between soft covers. By the time the movies of Hombre and Valdez Is Coming were released, there had been a handful of Western films with non-white protagonists. (Or mixed-race heroes like the title character of Hondo, who had Apache blood and was played by, of all people, John Wayne.) What Leonard was doing was neither unprecedented nor particularly common, and I doubt he pondered it much. If a character’s race helped create a little extra conflict and make the story more interesting, he’d use it. That said, his portrayals of American Indians, African Americans, and Latinos were unusually stereotype-free for their time.

LOA: For his crime fiction Leonard regularly returned to two cities he knew well, Detroit and Miami, whereas his Westerns are all set in Arizona—a state he’d never visited when he began writing. How do we account for their air of verisimilitude?

Rafferty: I think an “air” of verisimilitude is about right. He got his information from history books, Western movies, and the pictorial magazine Arizona Highways, and that was about all he really needed. With Leonard, physical description of characters or landscape is never very important, anyway. His West is an idea of the West, an imaginary setting for the sort of drama he was drawn to—people trying to negotiate tricky, perilous situations, which were in long supply in the lawless (or nearly) Old West. He had the Western attitude: he understood, and sympathized with, the craftiness and hard-headedness required to survive on the frontier.

LOA: Leonard’s ear for contemporary American speech, as revealed through his masterly dialogue, is one of his most distinctive traits. How does the dialogue in his Westerns compare to its equivalent in his crime novels?

Rafferty: Well, Westerners are, by reputation, on the laconic side, so the dialogue is a bit less prominent than it would become in Leonard’s contemporary crime novels. It’s terse, honed—dialogue for Gary Cooper or Randolph Scott, rather than for, say, John Travolta or Samuel L. Jackson. Is it good? Yup.

LOA: A handful of notable movies, such as The Tall T and 3:10 to Yuma, came out of the novels and stories in this collection. Are people who only know the movies likely to find things in Leonard’s originals that aren’t in the Hollywood versions?

Rafferty: Until late in his career, Leonard was reliably cranky about the movie adaptations of his work. He thought Hollywood “screwed up” his simple stories, added all sorts of extraneous stuff that he’d known well enough to leave out.

LOA: After spending time in Leonard’s Old West, it’s interesting to reconsider the contemporary novels and stories he wrote about the Kentucky lawman Raylan Givens late in his career. Is it possible the Raylan stories were his surreptitious way of revisiting the genre he loved, long after it had fallen out of commercial favor?

Rafferty: It’s undeniable that the Raylan stories and novels are essentially Westerns in modern(ish) dress. He’s a marshal, like an Old West lawman, and he’s got the requisite man’s-gotta-do-what-a-man’s-gotta-do attitude. Actually, there are quite a few of Leonard’s later novels that play like Westerns: his historical novels Cuba Libre and The Hot Kid certainly fall into that category. (At one point, I seriously considered trying to smuggle one or the other into this volume.)

And he did call one of his urban crime novels City Primeval: High Noon in Detroit, which sort of gives the game away. All his books, Western or not, are about dispensing justice in some form—legally or extra-legally, but it’s invariably a complicated, twisty process. His favorite sort of hero, right from the beginning of his writing career, was a quiet hombre whom the bad guys fatally underestimate. Bob Valdez and the other protagonists of the novels and stories in this book are all ancestors of Marshal Givens. In a sense, Elmore Leonard never really stopped writing Westerns.