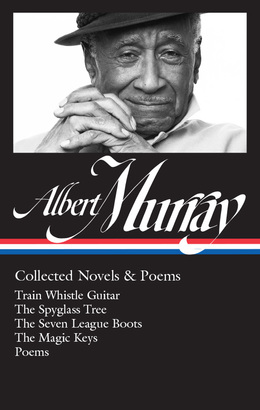

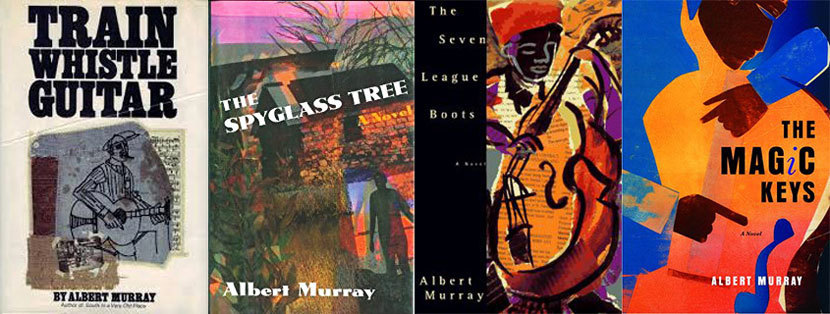

Released in February of this year, Library of America’s Albert Murray: Collected Novels & Poems brings together, for the first time in one volume, Murray’s complete Scooter novels, the semi-autobiographical quartet originally published between 1974 and 2005—Train Whistle Guitar, The Spyglass Tree, The Seven League Boots, and The Magic Keys—along with a selection of Murray’s poetry and two short stories from opposite ends of his fiction-writing career.

Like its predecessor, Albert Murray: Collected Essays & Memoirs (2016), the new collection is co-edited by Paul Devlin, Assistant Professor of English at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University as well as a documentarian, critic, scholar, and a member of Library of America’s Board of Advisors.

Devlin is also the editor of Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues (2016) and Rifftide: The Life and Opinions of Papa Jo Jones, as told to Albert Murray (2011), which was a finalist for the Jazz Journalists Association Book Award. Via email, he shared some thoughts on the new book with Library of America.

Library of America: This edition of Murray’s complete novels (and most of his poetry) is a companion volume to Library of America’s Collected Essays & Memoirs, which was published in fall 2016. What are some of the continuities between his nonfiction and his more openly imaginative writing—and what might we discover about Murray in his novels that may not be as apparent in his essays and criticism?

Paul Devlin: The continuity is found in the musicality of his prose (rhythm, cadence, lyricism) and in his erudition (expressed differently in his nonfiction). One difference is that in his fiction his jazz-based method of composition is more apparent. In the 1940s Murray was inspired by Thomas Mann’s use of the structure of European art music in his fiction. Murray then applied this approach to the music he grew up with and developed fiction structured on jazz and the blues. The form and the content become inseparable as jazz and the blues, for Murray, became a metaphor for contemporary life.

Another difference is in his humor. There is also a gentler, less pugilistic, and more boisterous humor, as compared to the razor wit employed so effectively in his early essays. It’s less “wow, he really owned Moynihan” (and he does, of course, dismantle The Moynihan Report in The Omni-Americans) and more of a sparkling, buoyant, Whitmanian or Rabelaisian laughter that seems to echo through the fiction. I think there is an analogy to be made between Murray’s novels and Richard Howard’s description of Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma in his afterword to his 1999 translation of it: “a miracle of gusto, brio, élan, verve, and panache.”

LOA: Aside from how Murray’s fiction differs from his non-fiction, how does it differ from the fiction of his contemporaries, such as Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, Saul Bellow, or John Cheever?

Devlin: Aside from a general concern with representing life in the twentieth century, in almost every way imaginable. Haha. There is nothing quite like Murray’s fiction, as far as I know. Murray emphasizes the heroism in the African American tradition more than any other writer. His fiction received overwhelmingly favorable attention over the years, but to paraphrase several critics: “this is great, but what is it?” Is it a novel or is it a prose poem? John Leonard wrote of The Magic Keys that it is “less kiss-kiss bang-bang . . . than elegy, reverie, memory book, and musical score, as well as a thank-you note to the entire sustaining community of black America.” Leonard was a prolific critic, a reader of almost unparalleled experience, yet he found Murray’s work difficult to classify. It defies expectations of plot and genre. Murray’s ambition to achieve the literary equivalent of Duke Ellington’s orchestration integrates elements of the Bildungsroman, the picaresque, the fairy-tale, and the lyricism of the orchestrated blues statement. The novel is Murray’s form, but within that form, he is beyond category.

There was a fine article a few years ago called “Reading with the Grain: A New World in Literary Criticism” by Timothy Bewes. Bewes writes that “reading with the grain” is “a reading that is tied to the novel form, that recognizes the novel as part of its own formation, and that resolves to read, henceforth, alongside the novel.” I think Murray’s novels are ideal for this approach and may reward that style of reading—open to the text’s possibilities and internal dynamism (not unlike what Rita Felski advocates in The Limits of Critique.)

LOA: How about Murray’s poetry?

Devlin: Murray’s poetry is diverse in style and content—some poems expand on points he made in various essays and some grow out of his fiction. Of course, some poems have no obvious connection to either. There are eleven poems published for the first time in this volume. Most of the poems were included in his 2001 book Conjugations and Reiterations. The title says it all—it signals a sort of poeticizing of his worldview, the blues metaphor, and his previous work. I don’t think he thought of himself as a capital-p poet, but he knew the Anglo-American modernist tradition inside out. He must have had thousands of lines memorized (Eliot, Yeats, Auden, Millay, and many more). In some cases he offers a poetic riff on a theme he’s explored elsewhere in other genres. There is a poem critiquing Sigmund Freud, for instance. He also “does the police in different voices,” one might say. He does a Wallace Stevens voice, for instance, and a T. S. Eliot voice, and a Faulkner voice. It’s somewhere between (and may slip to and from) parody and homage—a momentary mask or lens. Of course, there is more to it than that. Murray’s seventy years as a careful reader of Faulkner, for instance, went into his profound meditation on his work and themes. I think he had a lot of fun preparing the collection. He loved to read portions of it, especially prior to its publication.

LOA: What is the relationship between the poetry and the fiction?

Devlin: In a sense he distilled or abstracted his novels as a suite of twelve bar blues stanzas (five of which are published here for the first time). In the LOA volume they’re in a section called “Aubades: Epic Exits and Other Twelve Bar Riffs.” They are very much songs of the morning and reflect the sunlit mood of his fiction.

Incidentally, his use of the twelve bar blues stanza should be understood as that of a blues singer from eighty years ago—he is not appropriating a form, but instead employing a form that had been part of his consciousness for his entire life. Murray grew up in Mobile, Alabama listening to blues guitarists and singers of Leadbelly’s generation, whom he immortalized in the dashing character Luzana Cholly in Train Whistle Guitar. Murray was born in the same decade as Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, and Howlin’ Wolf. His career took a different path, but he was just as much an heir to the blues tradition. . .

LOA: Does music inform the other poems as well?

Devlin: There is a definite musicality to many of the poems that are not twelve bar blues stanzas per se. Last spring saxophonist David Murray (no relation) and I were talking about this and we decided that I should try to read them with his musical accompaniment. We did this as part of a tribute to Albert Murray at Harvard, at which we were already lined up to do other things, and then at another venue in New York in the same week. So, I read Murray’s poems over David’s and his band’s renditions of various classics associated with the artist in question—I read Murray’s poem about Duke Ellington over “Take the A Train,” his poem about Count Basie over “One O’Clock Jump,” and his poem about Thelonious Monk over “Bright Mississippi.” The words of each poem seemed to interlock with those tunes. In our rehearsals we tried out a variety of numbers before we figured out the right ones, which seemed to really gel—that is to say the words seemed to fit with the melodies in a way that makes me think Murray had been thinking about these tunes in some manner while composing the poems. I’m not any great performer of poetry or anything—we just had fun with it. It was in a spirit of play that I think Murray would have appreciated.

LOA: The Scooter novels—Train Whistle Guitar, The Spyglass Tree, The Seven League Boots, and The Magic Keys—are grounded in a rich sense of place: New York, Los Angeles, but especially Mobile, Alabama, in Train Whistle Guitar, and Macon County in central Alabama, in The Spyglass Tree. Could you talk a bit about how Scooter, and Murray himself, relate to the Alabama setting?

Devlin: Murray loved to talk about Mobile, where he grew up, and Tuskegee (Institute and town), where he went to college, later taught, and served as a training officer for the Tuskegee Airmen. Thanks to Murray, the African American sections of north Mobile (Magazine Point and Plateau) are now on the map of American literature, like Henry James’s Manhattan, Zora Neale Hurston’s Eatonville, Philip Roth’s Newark, or Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. Magazine Point’s idiom, music, rhetorical brilliance, sawmill whistles and train whistles—and its violence and class conflict—all that was good and bad about it—is now part of Gasoline Point in the novel. It’s a world few would have guessed existed—rescued from oblivion by Murray’s memory and literary craft—and now forever in print. (Incidentally, see the final question below for a discussion of a map of Gasoline Point and Plateau, the adjacent neighborhood.)

LOA: This locality has been in the news in recent weeks and months for two different yet related reasons: the probable discovery of the slave ship Clotilda, the last to enter the United States, and the publication this month of Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”—her long-lost interviews with Cudjo Lewis, the last survivor of the ship. Does Murray write about any of this local history?

Devlin: Yes. Murray knew Cudjo Lewis. In Train Whistle Guitar there is a character closely based on him. Murray also writes of the Clotilda (it’s even featured on the map—see final question). In Murray’s youth the hull was still visible. (The ship was scuttled in 1860 and the hull was visible in the 1920s.) In conversation with me Murray remembered meeting Hurston in her visits to the area. At one point, so he recalled, she was collecting folklore from the workers who were building the Cochrane Bridge across the Mobile River. Murray was around ten or eleven, and had a little job, alongside other kids, carrying drinking water for the workmen. Hurston would chat and joke with the kids. He had fond memories of her. It is extraordinary that Murray’s books, Hurston’s book, and the ship itself all reemerged in the same season, winter/spring 2018. (While reports of the discovery appear to have been premature, they brought a lot of attention to the story, which is true, and connected with Murray’s story.*)

LOA: Murray’s novels exhibit a profound engagement with literary modernism—with Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner, and above all the achievement of his great friend and correspondent Ralph Ellison. What is your sense of how Murray assimilated these influences, and perhaps even resisted them, too, in making the modernist tradition his own?

Devlin: Let’s start with Ellison. Engagement is a better word than influence, I think. They were great friends who often shared ideas and interests, as their widely-admired letter-exchange Trading Twelves demonstrates, but Murray had a different angle of vision, and consequently, a different conception of the blues (farce for Murray; near-tragedy/near-comedy for Ellison). Murray’s fiction seems determined to counterstate Invisible Man. Murray felt that Ellison did not create a protagonist who was as smart and savvy as Ellison himself was. He also criticized James Baldwin for this (and James Joyce as well—at least in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Murray’s ambition was to create a protagonist who had the erudition, savoir faire, common sense, and all round hipness that Murray himself had. But he creates an elaborate and largely affectionate portrait of an Ellison-like character (“Taft Edison”) in The Magic Keys. He also has an affectionate portrait of James Baldwin-like “Danny Dennison” in The Seven League Boots. Murray said somewhere that his zeal to critique Baldwin (in a famous essay in Essays & Memoirs), whom he taught to swim in 1950 in France, helped light the fire of his career in the ’60s.

But back to his jazz-like inversion of Ellison’s approach—I gave a paper on this at a symposium on Murray at Columbia University a few years ago, and it ended up quoted in the LA Review of Books: “Paul Devlin [. . . ] proposed an interesting theory about the ease with which Scooter moves through the world. If, as John S. Wright has suggested, the problems facing Ellison’s Invisible Man are those of the innocent hero of a bildungsroman who finds himself in a picaresque novel, then Scooter is the picaresque hero . . . with the great good fortune to inhabit a bildungsroman.”

As for the rest—Murray was a modernist writer. His wide reading on myth and ritual (mostly out of the Cambridge School) informs his work. He did his master’s thesis (1948) on symbols of sterility and fertility in Eliot and Hemingway. He not only knew the tradition as an artist but was a scholar of it as well. Murray’s riffs on Joyce and Proust are like Duke Ellington’s riffs on Debussy and Grainger. Readers of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man will recognize the evolution of the narrator’s consciousness from childhood to young adulthood. Faulkner’s influence can be glimpsed in The Spyglass Tree, while Hemingway seems to be the genius loci of the Paris chapters of The Seven League Boots. Allusions to Edna St. Vincent Millay bracket the protagonist’s moves to and from Greenwich Village. Modernism becomes part of the structure as well as the content.

LOA: The Note on the Text in this volume indicates that Train Whistle Guitar and The Spyglass Tree are both derived from a single large “ur-novel” Murray had begun writing as early as the late 1940s. What do we know about how the two finished books differ from that original project?

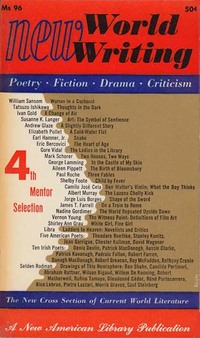

Devlin: Almost everything that’s known about the ur-novel comes from Ellison’s long letter to Murray of February 4, 1952 (Trading Twelves, 27–31). There are also undated sections of chapters and fragments in the archive. Our best idea of what the ur-novel must have been like comes from “The Luzana Cholly Kick,” a section of a somewhat later version published in New World Writing 4 in 1953, and reprinted in the appendix to this volume. It corresponds roughly to an early chapter in the 1974 text of Train Whistle Guitar (also in this volume). It’s close enough to the published (and successful) version to remove any doubts about the quality of Murray’s writing in the ’50s. Incidentally, Murray wouldn’t see another excerpt published until 1969. “The Luzana Cholly Kick” itself wouldn’t be reprinted until 1966.

LOA: That original manuscript met with incomprehension and even outright hostility when Murray showed it to a mainstream publisher in the mid–1950s. What elements in Murray’s fiction would you guess prompted that reaction?

Devlin: Well, it was rejected by several publishers in the 1950s and ’60s. A long anonymous reader’s report states the perceived problem outright: it says (and I’m paraphrasing) “we don’t care about books featuring positive, educated black characters—you can write about black people but you must be sure to have white racists oppressing them in brutal ways—we can sell that, maybe.” It’s incredibly obnoxious. But I’m glad Murray saved it! It’s a valuable artifact of a discredited mode of thinking about the literary marketplace. Many people would have been tempted to burn it or throw it away—or perhaps some would have conformed to its narrow vision. Murray refused to compromise his artistic integrity. And his persistence paid off.

Even when “The Luzana Cholly Kick” started to be anthologized in the ’60s and ’70s—and in some major anthologies at that, including The Norton Introduction to Literature—the gatekeepers on high just weren’t interested in more where that came from. The enormous impact and publicity of Murray’s first book, The Omni-Americans, didn’t even clear the way for his fiction. It was the success of Murray’s second book, South to a Very Old Place (1971), that resulted in an offer of a two-book contract from McGraw Hill, and the novel Train Whistle Guitar was one of those books. Joyce Johnson was the editor with the vision to finally accept it for publication.

But if not for Arabel Porter of New World Writing, who selected “The Luzana Cholly Kick” for publication in 1953, the trajectory of Murray’s career might have been very different. She saw something that her peers in the publishing world missed by a mile. Inclusion in the prestigious volume boosted Murray’s confidence. Had he not been able to place an excerpt anywhere, well, who knows. Maybe he wouldn’t have stuck with it. And thank goodness Porter and New World Writing saved every scrap of paper, including her opinions of the manuscript and her justification for publishing the excerpt, which were circulated in-house among her colleagues (and quoted in the Note on the Text in this volume). The New World Writing archive is in the Beinecke Library at Yale. The staff there was very kind and helpful to me when I was on the case of this special moment in literary history.

Here’s a funny thing that just occurred to me: Murray’s fiction required two women to bring it to light, while several prominent male editors of the 1950s–60s passed on it.

LOA: And in his fiction, it is two women, two teachers, who are so crucial to the protagonist’s development: Lexine Metcalf and Hortense Hightower. Why are these two characters so important to Scooter, and to the saga as a whole?

Devlin: Lexine Metcalf is Scooter’s elementary school teacher who expands his conception of the world. Hortense Hightower is a blues diva he meets in college. Through her he acquires a comprehensive education in the history of jazz and the blues (which he already knew a lot about from Mobile, prior to meeting her). Also through Hightower he gets caught up in a racial conflagration that enables him to demonstrate his integrity. Hightower rewards him with a bass fiddle and arranges for him to meet a famed bandleader who gives him a job, thus bridging the action from the second to the third novel. Murray says somewhere that they function like fairy godmothers.

There are several other important women in the books, but one of the most three-dimensional, in my opinion, is Gaynelle Whitlow, who appears in The Seven League Boots. In Chapter 35 she introduces some wry skepticism at a moment when it’s very much needed.

LOA: As this volume was in preparation, you explored the northern sections of Mobile, Alabama, that Murray fictionalizes as “Gasoline Point” in the Scooter novels. How much remains of the neighborhood Murray knew growing up?

Devlin: The house in which he grew up was in a neighborhood that was re-zoned for industrial use at some point between 1940 and 1969. He writes about it in South to a Very Old Place. But the residential areas surrounding it still have the same look that they would have had in the ’20s and ’30s—narrow streets, shotgun houses (some raised above ground level), omnipresent trains on the margins of the neighborhood. I had been there several times, but in my most recent visit I was thinking in terms of how the places relate to Murray’s map—spatially, historically, and so on.

While inventorying Murray’s apartment in 2015–16 I discovered a rough draft of a map, drawn by Murray in pencil, of the area in which Train Whistle Guitar takes place, which is the northern part of Mobile, where he grew up. Perhaps he had been thinking of the well-known Yoknapatawpha map included in Malcolm Cowley’s landmark Portable Faulkner volume. Anyway, the map was redrawn stylishly by Library of America’s Donna Brown and included on the endpapers of Collected Novels and Poems. I consulted and advised about various aspects of the map. I think it’s a really nifty addition to the volume and I’m so pleased by its inclusion. While Donna and I were working on it and comparing the places on Murray’s map with their positions in the published text (as his map conforms to a somewhat earlier version), I was able to get a street-level sense of it. Of course, we used Google Maps as well to check distances and dimensions. Murray was aiming for near-but-not-total-verisimilitude.. But as he writes, the place is more of a location in time than an intersection on a map:

The Official name of that place (which is perhaps even more of a location in time than an intersection on a map) was Gasoline Point, Alabama, because that was what our post office address was, and it was also the name on the L & N timetable and the road map. But once upon a time it was also the briarpatch, which is why my nickname was then Scooter, and is also why the chinaberry tree (that was ever as tall as any fairy tale beanstalk) was, among other things, my spyglass tree.

*For several decades, Clotilde was the accepted spelling for the last ship on record to have transported enslaved Africans to the United States, and was the spelling Albert Murray used. Clotilda seems to have become standard after 2000.